Research Summary

We investigate why firms imitating the same competitor’s strategy in the same environment often replicate different components of that strategy. We argue that such divergence can arise because firms vary in the internal interdependencies that underlie their strategies. When a firm significantly differs from a competitor in how one component of its strategy interacts with other components, the consequences of replicating the competitor’s choices about that component are harder to anticipate, making imitation less likely. We discuss how imitators’ internal coordination mechanisms may help mitigate barriers to imitation arising from interdependence asymmetries and test our resulting hypotheses in the context of esports, where small teams of professional video-game players compete in high-stakes tournaments.

Managerial Summary

We investigate why firms observing the same competitor often imitate different aspects of that competitor’s strategy. We argue that this variation stems from each firm’s unique internal connections between activities. When a competitor’s practice is closely linked to other parts of their strategy, imitation becomes riskier if similar links do not exist in the focal firm—making imitation less likely. Using data from esports teams, where both strategic choices and coordination are observable, we show that these differences can act as barriers to imitation. However, strong communication or shared experience among decision-makers helps overcome such barriers. Our results may caution managers against indiscriminately copying “best practices”: the highly competitive teams we studied considered not only what competitors did, but also whether those practices fit their own processes and structures.

1.INTRODUCTION

When and why do organizations imitate their competitors' strategies? These questions have a long history in economics and sociology (Alchian, 1950; Coleman et al., 1957) and are an active focus of research on strategy and organization theory (Naumovska et al., 2021). Strategy scholars have been interested in predicting imitation, largely to answer the field's fundamental questions of why firms differ and what sustains these differences. Studying the drivers of imita tion should help answer these questions because, intuitively, imitation reduces heterogeneity among organizations. The more firms imitate their competitors, the more we should expect firms to resemble one another over time. A large body of work has reinforced this expectation by showing how imitation can lead to the homogenous adoption of practices in various indus tries (e.g., Beaman et al., 2021; Griliches, 1957).

The idea that imitation leads to convergence may be intuitive, but research also suggests that it is not inevitable. Firms' strategies comprise multiple practices and choices relating to their activities (e.g., Csaszar & Siggelkow, 2010; Van den Steen, 2017). Multiple firms might imi tate the same competitor but adopt different components of the competitor's strategy, with each firm ultimately displaying distinct strategies. Consider the widely discussed strategy pioneered by Southwest Airlines in low-cost aviation, which included using a homogeneous fleet, point to-point services, secondary airports, direct marketing, payment for frills, and flexible union rules (Kim & Mauborgne, 2002; Porter, 1996). Several competitors replicated distinct sets of Southwest's practices, such that several distinct strategic models can now be traced back to Southwest1 (Majerova & Jirasek, 2023). Another example is Snapchat, a social media platform that pioneered casual, short-form, vertical, and ephemeral video content. Instagram and TikTok imitated Snapchat's strategy (Chandonnet, 2024), but each of them replicated substantially dif ferent elements of Snapchat's approach. Instagram incorporated disappearing direct messages as well as ephemeral, curated content delivered via a social graph–driven feed (Choi & Sung, 2018). In contrast, TikTok incorporated casual, vertical-format, persistent public videos supported by algorithm-driven discovery (Zulli & Zulli, 2022).

Prior research has attributed such differences in firms' imitative choices to environmental factors, such as IP laws precluding imitation of some practices of a competitor and not others (Klevorick et al., 1995), competitors taking measures to protect or hide some of their practices (Sharapov & MacAulay, 2022), or the greater complexity and thus lower replicability of some practices relative to others (Ethiraj et al., 2008). However, this work remains limited in discern ing why firms exposed to the same competitor in the same environment would imitate different strategy components. The theoretical models of diffusion that underlie much of the work on the antecedents of imitation implicitly characterize the firms involved as unitary actors making binary choices (Banerjee, 1992; Coleman et al., 1957). As a result, this prior work has primarily focused on drivers external to the firm, such as technological uncertainty and competitive inten sity (Lieberman & Asaba, 2006). However, organizations' internal structures and decision making processes also profoundly influence their strategic choices (Leiblein et al., 2018; Siggelkow, 2002). Whether and how these factors shape differences in the components firms choose to imitate remains an open question.

