Key messages

An increasing number of consumers rely on digital payments to transfer money and to buy goods and services. Between 2021 and 2024, the percentage of individuals who made or received a digital payment in developing economies increased from 55% to 62%, and it is 96% across OECD countries.

A significant percentage of consumers using digital payments do not display basic digital financial literacy. In 2023, on average, across 39 economies worldwide, 40% of adults who bought goods and services online did not reach the minimum target digital financial literacy score, which can be considered as the minimum score for a digitally financially literate person.

The digitalisation of payments brings many benefits but also new risks for consumers, particularly those with low digital financial literacy, including the risk of digital financial exclusion for the most vulnerable.

Using digital payments can also contribute to overspending among some consumers, potentially negatively impacting their financial well-being.

Higher levels of digital financial literacy, in the context of an effective financial consumer protection framework, can raise awareness among consumers of the risks associated with digital payments and provide them with the knowledge and skills to protect themselves online.

Policy makers and financial literacy stakeholders should raise awareness about how digital payments can expose consumers to digital security risks such as online frauds and scams, phishing, account hacking attacks, and data theft, and provide consumers with adequate and updated information to recognise these risks.

The increasing adoption of digital payments brings benefits to consumers but also exposes them to new risks

An increasing number of consumers use digital payments to transfer money and to buy goods and services. According to the latest figures from the Global Findex, between 2021 and 2024, the percentage of individuals who made or received a digital payment increased from 55% to 62% in developing economies and it is 96% across OECD countries1 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022[1]; Klapper et al., 2025[2]). While digital payments bring many benefits to consumers (OECD, 2018[3]), they also expose consumers to a number of risks, including security risks and less control over spending, whose negative consequences can be exacerbated by low levels of digital financial literacy.

Digital payments can bring benefits to consumers

The use of digital payments can bring significant benefits to consumers, notably by enabling more convenient, faster, secure and timely transactions (OECD, 2018[3]). Moreover, the use of digital payments is associated with greater financial inclusion and a decline in the share of informal sector employment (Aguilar et al., 2024[7]). In addition, their use can help keep track of spending patterns and expenses, potentially contributing to better personal financial management.

Digital payments expose consumers to security risks

While digital payments are typically more secure than the use of cash, they carry unique security challenges for consumers. The security risks that consumers can be exposed to when using digital payments notably include account hacking and personal data theft, fraud, and unauthorised transactions. These risks are compounded by low levels of digital financial literacy, and particularly by behaviours that put personal data at risk during financial transactions, such as disregard for basic security procedures.

The results of the OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy, a global study coordinated by the OECD International Network on Financial Education covering 39 economies, show that only a minority of consumers reported regularly changing their passwords on websites they use for online shopping or personal finance (23%), and just under half knew it is unsafe to shop online using public Wi‑Fi networks.

This is concerning given the increasing sophistication of scams and frauds, including through the use of generative artificial intelligence (AI). AI offers new tools to fraudsters, particularly deepfake videos, voices, and documents. Some consumers might not be able to spot these attacks, as demonstrated by the fact that deepfake incidents increased by 700% in the FinTech sector in 2023 (Wall Street Journal, 2024[8]).

The use of digital payments may be associated with less control over spending

The use of digital payments can affect consumer behaviour and may affect some consumers’ control of their spending by lowering the “pain of payment” (Broekhoff and van der Cruijsen, 2024[9]; Meyll and Walter, 2019[10]). This is the negative psychological effect consumers experience when they become cognisant that they have given up a certain amount of their financial resources (immediate pain) or when they become aware that they will or may give up a certain amount of their financial resources in the future (anticipated pain) (Reshadi and Fitzgerald, 2023[11]). This effect depends on several factors, which include the payment method.

Results of the OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy show that this is the case for some consumers. On average, across participating countries and economies, over 20% of adults reported being more likely to buy impulsively when buying online than in a physical shop (see Figure 1). Research indicates that limited digital financial literacy can play a moderating role and mitigate the effect of the use of mobile payments on overspending (Ahn and Nam, 2022[12]).

Risk of digital exclusion

Despite overall positive effects on financial inclusion, the increasing reliance on digital payments can also lead some consumers to experience digital financial exclusion. This may be the case especially among individuals with low digital literacy, those with difficulties accessing the internet, seniors, or people with disabilities. Even when provided with access to the internet, some people might struggle operating devices such as ATMs, POS terminals, computers and smartphones, understanding instructions provided digitally, remembering security codes, or meeting time limits for specific actions (OECD, 2022[13]; 2019[14]).

