When moving from one job to another, getting a salary bump is a key motivator. Yet salary alone tells only part of the story when it comes to job satisfaction. A highly stressful position, for example—or a crushingly mundane one—might be miserable no matter how high the pay.

Research from Chicago Booth’s Anders Humlum, University of Copenhagen’s Mette Rasmussen, and University of Chicago’s Evan K. Rose examines how workers weigh their paychecks against so-called nonwage amenities, which include factors such as lower stress levels, shorter commute times, and more flexibility. Using both survey and administrative records data, the researchers find that switching jobs often comes with substantial trade-offs between wages and amenities. These trade-offs have implications for our understanding of inequality in the labor market.

The research draws on data from Denmark, where national data provider Statistics Denmark surveyed more than 20,000 workers across approximately 7,000 companies in mid-2024. Respondents were aged 30–60, were currently employed, and had changed jobs at least once within the past three years. Survey responses were linked to administrative labor-market records to ensure accuracy.

Respondents were asked to evaluate their current and previous jobs based on wages and amenities. Topics included differences in starting pay between their new and old job, commute times, work-from-home frequency, opinions of the societal benefit of the jobs, and the jobs’ physical demands. The survey also asked about benefits such as vacation time and pension plans.

Respondents also indicated what salary they would accept to take their old jobs back and—to account for the role of personal preference in amenity value—what salary a typical worker with their skills would accept.

