Abstract

This research examines how the movements an interface requires of a consumer—that is, its “kinesthetic properties”—can alter what a consumer attends to when responding and in turn change the response itself. We compare the kinesthetic properties of two ubiquitous scale formats: slider and radio-button scales. Six studies (plus four in the web appendix) show dragging a slider (vs. clicking a radio button) elicits responses that are closer to the scale starting point. This effect occurs because the slider allows participants to engage with the scale as they consider their options. When dragging past each response option, attention is directed to that option, increasing its chance of being selected. Supporting this account, sliders only result in responses closer to the starting point when participants physically drag the cursor across options to their desired response, not when they directly click on it. Furthermore, participants dragging a slider interact with the scale earlier in the judgment process and exhibit a greater visual focus on left-side (vs. right-side) options on the scale compared to participants clicking a radio button. These findings suggest that marketers, graphic designers, and researchers should consider how the kinesthetic properties of digital interfaces may shape consumer judgment.

People regularly make judgments or indicate preferen ces on digital interfaces. For example, mobile app users can express their preference for partners by swiping,customers can purchase items by scanning their fingerprint, and music streamers can skip songs by tapping their head phones. These response formats differ in their kinesthetic properties—the physical movements used to generate a response. In this research, we explore how these kinesthetic properties can influence judgments and choices expressed on different response-scale formats.

Capturing consumer thoughts and values with response scales is a cornerstone of marketing, public policy, and behavioral research. The kinesthetic properties of these response scales have become particularly diverse in the past decade with the growth of new technologies: people can indicate preferences and make choices by clicking a radio button, sliding a scale, scrolling through a drop-down menu, holding down on a smartphone screen, and more. At first glance, such a small difference in format seems incon sequential—the same prompt with the same choice options should elicit the same response regardless of the physical movements used to indicate that response. By contrast, we suggest that kinesthetic properties are not a benign feature of a response scale because they can shape the psychological process used to generate the response. Consequently, the kinesthetic properties of a response scale could meaningfully influence the resulting data.

This article builds on research demonstrating that the for mat of response scales can shape the answers people give by influencing how they interpret both the question and choice set, as well as the process by which they formulate their response. Specifically, the literature on response scales can be broadly classified into three categories: structural proper ties (Jacoby and Matell 1971; Krosnick 1999; Nowlis, Kahn, and Dhar 2002; Schwarz 1999; Weijters, Cabooter, and Schillewaert 2010; Wildt and Mazis 1978), semantic proper ties (Krosnick 1999; Kyung, Thomas, and Krishna 2017; Schwarz 1999; Schwarz et al. 1985, 1991; Schwarz, Grayson, and Kn€auper 1998; Weijters et al. 2010; Weijters, Geuens, and Baumgartner 2013; Wildt and Mazis 1978), and visual properties (Abell, Morgan, and Romero 2024; Schwarz et al. 1998; Thomas and Kyung 2019; Weijters, Millet, and Cabooter 2021). Decades of methodological research find that the structural properties of a response scale, which we define as the number and order of response options on a scale, influence the responses that people pro vide. For example, options listed first in a set are more likely to be selected (Krosnick 1999). The semantic properties of a response format, which we define as the kinds of labels used for the scale points, also shape how people interpret the question and process the options. For example, labels that go from good (1) to bad (5) are incongruent for people in the United States, who hold a “bigger is better” belief and, as a result, can systematically bias judgments (Kyung et al. 2017). Finally, prior research finds that the visual properties of scales can affect people’s responses, mostly because of magnitude perceptions. For example, respondents use the visual distance between response options as a cue for con ceptual distance, leading to more extreme responses for ver tical scales on which option display is typically more compact (Weijters et al. 2021). Furthermore, Thomas and Kyung (2019) find that in willingness-to-pay (WTP) ques tions, the visual depiction of a number line on a slider or a radio-button scale reduces magnitude judgments, leading to more extreme responses than a text box.

We suggest that in addition to structural, semantic, and visual properties of response formats, the kinesthetic prop erties of the scale also influence people’s responses. Our theoretical framework rests on two propositions. First, the movements a person makes when indicating a judgment or making a decision direct attention to certain options in the choice set, and second, people are more likely to select options that receive more of their attention. We expand on these propositions in the following section.

