Since February 2025, the United States has undertaken a rolling process of resetting tariffs, driving them up to the highest levels since the 1930s. In this blog, we project the impacts of the US tariffs in effect as of September 11, 2025. We find that, if left in place over the coming decade, these tariffs would result in less US economic output, higher US prices, and lower American wages than if they had not been adopted.

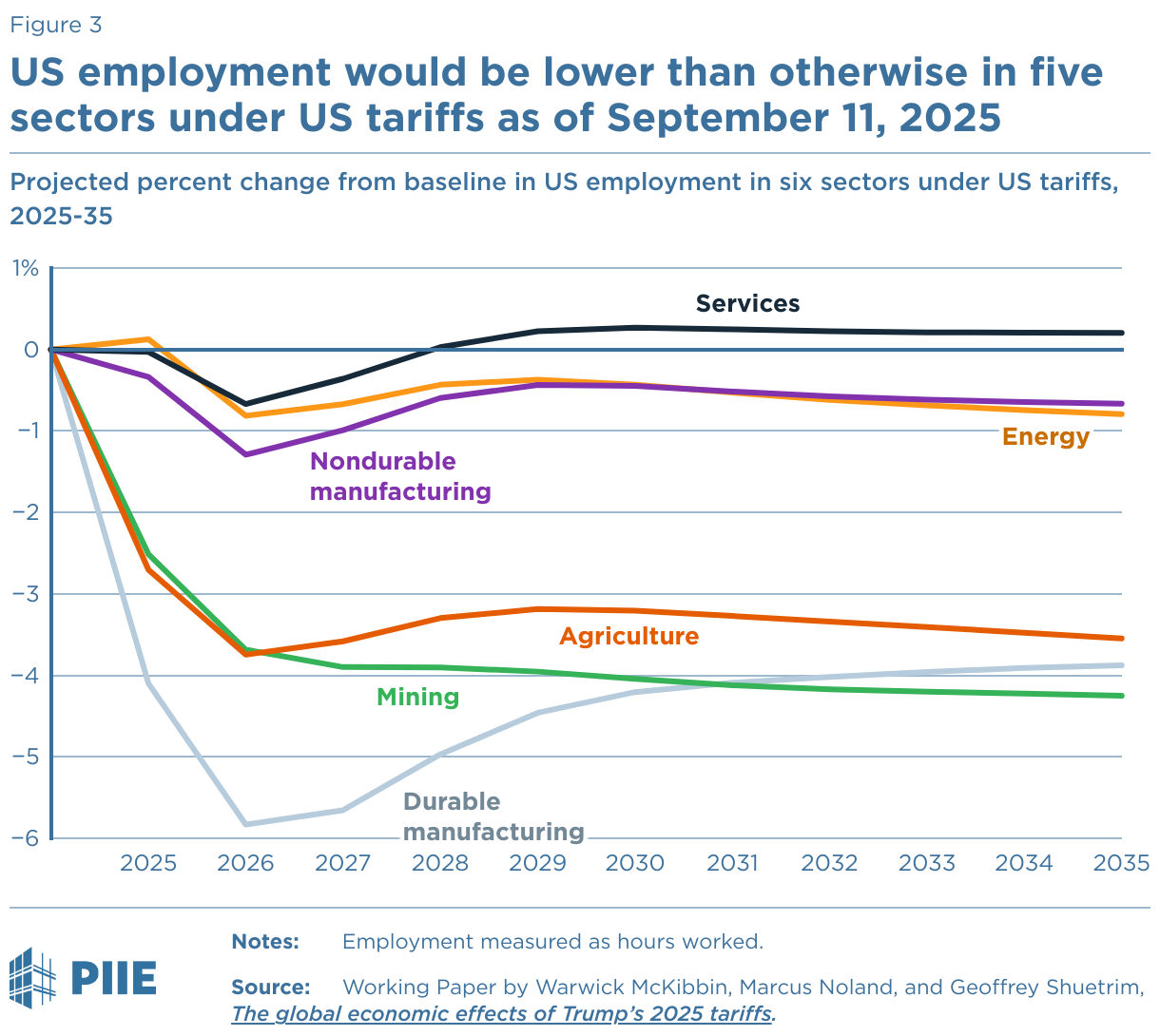

US employment, measured as hours worked, would decline in sectors most exposed to trade, with the biggest drops in durable goods manufacturing, mining, and agriculture, our work shows. The effect on manufacturing employment also reflects a slowdown in investment in the US economy due to the tariff increases.