Difficulties in using digital payment methods can lead to dependency on others and potentially expose individuals to financial abuse (OECD, 2020[15]). Evidence from the Netherlands shows that 2.6 million Dutch adults (18%) did not manage all their banking affairs on their own (Broekhoff, Van Der Cruijsen and De Haan, 2023[16]).

Levels of digital financial literacy are low

Digital financial literacy is a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours necessary for individuals to be aware of and safely use digital financial services and digital technologies with a view to contributing to their financial well-being (OECD, 2022[4]; 2024[5]).

Results from the OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy indicate that digital financial literacy levels may not be sufficient to ensure a safe and informed use of digital payments in light of the opportunities and risks posed by digital financial services (OECD, 2023[6]). The average digital financial literacy score across all participating countries and economies is 53 out of 100 points (55 out of 100 across participating OECD countries). Moreover, across all participating countries and economies, 29% of adults (34% across OECD countries) score the minimum target digital financial literacy score (at least 70 points out of 100). Adults who have higher incomes and higher levels of education score higher compared to adults with lower incomes or lower levels of education.

Results of the same survey also show that, on average, across participating countries and economies, 40% of adults who bought goods and services online did not reach the minimum target digital financial literacy score, which can be considered as the minimum score for a digitally financially literate person (OECD, 2023[6]) (see Figure 2). This is also the case for 27% of adults who reported paying for goods and services in a physical shop with a mobile phone (OECD, 2023[6]).

Figure 1. Impulse buying online

Percentage of adults who agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I am more likely to buy impulsively when I buy online than in person in a shop”

Note: Results for most countries presented in this figure refer to adults with internet access. Results for Croatia, Estonia, Jordan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Poland, and Romania (indicated with an asterisk) refer to all adults, as surveys in those countries did not ask about internet access.

Source: Analysis of the data collected as part of the OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy (OECD, 2023[6]).

Figure 2. Buying goods and services online and digital financial literacy

Note: The target minimum score of digital financial literacy is defined as scoring at least 70 out of a possible 100 points. Results for most countries presented in this figure refer to adults with internet access. Results for Croatia, Estonia, Jordan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Poland, and Romania (indicated with an asterisk) refer to all adults, as surveys in those countries did not ask about internet access.

Source: Analysis of the data collected as part of the OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy (OECD, 2023[6]).

Box 1. Selected examples of financial literacy initiatives on digital payments

Brazil: the central bank created videos with information about the financial system, including scams and frauds on the payment platform Pix.

Hong Kong (China): the Investor and Financial Education Council designed resources, including videos, for primary and secondary schools on the use of payment cards.

Hungary: the central bank, together with a wide range of stakeholders, including the Police, the National Cyber-Security Institute, the Hungarian Banking Association and the Ministry of Justice, launched Kiberpajzs (CyberShield), an information platform for financial consumers, focusing on cyber-security.

Ireland: the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission developed resources on online shopping and safe online payments addressed to adults (Money Skills for Life, Money Hub) and Junior Cycle students (Money Matters).

Morocco: the Moroccan Financial Education Foundation developed several awareness campaigns via social media and radio, focused on using digital payments safely, seeking help in case of problems, budgeting, and responsible financial behaviours.

Portugal: the central bank developed several videos on how to shop safely online, digital financial fraud and what consumers can do to protect their personal data online.

Consumers should be equipped with adequate levels of digital financial literacy to use digital payments in safe and informed ways

As payment transactions increasingly occur online, consumers need to be aware of the security risks they face and have the skills to protect themselves and their personal data in an online environment. Equipping consumers with adequate levels of digital financial literacy is necessary to help counter the increasingly sophisticated scam and fraud attempts. Higher levels of digital financial literacy can also help consumers counter the possible effects of the use of digital payments on spending habits, as well as digital financial exclusion. Box 1 presents selected examples of financial literacy initiatives on digital payments.