MOVEMENT, ATTENTION, AND CHOICE

The motor and cognitive systems of the human brain

evolved synchronously and codependently, resulting in a link between physical movement and both automatic and

deliberate attention (Ballard et al. 1997; Tversky 2019;

Wilson 2002). For example, research finds that people

process peripheral visual input more when walking versus

sitting (Cao and H€andel 2019) and engage in “body-ori

enting” behavior when directing their eye gaze to environ

mental stimuli, such as moving their head toward the

object of attention (Khan et al. 2009). This link between

attention and movement is established early in human

development (Bushnell and Boudreau 1993), with infants

exhibiting motor movement and attention coupling as early

as their first month (Robertson, Bacher, and Huntington

2001). Physical movement and attention are so intertwined

that people move their heads when internally directing their

attention to something in visual memory (Thom et al.

2023), and children as young as two years of age learn to

use an adult’s hand movements (Deák et al. 2014) and

body cues (Paulus, Murillo, and Sodian 2016) to determine

what the adult is attending to.

Building on this research, we propose that even trivial movements involved in responding to a question can alter the focus of attention when providing a response. A shift in attention is consequential because judgments are typically constructed at the time of elicitation (Payne, Bettman, and Johnson 1993; Schwarz 2007), rendering the selection peo ple make dependent on what they pay attention to when constructing their response. Indeed, recent research has documented a strong, bidirectional link between attention and choice (Armel, Beaumel, and Rangel 2008; Krajbich and Rangel 2011; Lim, O’Doherty, and Rangel 2011; Milosavljevic et al. 2012; Orquin, Lahm, and Stojic 2021; Orquin and Loose 2013; P€arnamets et al. 2015; Shimojo et al. 2003; Smith and Krajbich 2018, 2019). External fea tures that increase visual salience of an option, such as rela tive surface size (Chandon et al. 2009; Lohse 1997), being centrally displayed (Atalay, Bodur, and Rasolofoarison 2012), and color of packaging (Milosavljevic et al. 2012), increase the attention to that choice option and subse quently its likelihood of being selected. Furthermore, research finds that exogenously directing gaze affects choice (Armel et al. 2008; Lim et al. 2011; P€arnamets et al. 2015). For example, slightly manipulating how much time participants look at one snack item (vs. another) increases the likelihood of their choosing to eat that snack (Armel et al. 2008). Although the tasks and types of attention vary across studies, the evidence converges on the conclusion that both automatic and deliberate attention affect choice. More specifically, the more that people attend to an option, the more likely they are to choose it.

In this research, we expand the work on attention and choice by introducing a grounded-cognition perspective that highlights the role of physical movement in a response scale in determining what people attend to and, ultimately, how people make judgments and choices. We next delin eate our empirical context and predictions.

PRESENT RESEARCH

In this research, we test the effect of response-scale

kinesthetics by comparing responses on radio-button scales

with responses on slider scales, two ubiquitous scale types

often used interchangeably despite differing in their kines

thetic properties. For radio buttons, a respondent must click

the cursor directly on the desired response; for a slider, a

respondent holds the cursor down and drags it past other

possible selection options to land on the desired response.

Importantly, although prior work has compared sliders with other scales, the scale manipulations of prior designs confound kinesthetic properties with other differences (Bosch et al. 2019; Funke 2016; Liu and Conrad 2019). For example, Liu and Conrad (2019) compared a 101-point slider scale defaulted on 0, 25, 50, 75, or 100 with a textbox scale. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they found respondents using the slider scale were more likely to select their default starting position than those using a textbox without a default starting position.