This blog builds on our June 2025 PIIE Working Paper, “The global effects of Trump’s 2025 tariffs,” in which we used the G-Cubed global economic model to examine President Donald Trump’s so-called Liberation Day tariffs announced on April 2 and the changes to the tariffs made through May 10, 2025. We looked at the economic results of the US tariffs and trading partners’ retaliatory policies under several scenarios. Because US tariffs have changed so much since then, we conducted this new evaluation of those in place as of September 11, 2025.

For the September update, we again used the G-Cubed model to generate baseline projections for the US and global economies for the coming years if the tariffs were not adopted. We then projected the tariffs’ effects, measured as deviations from that baseline. A complete set of the updated macroeconomic and sectoral results for all economies in the model is available at this online dashboard. The dashboard also compares the September results with those in June under two scenarios—one assuming high US tariffs and the other assuming lower tariffs.

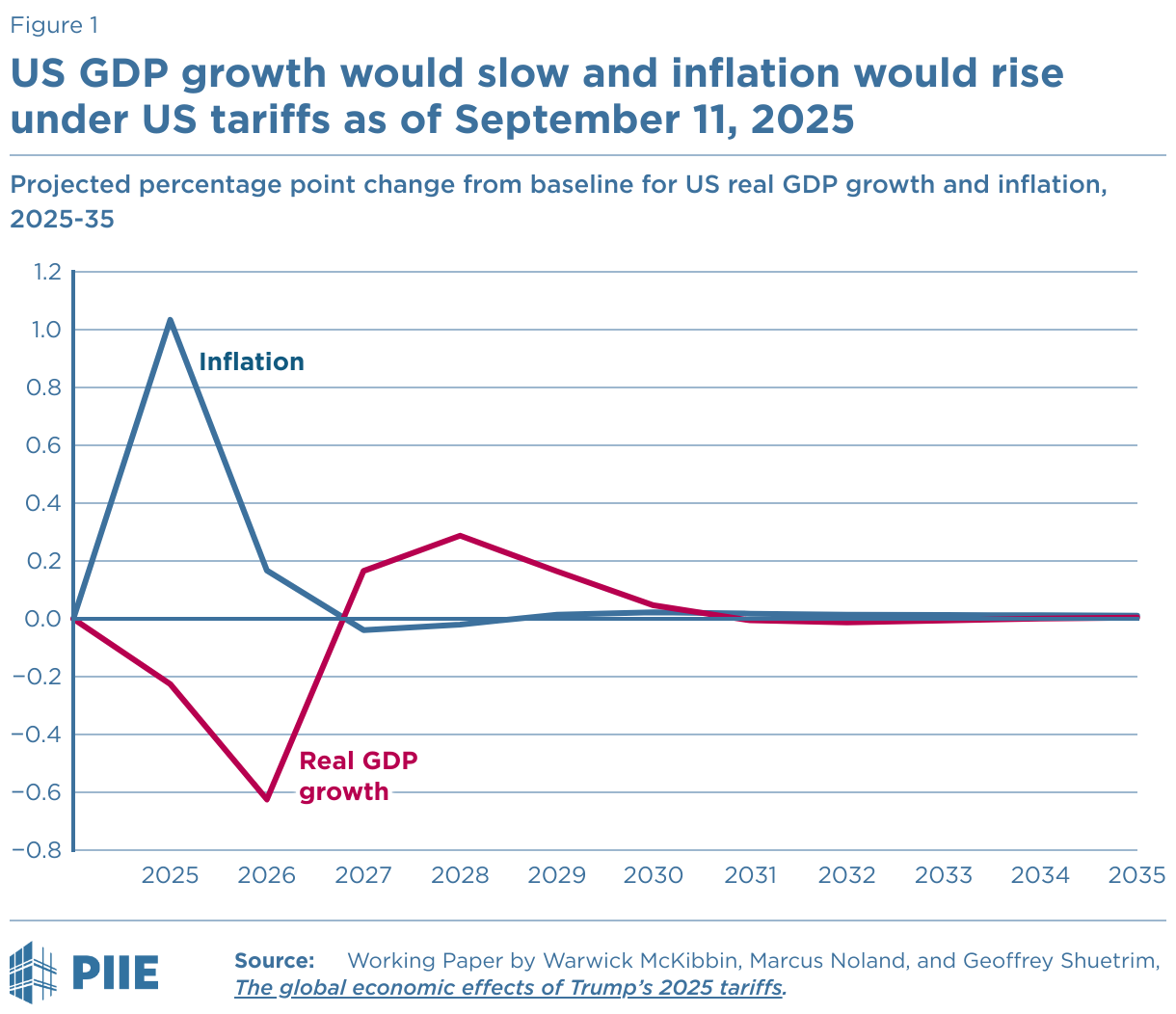

Figure 1 illustrates the drop in the US GDP growth rate and rise in US inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, from baseline. Inflation increases because the prices of imported goods rise. This translates into more expensive goods for consumers and higher costs for intermediate goods for US companies. GDP growth slows because import costs rise, the incomes of US households and firms fall, and foreign demand for US exports declines.

The tariffs reduce the US growth rate by 0.23 percentage point from baseline in 2025 and by 0.62 percentage point in 2026. Inflation rises 1 percentage point higher than baseline for the year from September 11, 2025. Inflation declines over time back to the baseline rate as the US Federal Reserve acts to balance the inflation surge with the initial growth slowdown. Although the inflation increase is temporary, the US price level remains higher thereafter than it would have been without the tariffs.