To fill this gap, we build a theory of imitation that integrates prior thinking about the sub ject with research in the behavioral tradition that conceives of firms as adaptive coalitions (Cyert & March, 1963). This work conceptualizes strategy as a set of interdependent choices made by specialized decision-makers about the different components of a firm's activity (Raveendran et al., 2020). The structure of components' interdependencies might vary both within and across firms (Milgrom & Roberts, 1995). For instance, in the aviation industry, fleet planning activities might be most closely intertwined with engineering and maintenance at some airlines but with demand-side functions (e.g., sales and marketing) at other airlines (Merkert & Hensher, 2011; Sherali et al., 2006). We argue that such differences help explain imitation because they influence decision-makers' uncertainty about the consequences of adopting another firm's practices. When a firm and its competitor differ in how a given compo nent of its strategy interacts with others, the consequences of replicating this component become less predictable for the imitator. The pattern of interdependence that made the choice successful in one organization might not be present in the other, making it harder to gauge whether the choice will be as effective and what spillovers it will generate for other activities (De Figueiredo et al., 2019; Rawley, 2010). As a result, we expect that a firm is more likely to imitate a competitor's choice about an activity if that activity interacts with other activities simi larly in the two firms. Returning to our aviation example, an airline is more likely to imitate another firm's fleet management practice if fleet management is linked to other activities simi larly across the two firms.

The mechanism underlying our theory leads to additional predictions about organizational factors that might promote or prevent imitation. If differences in interdependence patterns cre ate a barrier to imitation by elevating the uncertainty experienced by decision-makers about the consequences of adopting a practice, then this barrier should be lowered when decision-makers possess stronger coordination mechanisms to help them alleviate this uncertainty. Coordination mechanisms might include explicit communication among decision-makers responsible for dif ferent activities or shared mental representations developed through collaborative experience (Hansen, 1999; Srikanth & Puranam, 2011; Thompson, 1967). These mechanisms should help decision-makers reduce uncertainty by sharing information that helps better predict the impact of imitation or increase their confidence in their collective adaptation to the consequences of imitation despite this uncertainty. Hence, we expect that differences in interdependence pat terns will act as less of a barrier to imitation for organizations whose decision-makers can more easily coordinate with one another.

We test these ideas empirically in the context of esports, an industry in which small teams of professional video game players compete for substantial prizes. Our data are drawn from major tournaments of the popular esport game Defense of the Ancients 2 (DOTA 2) (Ching et al., 2021, 2024; Clement, 2023). The setting provides detailed digital traces of teams' behaviors and internal structures, providing greater visibility into the mechanisms of interest than prior research has typically had. This visibility allows us to infer activity-level choice differences between competing teams. Within teams, we can capture the level of interdependence between every pair of players based on the degree to which they have historically been involved in sequences of shared activity with each other. Also, because tournament matchups between teams are effectively randomized, exposure to competitors' practices is largely exogenous, enabling us to distinguish the drivers of imitation from the drivers of exposure (de Vaan & Stuart, 2019). Supporting our theory, we find that teams are substantially more likely to imitate competitors' choices regarding a specific activity if the focal team and its competitors have a more similar pattern of interdependence between that activity and others. As these patterns of interdependence diverge, imitation becomes less likely unless the decision-maker responsible for that activity has significant collaborative experience with their teammates or communicates extensively with them, better enabling them to resolve this uncertainty.