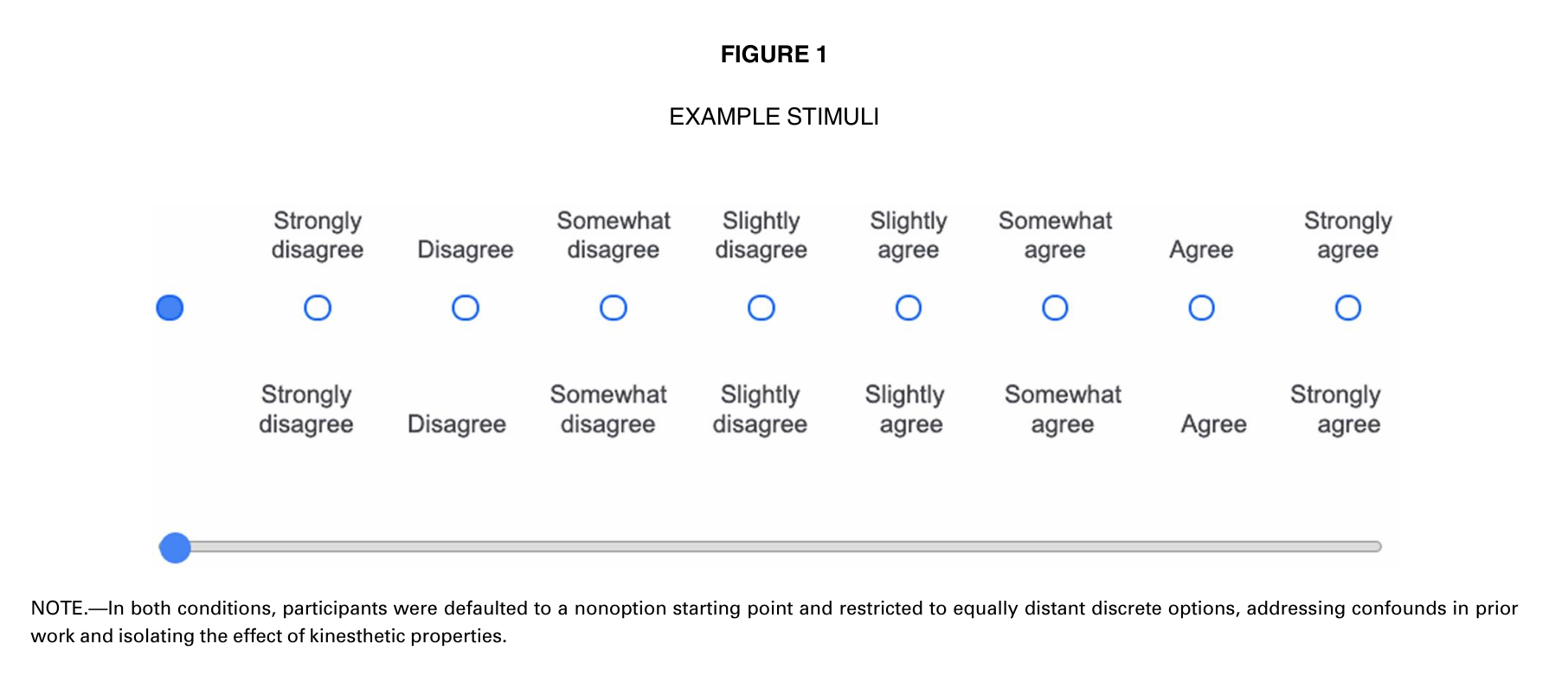

In contrast to that work, we argue that even when con trolling for the presence of a starting point, slider and radio-button scales will yield different responses because the scales differ in the physical movements required to select a response. To isolate the impact of these kinesthetic properties, we address the starting-point confound in prior work by including a preselected “nonoption” starting point for both the slider and radio-button scales that the person is required to unselect to respond. This nonoption starting point ensures neither the slider nor the radio button starts on a preselected response and that any difference between these scales is not simply due to the presence of a starting position, as prior research suggests. In addition to holding the starting point constant, we restrict the slider to the same discrete response options with the same spatial dimensions as the radio buttons to ensure that these two formats pro vide the same option sets. Thus, the only difference between the two conditions is whether the participant must drag a slider or click a radio button (figure 1). This design enables a more rigorous test of the effect of a scale’s kines thetic properties.