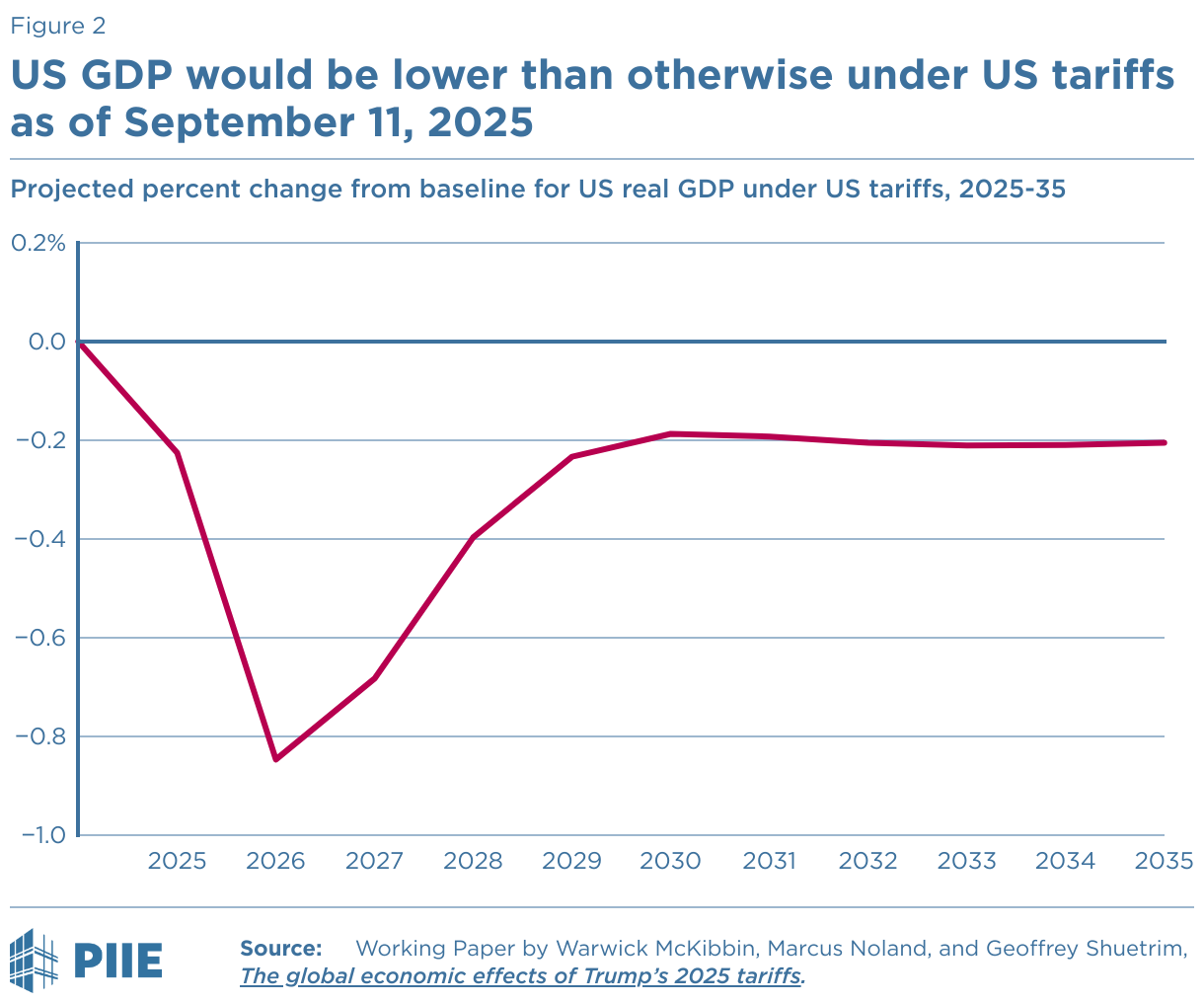

Figure 2 shows that the level of US real GDP in each year relative to the baseline due to the tariffs through the coming decade.

These tariffs alone are not sufficient to cause a US recession. But the US economy would contract if the tariffs were combined with the mass deportation of unauthorized immigrant workers and the US Federal Reserve’s loss of political independence, according to our September 2024 paper, “The international economic implications of a second Trump presidency.” The deportations and change in Fed policymaking would be much larger shocks to the US economy. We are updating the 2024 paper to reflect the recent US Congressional Budget Office projection of significantly reduced US population growth in 2025 because of increased deportations and reduced net immigration.

Figure 3 shows the employment effects in each of six sectors of the US economy. Note that employment declines most in durable goods manufacturing, mining, and agriculture, similar to the outcome in our June 2025 paper. These are the sectors most exposed to a decline in US exports caused by relative price shifts. The drop in durable manufacturing employment also reflects the slowdown of investment in the US economy because the tariffs reduce the return to capital in the most affected sectors and in foreign countries impacted by the tariffs. Total employment is assumed to return to baseline eventually, but with a permanent structural shift from the most trade-exposed sectors of manufacturing, mining, and agriculture to the service sector at lower real wages for all workers.

Comparing our US findings in September with those in June, we see the new results are closer to those in our June scenario that assumed high US tariffs than in the scenario assuming lower tariffs. More generally, the updated impacts on particular economies and sectors vary by more than in the previous exercise, due both to differences in the tariff rates applied and changes in relative tariffs applied across sectors and countries. To illustrate, the updated results show bigger negative impacts for Brazil and India because the US tariffs on them in September were larger than in June and larger in effective terms relative to Mexico and Canada. In the latter two economies, considerable trade remains tariff-exempt, particularly with respect to the sectors compliant with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

US tariffs are likely to continue changing, given the apparent use of tariffs as a foreign policy tool and in a misguided attempt to reduce the US trade deficit. The modeling framework used in this update finds that the trade balance responds more to shifts in national savings and investment than to changes in tariffs. This update considers only the effects of changes in tariffs and not the impact of the widening of the US fiscal deficit. The larger federal budget deficit projected to result from legislation enacted in July is likely to reduce US national savings and be financed by capital inflows from foreigners, which will worsen the US trade deficit.

Data Disclosure

This publication does not include a replication package.