Our study makes several contributions to the literature on interfirm imitation. By examining the decision processes within organizations underlying the choice to imitate another firm's practices, we provide a novel explanation for differences in firms' imitative behaviors (Makadok et al., 2018). Our findings help explain how imitating firms can diverge in their strategies even when the target of their imitation efforts is the same. We bridge the literatures on (intra-)orga nization design and (inter-)organizational imitation to demonstrate how differences in firms' interdependence structures can lead to systematic differences in their choices of what to imitate externally (Posen et al., 2023; Puranam, 2018). Doing so also highlights that symmetry in interdependence structures can promote the flow of practices between firms, adding to our understanding of how practices might diffuse across a population of firms (Comin & Hobijn, 2010; Griliches, 1957). Finally, we contribute methodologically by demonstrating an empirical approach for estimating the relationship between internal activity structure and strat egy in a large population of organizations, advancing research on this topic that has largely drawn on computational models.

2.THEORY

Scholars across a wide range of disciplines have studied the spread of practices between compet ing organizations. The earliest work on this topic in the social sciences drew on biology in char acterizing imitation as a natural outcome of pursuing evolutionary fit, leading to the transmission of successful “mutations” through a population (Alchian, 1950; Penrose, 1952). Building on these foundations, research has examined “peer effects” or social learning, referring to firms' propensity to replicate the choices of those around them (Banerjee, 1992; Conley & Udry, 2010). Social theorists have also highlighted the role of legitimacy and network connections in shaping the diffusion of practices (Coleman et al., 1957; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Management scholars have refined and applied these insights to explain the spread of practices and strategies across populations of firms, with consequences for firm diver sification (e.g., Haveman, 1993), capital structure (e.g., Leary & Roberts, 2014), governance (e.g., Davis, 1997), as well as operational efficiency and incentives (e.g., Mahajan et al., 1988).

In much of this literature, imitation has been cast as the opposite of innovation (Mansfield, 1961). As a result, theories have traditionally predicted that imitation leads to con vergence in a population of firms, with firms becoming more alike by converging towards prac tices that are the most efficient (Griliches, 1957) or socially desirable (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). However, some work has questioned whether imitation inevitably leads to homogeneity among competitors. Alchian (1950, 219), for instance, noted that firms might “unconsciously innovate” through erroneous imitation. Studies of misspecified learning models have also noted the poten tial for inadvertent variation in what imitators adopt due to confirmation bias (e.g., Rabin & Schrag, 1999), misattributions (e.g., Bushong & Gagnon-Bartsch, 2023), or selective attention (e.g., Schwartzstein, 2014).

Research on strategy has further highlighted that such variation need not arise inadvertently and might be consciously chosen by the imitator (Posen et al., 2023). This research has noted that imitation might be multidimensional: organizations' activities and strategies are composed of various distinct elements, allowing competitors to be selective in replicating some elements of one another's strategy and not others (Csaszar & Siggelkow, 2010; Rivkin, 2001). As a result, an organization might blend some components of its competitors' strategies with its own capa bilities, leading to novel combinations. This suggests that imitation might facilitate recombina tion rather than eliminate variation, potentially increasing heterogeneity among competitors.

Given the meaningful implications of selective imitation, scholars have investigated when and why it happens. Some research suggests that it can arise because some elements of a target technology might be less visible or available than others. For instance, the early power looms the Boston Manufacturing Company used to establish the US textile industry were partial imita tions of those in England. Because the export of this technology was restricted, only some of its components could be observed and imitated, and the remainder had to be improvised (Morris, 2012; Rosenberg, 2010). Such variation can also arise from differences in institutional environments or competitive pressures. For instance, early studies noted that cross-region het erogeneity in the adoption of technological advances in farming arose from regional differences in regulations and market conditions (Griliches, 1957). The imitation of some strategy elements might also be precluded by laws, such as intellectual property protections, leaving only the remainder open to imitation (Klevorick et al., 1995; Pisano, 2006). Alternatively, some compo nents of a firm's strategy might be costly to imitate because of the firm's efforts to hide them (Alcacer & Zhao, 2012) or because of the tacitness of the knowledge underlying these compo nents (Autio et al., 2000).