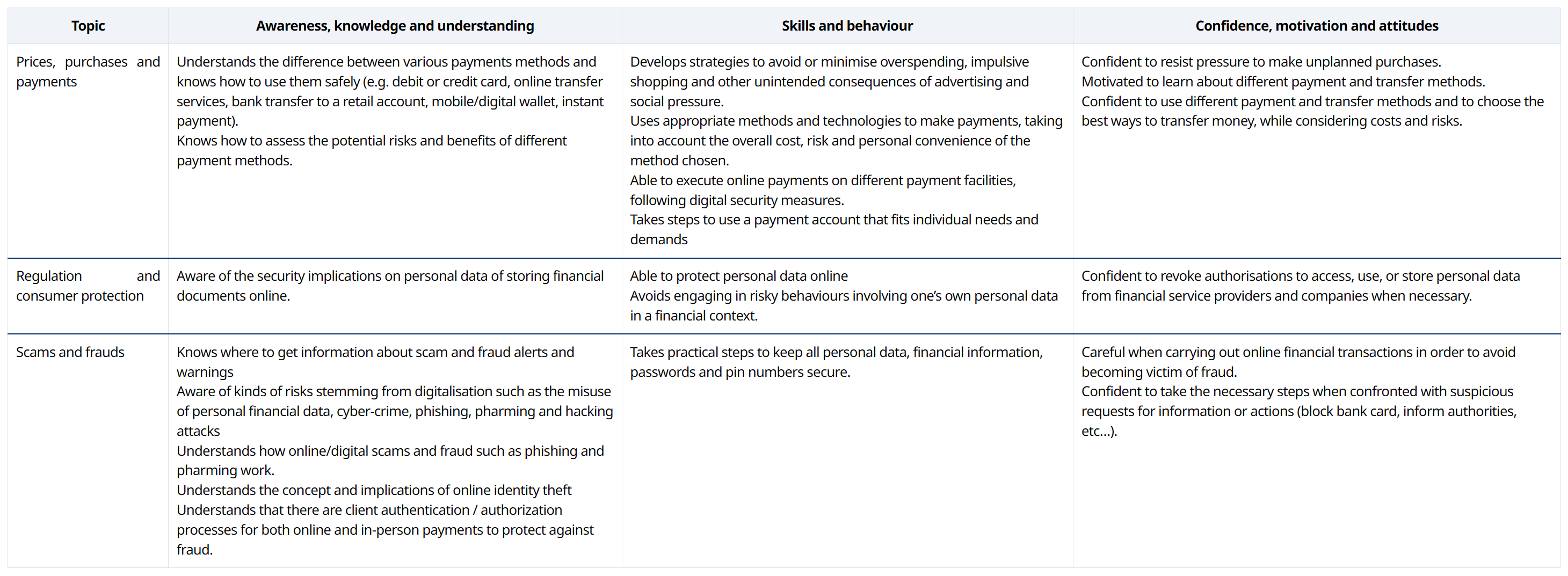

Table 1 provides an overview of some key financial competencies that consumers should ideally have in relation to digital payments based on the Financial competence framework for adults in the European Union (European Union/OECD, 2022[17]). The framework promotes a shared understanding of the financial competencies adults need to make sound decisions when it comes to digital payments, and should inform the design of public policies, financial literacy programmes and educational materials.

Table 1. Financial literacy competencies supporting a safe and informed use of digital payments

Source: (European Union/OECD, 2022[17]), Financial competence framework for adults in the European Union, https://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-competence-framework-for-adults-in-the-European-Union.htm

What can policy makers and other stakeholders working on financial literacy do?

Higher levels of digital financial literacy can help consumers understand the benefits and risks associated with using digital payments and mitigate the potential effects of digital payments on their spending habits. Digital financial literacy initiatives should be part of broader financial literacy policies and should complement financial consumer protection frameworks. Such frameworks should ensure, among other things, that information, control and protection mechanisms shield consumers’ financial assets against fraud and scams online, and encourage the design of quality digital payment products that support individual financial well-being

Higher levels of digital financial literacy can help consumers understand the benefits and risks associated with using digital payments and mitigate the potential effects of digital payments on their spending habits. Digital financial literacy initiatives should be part of broader financial literacy policies and should complement financial consumer protection frameworks. Such frameworks should ensure, among other things, that information, control and protection mechanisms shield consumers’ financial assets against fraud and scams online, and encourage the design of quality digital payment products that support individual financial well-being (OECD, 2024[5]; 2022[18]).

Policy makers and other stakeholders working on financial literacy and education should promote initiatives that enhance financial literacy on digital payments. In doing so, it is important that they co-operate with relevant stakeholders, including financial services providers, FinTechs and civil society organisations working with groups at risk of digital financial exclusion.