We propose that the kinesthetic properties of the slider scale influence the response process respondents use. With a radio-button scale, the process of responding requires two steps. First, respondents must consider the options and then use the scale to indicate their choice. By contrast, with the slider scale, the consideration of response options and the usage of the scale can be integrated: respondents might nat urally consider options as they are using the scale, dragging past each option, considering it in turn, and stopping to indicate their choice. These different sequences evoke dif ferent patterns of attention, which affect subsequent judgment.

Specifically, we argue that the physical action of drag ging a slider guides the order in which respondents attend to the options for consideration, from the leftmost option to the rightmost one, until they arrive at an acceptable response. As respondents sequentially drag their cursor across each option, they pay attention to that option, and this additional attention increases the likelihood that they will select it. Thus, the action of dragging the slider biases responses toward the starting point of the scale because this action directs a greater relative portion of attention to ear lier values on the scale than a radio-button scale.

For example, consider the following question: “Taken all together, on a scale from 1 to 7, how happy are you?” Respondents begin considering options by dragging the slider. As they drag the slider to “1,” their attention is directed to this option, and they momentarily consider it. The additional attention to this option increases the likelihood that it is selected. If this option is not deemed appropriate, they will move to the next value, “2.” Again, they momentarily consider this option, increasing its likeli hood of being selected. This process continues until they choose an appropriate option. By contrast, the radio-button scale does not typically guide attention by inviting people to physically “travel” through each response option, result ing in responses that are less skewed toward the starting point of the scale than with the slider. More formally, we hypothesize the following:

H1: Dragging a slider to (vs. clicking) a response yields responses that are closer to the starting point of the scale.

Importantly, we propose that this hypothesized effect is driven by how people interact with the scale, which in turn affects attention to the options on the scale. With a radio- button scale, people first consider options and click the scale after making a judgment; conversely, with a slider scale, people can engage with the scale before making a judgment, attending to options as they sequentially drag past them. This is put formally as the following:

H2: People engage with the slider scale earlier in the judg ment process than with a radio-button scale.

H3: The difference in relative attention between the left- side and right-side options on the scale is greater for people dragging a slider than for those clicking a radio-button scale.