However, despite their importance, the aforementioned factors paint an incomplete picture of the drivers of variation in firms' imitative choices. Even firms imitating a competitor's strat egy in the same environment often imitate different components of that strategy. Consider the example of Southwest Airlines discussed earlier. Most known drivers of partial imitation are unlikely to apply to this example. Southwest's practices were highly visible and not protected by IP restrictions. Alternatively, consider Apple's pioneering smartphone strategy that established the iPhone ecosystem. As with Southwest, this strategy included several components rep resenting key choices about the product's physical appearance, software, functionality, and supporting ecosystem (Adner, 2022). Although Apple's strategy has inspired many imitators (e.g., Samsung, Xiaomi, HTC, Lenovo, and Huawei; see Barboza, 2013), these imitators substan tially differ in which strategy components they replicated and how they did so (Wang et al., 2023). Again, prior research offers little guidance in explaining these differences, given that the target of imitation is the same and many of these imitators operate in similar environments.

Research on interfirm imitation, rooted in models of diffusion, has gleaned substantial insight into which firms engage in imitation and when they do so (Lieberman & Asaba, 2006). However, given the purpose of these models is to explain the spread of a practice across a popu lation, they typically characterize the firms involved as unitary actors, abstracting away from organizations' internal processes underlying the choice to imitate a competitor's practices. Thus, this research has principally focused on antecedents to imitation that are external to the imitat ing firm, such as those relating to environmental or market conditions (Naumovska et al., 2021). By contrast, a different body of literature has highlighted the role of organizations' internal designs in shaping their strategies (e.g., Arrow, 1985; Cyert & March, 1963). This research has documented that the nature of the interdependencies within organizations can profoundly shape the imperatives of its decision-makers and thereby drive variance in their choices (Argyres & Silverman, 2004; Puranam, 2018). In what follows, we bridge these litera tures to systematically consider the processes within organizations that drive variance in these decisions, helping explain the emergence and persistence of heterogeneity between competitors.

2.1Mismatchininterdependencies and component-level imitation

In addressing our research question, we treat firms as organizational systems in which several

interdependent decisions are made in a coordinated manner (Kretschmer et al., 2012;

Milgrom & Roberts, 1990). The components that make up an organization's strategy refer to the

decisions made about its different activities. Two components are interdependent when

the value of choices made about one varies depending on choices made about the other

(Natividad & Rawley, 2016; Rivkin & Siggelkow, 2003). An extensive body of research has

shown that complementarities between components can enhance firm performance

(e.g., Milgrom & Roberts, 1990; Novak & Stern, 2009). Complex interdependencies between the

components of a firm's strategy also create causal ambiguity that can shield it, in aggregate,

from being imitated by competitors (Rivkin, 2001; Ryall, 2009). However, managing interdepen

dencies between activities requires greater coordination within the firm, which is costly

(Rawley, 2010; Zhou, 2011). These interdependencies can arise from, for example, consumer

preferences for coherent sets of component choices; historical organizational endowments, such

as routines that generate value across specific combinations of components; or distinctive

resources that are used simultaneously to deploy several components (Feigenbaum &

Gross, 2024).

The extent and nature of interdependencies between components can vary substantially within and across organizations (Gokpinar et al., 2010; Sosa et al., 2015). Within an organiza tion, some sets of components might be highly interdependent, whereas others might be much less so. Similarly, a certain pair of components might be highly interdependent in one organiza tion but function relatively independently in another (Simon, 1962). For instance, the product design activities in one smartphone company might be most closely intertwined with its technology-focused activities (e.g., R&D), whereas those in another might be more closely intertwined with customer-facing activities (e.g., marketing). As we will argue, these differences can systematically influence firms' propensity to imitate each other's product design practices.2