Balancing perks and paychecks

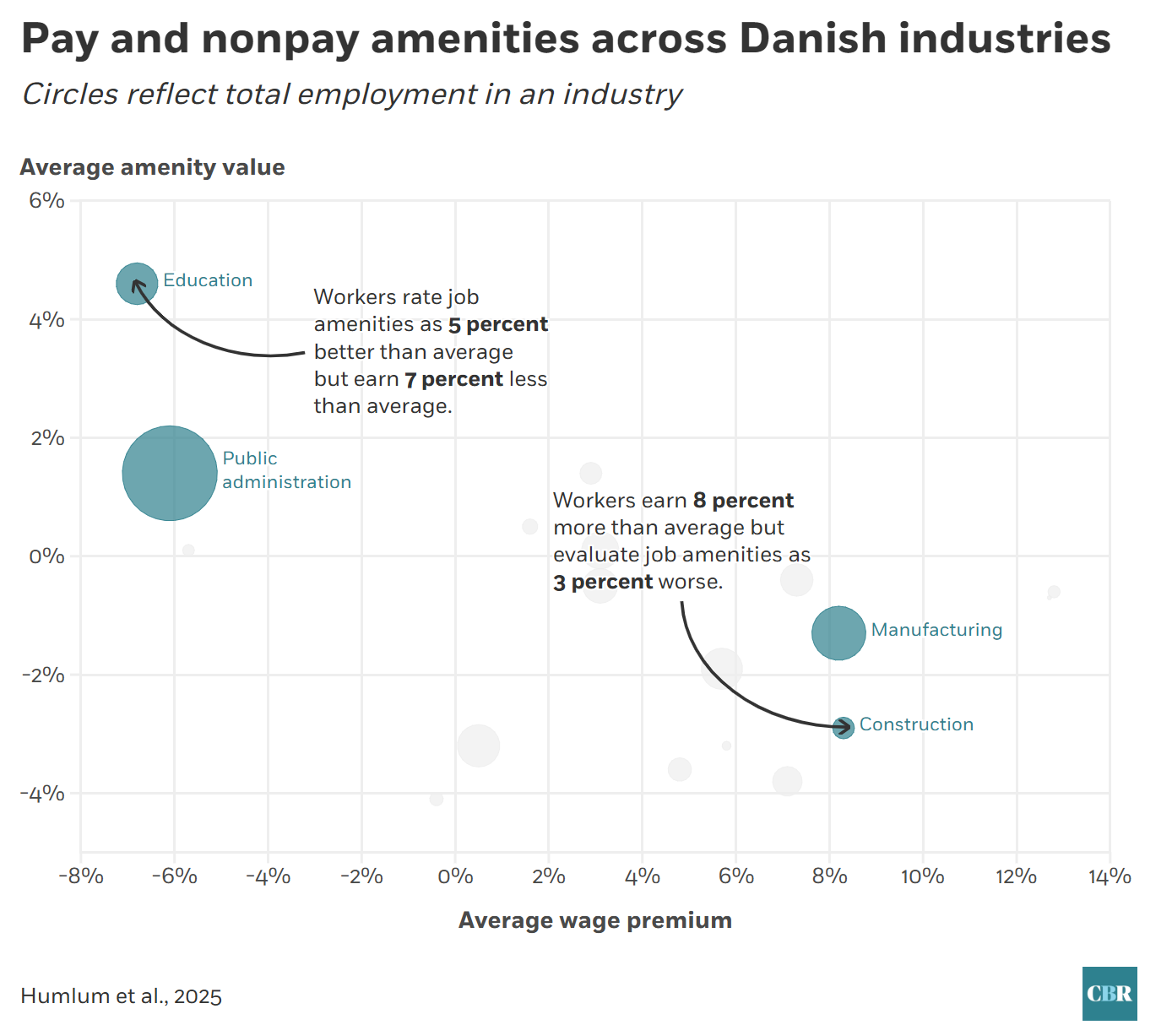

1. Education and public administration sectors, known to be family friendly and flexible, offer relatively better nonwage amenities, but also tend to be lower paying, the research finds. Lower amenity sectors such as construction and manufacturing tend to offer higher pay.

2. Overall, industries that pay relatively more often come with worse working conditions—although the pay gain outweighs the drop in amenities.

Using these data, the researchers could distinguish between firm-wide effects, which represent company qualities that apply to all employees (average pay, benefits, flexibility) and match effects, which indicate how well a job matches a unique worker’s skills and preferences.

The researchers find that, on average, workers at higher-paying companies reported worse overall amenities than those at lower-paying ones. High-salaried workers did report more flexibility, better perks, and less physically intensive jobs. However, their jobs also came with more stress, less job security, and a feeling that they were not adding any benefit to society.

Think of a company such as Google, Humlum says. “Yes, they may offer lots of perks, such as free food and other rewards,” he notes. “But the stress levels and pressures are also probably very high.” It’s a trade-off that may not always be apparent when job hunting, but can make a real difference once you’re on the job.

On average, the researchers find, a 10 percent wage increase came with a 5 percent decline in amenity value, with the bulk of that coming from match effects between workers and their companies.

Overall, more than half of the advantage of high wages is offset by worse amenities, according to the study. So while it may seem there is a huge variation in job quality across companies and industries when looking solely at wages, it’s only half as much as it appears when considering nonpay factors. This insight can make a substantial difference in how we view real job inequality.

Humlum, Rasmussen, and Rose find that average amenity effects also varied widely by industry. Amenities were ranked highest among workers in the education sector, dropping lower in sectors such as finance, insurance, and health. The lowest amenities were in hospitality and food services. “Some industries do offer both low amenities and pay,” Humlum says. “However, the overarching pattern in the labor market is that moving to better pay entails nonwage amenity trade-offs.”

Women were more likely to gravitate toward companies offering better nonwage amenities, particularly flexibility, family-friendly policies, and supportive environments. A 10 percent wage increase for women was tied to a smaller reduction in amenity value (4 percent) compared with men (7 percent). Overall, considering the value of amenities reduces the gender gap created by pay disparities between companies by 35 percent, the researchers find.

While weaker amenities can make high-paying jobs less valuable to workers, the researchers note, they are “not nearly enough to fully offset the benefits of higher pay.” Amenities should be seriously considered in employer packages, and they also have a real effect on how we should look at job inequality. But, for workers across the board, money may still talk the loudest.

click here to read more