In particular, policy makers and other stakeholders working on financial literacy should consider the following actions:

Raise awareness of the benefits linked to the use of digital payments, but also how digital payments can expose consumers to digital security risks such as online frauds and scams, phishing, account hacking attacks, and data theft.

Provide consumers with adequate and updated information to recognise digital security risks, with particular attention to the risks related to AI and psychological manipulation.

Raise awareness about how the use of digital payments might affect individual spending decisions and lead to overspending.

Prompt consumers to appropriately manage their personal data in a digital environment to the extent possible and understand the consequences of sharing or disclosing personal information online.

Encourage consumers to report frauds and scams, including those related to digital transactions, and ensure that they know how to do so through the appropriate channels in their jurisdiction.

Consider the needs of consumers who are at risk of digital financial exclusion, such as those with low digital literacy or without access to the internet, seniors, or people with disabilities.

References

[7] Aguilar, A. et al. (2024), “Digital payments, informality and economic growth”,

[7] Aguilar, A. et al. (2024), “Digital payments, informality and economic growth”, https://www.bis.org/publ/work1196.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

[12] Ahn, S. and Y. Nam (2022), “Does mobile payment use lead to overspending? The moderating role of financial knowledge”, Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107319.

[9] Broekhoff, M. and C. van der Cruijsen (2024), “Paying in a blink of an eye: it hurts less, but you spend more”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Vol. 221, pp. 110-133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2024.03.017.

[16] Broekhoff, M., C. Van Der Cruijsen and J. De Haan (2023), Towards financial inclusion: trust in banks’ payment services among groups at risk, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4627173.

[1] Demirgüç-Kunt, A. et al. (2022), The Global Findex Database 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex/Report (accessed on 23 February 2023).

[17] European Union/OECD (2022), “Financial competence framework for adults in the European Union”, https://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-competence-framework-for-adults-in-the-European-Union.htm (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[2] Klapper, L. et al. (2025), The Global Findex 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex (accessed on 21 July 2025).

[10] Meyll, T. and A. Walter (2019), “Tapping and waving to debt: Mobile payments and credit card behavior”, Finance Research Letters, Vol. 28, pp. 381-387, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2018.06.009.

[5] OECD (2024), G20 policy note on financial well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7332c99d-en.

[6] OECD (2023), “OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy”, OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers, No. 39, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/56003a32-en.

[13] OECD (2022), Financial planning and financial education for old age in times of change | OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers | OECD iLibrary, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/financial-planning-and-financial-education-for-old-age-in-times-of-change_e1d4878e-en (accessed on 28 September 2023).

[18] OECD (2022), G20/OECD High-Level Principles on Financial Consumer Protection, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0394 (accessed on 24 April 2023).

[4] OECD (2022), OECD/INFE Guidance on Digital Delivery of Financial Education, https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/INFE-guidance-on-digital-delivery-of-financial-education.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[15] OECD (2020), Financial Consumer Protection and Ageing Populations, https://www.oecd.org/finance/Financial-consumer-protection-and-ageing-populations.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

[14] OECD (2019), “G20 Fukuoka Policy Priorities on Aging and Financial Inclusion”, https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/g20-oecd-report-on-aging-and-financial-inclusion.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2022).

[3] OECD (2018), G20/OECD INFE Policy Guidance on Digitalisation and Financial Literacy, https://www.oecd.org/finance/G20-OECD-INFE-Policy-Guidance-Digitalisation-Financial-Literacy-2018.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[11] Reshadi, F. and M. Fitzgerald (2023), The pain of payment: A review and research agenda, John Wiley and Sons Inc, https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21825.

[8] Wall Street Journal (2024), Deepfakes Are Coming for the Financial Sector, https://www.wsj.com/articles/deepfakes-are-coming-for-the-financial-sector-0c72d1e5.

Explore further

OECD (2020), Recommendation of the Council on Financial Literacy,

OECD (2020), Recommendation of the Council on Financial Literacy, OECD/LEGAL/0461, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0461

OECD (2012), G20/OECD High-Level Principles on Financial Consumer Protection 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/48cc3df0-en

OECD (2023), "OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy", OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers, No. 39, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/56003a32-en

OECD (2024), OECD/INFE survey instrument to measure digital financial literacy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/548de821-en