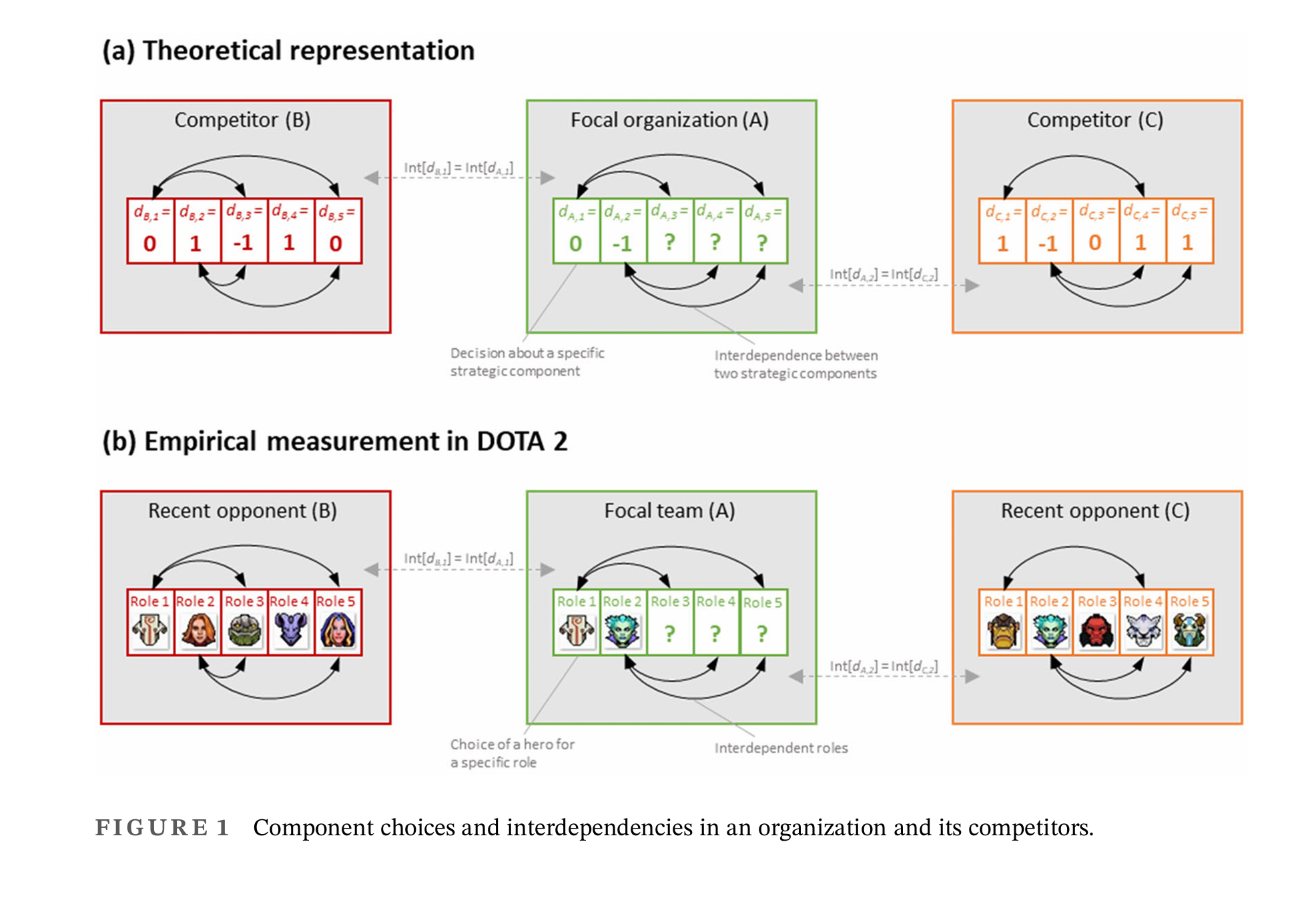

Figure 1a illustrates our conceptualization, which closely resembles the one featured in evo lutionary models of search in which actors make choices about components with varying pat terns of interdependence (e.g., Levinthal, 1997). In the figure, organization A and its competitors B and C each make choices relevant to five strategy components. The different values (−1, 0, or 1) represent alternative choices that can be made about each component. For instance, such choices for an airline might include the type of aircraft to use (e.g., wide body, narrow body, mixed), the range of geographic coverage (regional, national, or international), the airport type serviced (hubs, secondary airports, or mixed), and the business model (full ser vice, low cost, or charter) (Ryall, 2009). The figure shows the interdependencies of components 1 and 2 with the other components in each of the three organizations. These patterns can be similar or different between competitors. For example, the pattern of interdependencies ½ surrounding component 1 in organization A is similar to the corresponding pattern Int dA,1 Int dB,1 ½ incompetitor B but not to the pattern Int dC,1 the pattern of interdependencies Int dA,2 ½ incompetitor C. The reverse is true for ½ surrounding component 2 in organization A.

The key mechanism by which organizations' interdependence structures influence their strategic choices is by shaping their decision-makers' ability to predict the impact of these choices (e.g., Aggarwal & Wu, 2015; Clement, 2023). The impact of these choices depends not only on their effectiveness in isolation—for instance, how effectively a practice would accom plish its intended function under ideal conditions—but also on how well the choices fit an orga nization's environment. This fit is partly influenced by the spillover effects of a choice about one component on other components that depend on that choice (Henderson & Clark, 1990; Levinthal, 1997). For instance, a logging company's choice of practices for removing knotty wood from a fallen tree depends on the perceived effectiveness of those practices as well as the implications of those practices for the operations of the lumber mill that will subsequently pro cess the wood (Casadesus-Masanell et al., 2008).