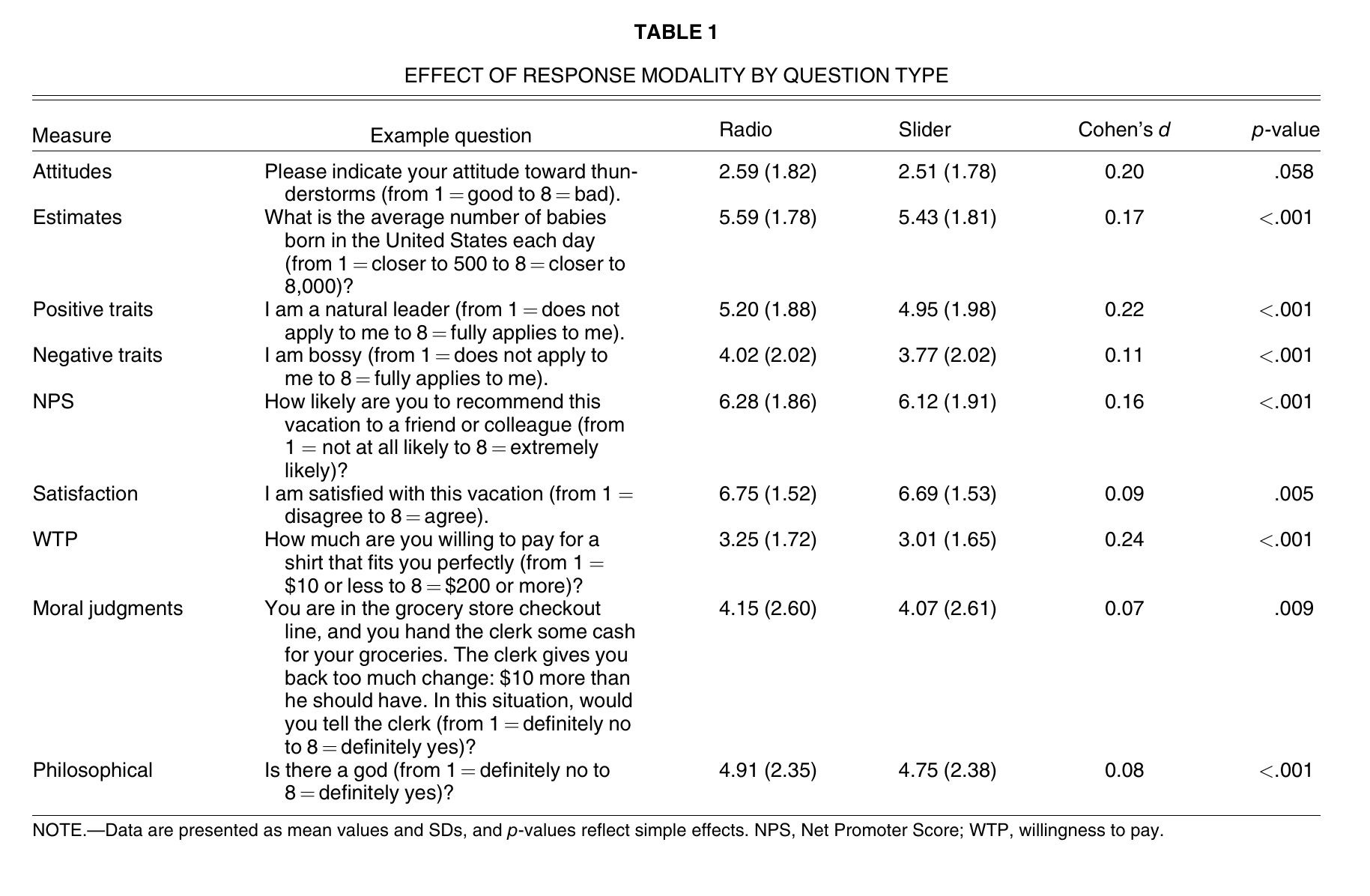

We test our hypotheses across six studies, as well as four additional studies reported in the web appendix. Study 1 documents the basic effect that using a slider (vs. clicking a radio button) produces responses that are closer to the starting point in nine different decision and judgment con texts, including personality ratings, numerical estimates, moral judgments, WTP, attitudes, consumer satisfaction, and philosophical standing. Study 2 finds that the effect of the slider is reversed (i.e., slider scales produce responses that are closer to the right endpoint) if participants begin at the right side of the scale and drag the cursor past progres sively lower values. Study 3 rules out an alternative explan ation that the effect is due to the perceived magnitude between response options differing by scale types by test ing the effect of slider versus radio-button scales with nom inal options that contain no magnitude. Studies 4 and 5 demonstrate the determining role of physical movement for our effect and use response time to capture different judg ment processes. Study 4 measures whether people click or drag the slider and finds the slider only results in lower responses when respondents drag it. Study 5 manipulates the physical movements participants make when using the slider scale and finds participants required to drag a slider provide responses closer to the starting point than those required to click a slider. Both studies 4 and 5 also measure response time. Consistent with our proposition that people using a slider interact with the scale before making a judg ment but those using a radio button interact with the scale after making a judgment, we find people who drag the slider exhibit faster initial click-down response times than those who click a radio button. Last, study 6 directly tests attention by capturing the eye gaze of participants using radio-button and slider scales. Participants dragging a slider scale attend to earlier options relatively more than later options on the scale than participants clicking a radio button. All our data and code are available at https:// researchbox.org/733.

Our studies capture the responses of 22,722 unique par ticipants and leverage a diverse range of contexts, from market research questions to philosophical standing. Across our studies, we identify a stable and robust effect of response kinesthetics: dragging a slider to a response reli ably yields responses closer to the scale starting point than clicking a radio button. On average, changing the response modality yields an effect size of Cohen’s d of 0.154 and a 95% confidence interval [CI] of [0.128–0.179]. Although this effect size is admittedly small, it can be managerially significant at scale. Every day, millions of consumers use online response scales to complete customer satisfaction surveys, make donations, and provide product reviews. For example, on the popular Qualtrics survey platform, approx imately 1.5 billion surveys have used radio buttons and 120 million surveys have used slider scales since the company’s inception (personal communication). 1 Our research sug gests the physical movements people use in their responses can affect these important and frequent business outcomes (see “General Discussion” section). Beyond the managerial applications of our specific empirical context, our work is a call to action for researchers to further explore how (seem ingly trivial) consumers’ physical movements when mak ing choices can meaningfully change the underlying psychological process of response.