Foreseeing such spillovers can be difficult: a broad literature underscores the difficulty of predicting the impact of an organization's choices given the interdependencies between deci sions (Clement, 2023; Martignoni et al., 2016). Decision-makers within firms are, on average, more likely to make a particular choice when its consequences involve less uncertainty (Camerer & Weber, 1992; Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988). Such consequences include those of the focal activity itself and the spillovers that the choice might generate for the organization's other activities (Rawley, 2010).

As a result, the patterns of interdependencies within which a component is embedded might be an important factor affecting the imitation of choices relating to it. Specifically, an organiza tion is more likely to imitate a competitor's choice about a component if the component inter acts with others similarly at the two organizations. This similarity helps decision-makers predict the impact of a choice not by relying fully on rational deduction (i.e., computing “from scratch” the choice's likely impact on other components) but by relying on analogical reason ing: the likelihood of the practice performing similarly in both organizations increases if both organizations have a more similar pattern of interdependence in which the relevant activities are embedded (Gavetti et al., 2005; Szulanski, 1996). By contrast, asymmetry in interdepen dencies decreases the predictability of the disruptions this choice generates for the organiza tion's other activities, making consensus around the choice harder to reach within the organization3 (De Figueiredo et al., 2019; Feigenbaum & Gross, 2024).

Hypothesis 1. An organization is more likely to imitate a competitor's choice about a strategic component if the pattern of interdependence between this component and others is similar in the two organizations.

Our arguments so far suggest that the imitation of choices relevant to a strategic component might be limited by the level of similarity between competitors in the interdependence structures within which that component is embedded. As shown in Figure 1a, the focal organi zation is more likely to imitate a choice about component 1 from competitor B than competitor C because component 1 interacts with other components more similarly in the focal firm and competitor B. However, the reverse is true for component 2, for which the focal firm's interdependence patterns are more similar to those of competitor C. A mismatch in interdependence structures generates uncertainty in predicting the impact of imitation in the focal organization, making imitation less likely.

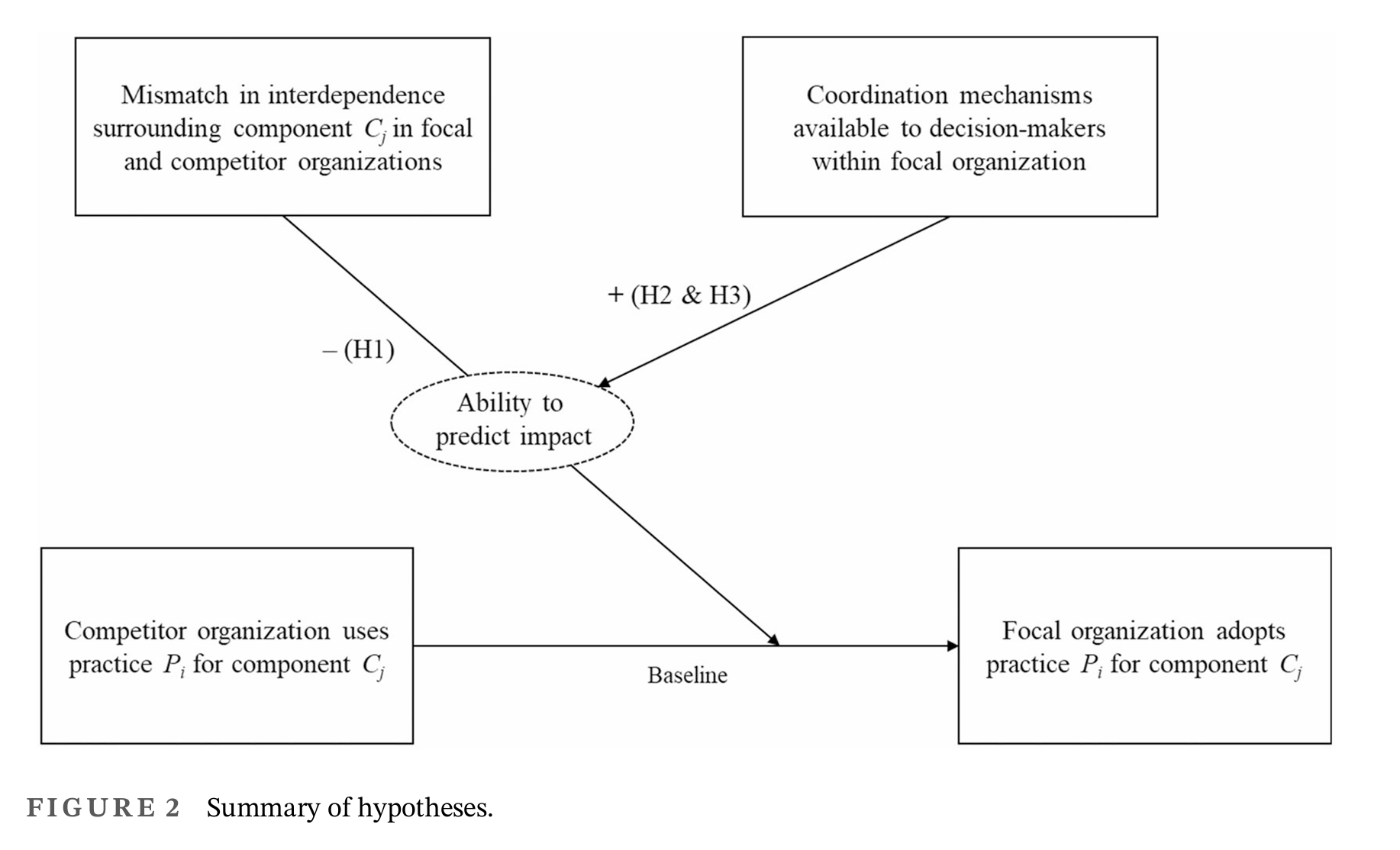

Figure 2 provides a summary of this prediction and its underlying mechanism, that is, the heightened uncertainty regarding the implications of imitation arising from a greater mismatch in the interdependencies between the organization and its competitor. If uncertainty is the fac tor limiting imitation in the face of such a mismatch, organizational coordination mechanisms that enable decision-makers to collectively resolve such uncertainty should be especially potent in promoting imitation when the mismatch in interdependencies is greater.