STUDY 1: THE EFFECT OF KINESTHETIC PROPERTIES ON JUDGMENT

In study 1, participants used either a slider or radio but

ton to respond to various questions. We expected that using

a slider would result in responses that were closer to the

scale starting point (hypothesis 1).

Method

Study 1 used a two-condition (response modality: radio button vs. slider), between-subjects design. We collected data in three waves on Amazon Mechanical Turk (wave 1: N=1,991, M age =34.7,SD=11.7,1099woman;wave 2:N=1,964, M age =35.2,SD=11.7,1033woman;wave 3:N=2,021, M age = 34.8, SD=11.4,1138 women), which resulted in 5,426 unique participants (M age =34.8, SD = 11.5, 3,002 women). Participants were required to be on a laptop or desktop computer to be eligible for this and all subsequent studies. In each wave, participants responded to various blocks of question types, with both block order and questions within blocks randomized (see web appendix A for the list of stimuli and table 1for the results by question type). We collected data across multiple waves to limit the number of questions asked at any one time and to avoid fatigue. We collapsed across waves for ease of interpreta tion. Half the participants indicated their answer to ques tions by clicking on a typical radio-button scale; the other half indicated their answer using a slider scale.

To ensure that the only meaningful difference in these two conditions was the physical action used to indicate a response, we first restricted the slider scale to discrete val ues such that both conditions required participants to select a designated integer from 1 to 8. We then anchored both scales on a nonoption of “0” and informed participants that “0” was a holding place and that they would need to select another option to move forward in the survey. In subse quent studies, we instead provided a blank option as a hold ing place/anchor to demonstrate generalizability across different labels. In all studies, these nonoptions were pro hibited responses—participants could not advance to the next page until they selected a valid response. With this design, the primary difference between conditions is the kinesthetics of the response: in one condition, participants can drag a slider past other options to their response, and in the other condition, participants navigate their cursor directly to their response.

Results

To test the effect of the kinesthetic properties of a response scale on judgments, we ran a linear mixed-effects regression using the lmerTest package in R (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, and Christensen 2017) with response value as the dependent variable, response modality (radio vs. slider) as the independent variable, and participant, measure type, and question as random intercepts. Supporting hypothesis 1, participants who used a slider scale to indicate a response (M¼4.75, SD¼2.41) provided significantly lower values than participants who clicked a radio-button scale (M¼4.95, SD¼2.39; b¼−0.16, standard error [SE] ¼0.02, t(8,233) ¼−9.66, p <.001) across all tasks (table 1). Importantly, despite its small size, the effect of response modality was robust to question type. We ran a linear mixed-effects regression with response value as the dependent variable, response modality (radio button vs. slider), question type (e.g., WTP), and their interaction as the independent variables, with participant as the random intercept. We then used dummy coding to examine the sim ple effect of response modality on each question type. We found that the simple effect of condition is significant for all measures except attitudes (p ¼ .058), which still exhib ited the same directional difference. For this and all follow ing studies with repeated measures, we calculated effect size by first computing the mean and SD across items for the slider and the radio button and then using the psych package in R (Revelle 2024) to output Cohen’s d.

Discussion

In this study, we find that responding with a slider yields responses that are lower in value than when clicking a radio button across a wide array of question contexts, from moral judgments to WTP. In web appendix B, we replicate these results in an incentive-compatible context. We argue that our effect occurs because participants consider options as they drag past each one on the slider, which directs their attention to that option and therefore increases its chance of being selected. This process predicts that when the slider is anchored on the right side of the scale, rather than the left, the effect will flip—dragging the slider should result in higher values than clicking a radio button (i.e., closer to the right endpoint), because dragging a slider should bias attention to the right side of the scale. In study 2, we test this prediction by manipulating the starting point of the scale.

Click to read more