Coordination mechanisms are likely to be relevant because strategic decisions in most orga nizations are influenced by several decision-makers who hold specialized knowledge about dif ferent strategic components (Cyert & March, 1963). Interdependent specialists often struggle to understand the collective consequences of new choices (Clement, 2023; Puranam & Swamy, 2016). Interdependence mismatch with a competitor makes predicting the conse quences of adoption more difficult, both for the focal component and for others that have inter dependencies with it (De Figueiredo et al., 2019; Rawley, 2010). As a result, an organization is unlikely to imitate a component choice of a mismatched competitor unless its decision-makers can reinforce their confidence about successfully implementing the same choice. Coordination mechanisms may enable decision-makers to do so either by alleviating the uncertainty about its impact or by enhancing confidence in their ability to collectively adjust to the consequences of adoption despite this uncertainty (Galbraith, 1973). Below, we consider the role of two funda mental channels by which decision-makers within organizations can coordinate, explicitly via direct communication with each other or implicitly via shared experience developed over time (Huckman et al., 2009; Srikanth & Puranam, 2011).

A considerable body of evidence supports the notion that “communication with one's con tacts helps to resolve the uncertainty surrounding the value of an innovation” (Davis, 1991, 593). Within an organization, effective communication allows decision-makers to resolve uncer tainty about how a choice regarding one part of the organization could impact other parts and, consequently, the outcomes for the organization in aggregate (Garicano & Wu, 2012; Van de Ven et al., 1976). It also allows different decision-makers to engage in mutual adjustments as they seek to adapt their behavior to fit newly adopted practices (Thompson, 1967). Established communication patterns should reinforce decision-makers' confidence that the different parts of the organization can adapt as necessary to localized changes.

Overall, these arguments suggest that communication among decision-makers should allow them to collectively reduce uncertainty about the impact of adopting new practices locally and increase their confidence about adapting through mutual adjustment even if some uncertainty remains:

Hypothesis 2. When an organization and its competitor show different patterns of interdependence between a strategic component and others, the organization is more likely to imitate the competitor's choice about this component if the organiza tion's decision-makers communicate more frequently.

As an alternative to explicit communication, decision-makers can also resolve uncertainty by relying on a tacit understanding of the interdependencies between the components they spe cialize in. We focus on prior collaborative experience among decision-makers as a way of gener ating tacit understanding.

Familiarity among decision-makers resulting from repeated collaboration facilitates a better understanding of how different decision areas relate to one another and of how decisions in one area impact others (Edmondson et al., 2003; Nelson & Winter, 1982). Relatedly, organiza tional research has extensively documented the “disambiguating quality of strong ties” (Strang & Still, 2006). For instance, Hansen (1999) found that, that strong inter-unit ties within an organization are especially beneficial for decision-making in projects involving more com plex and less codifiable forms of knowledge. These relationships facilitate the development of a shared understanding—a “relationship-specific heuristic” that enables more effective engage ment between individuals from the different units (Hansen, 1999, 88). Mizruchi and Stearns (2001) demonstrated a similar relationship in the context of a bank, where managers with strong ties to their peers are better equipped to close deals involving high uncertainty with their corporate clients. These peer relationships enable bankers to vet deals in advance more effec tively and identify actions that would meet the approval of their organization.

Hence, we expect collaborative experience among decision-makers to affect the imitation of strategy components in the same way as explicit communication. A shared understanding developed through repeated collaboration will help decision-makers reduce uncertainty about the impact of adopting new practices locally and feel confident in their ability to adapt through mutual adjustment, even if some uncertainty remains. Hence, we predict the following:

Hypothesis 3. When an organization and its competitor show different patterns of interdependence between a strategic component and others, the organization is more likely to imitate the competitor's choice about this component if the organiza tion's decision-makers have more collaborative experience.

Click to read more