The October 2025 update of the WTO’s “Global Trade Outlook and Statistics” presents the WTO Secretariat’s revised forecasts for world trade in 2025 and 2026. Breakdowns of merchandise and commercial services trade by sector and region are provided, together with details on leading traders.

An analytical chapter looks at the limits of trade policy in influencing trade imbalances. The report is timed to coincide with the release of the WTO’s latest quarterly and annual trade statistics, which can be downloaded from the WTO’s online database at stats.wto.org

Published in 2025

Executive summary

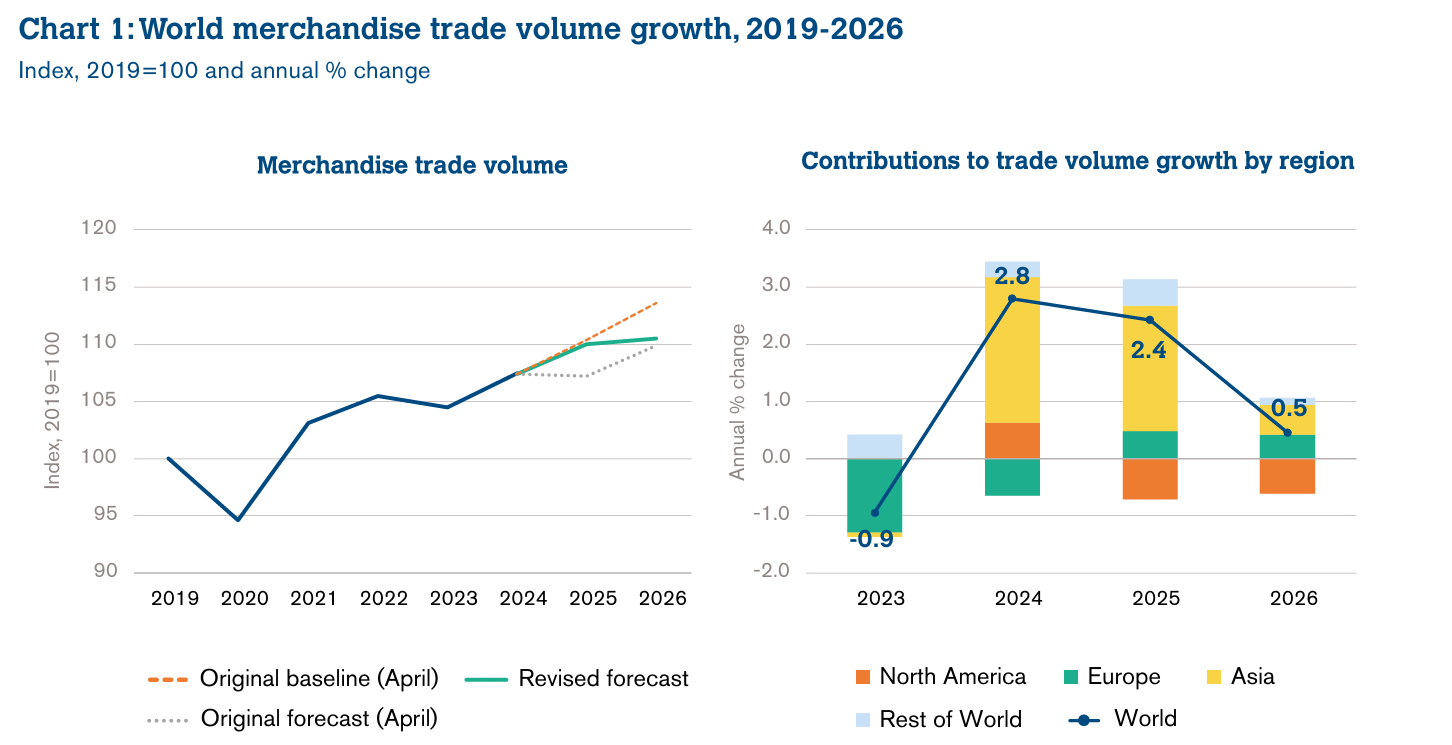

2 WTO economists’ forecast for world merchandise trade volume growth in 2025 has risen to 2.4% (up from the estimate of 0.9% in the interim outlook in August) while the outlook for 2026 has deteriorated to 0.5% (down from the August estimate of 1.8%).

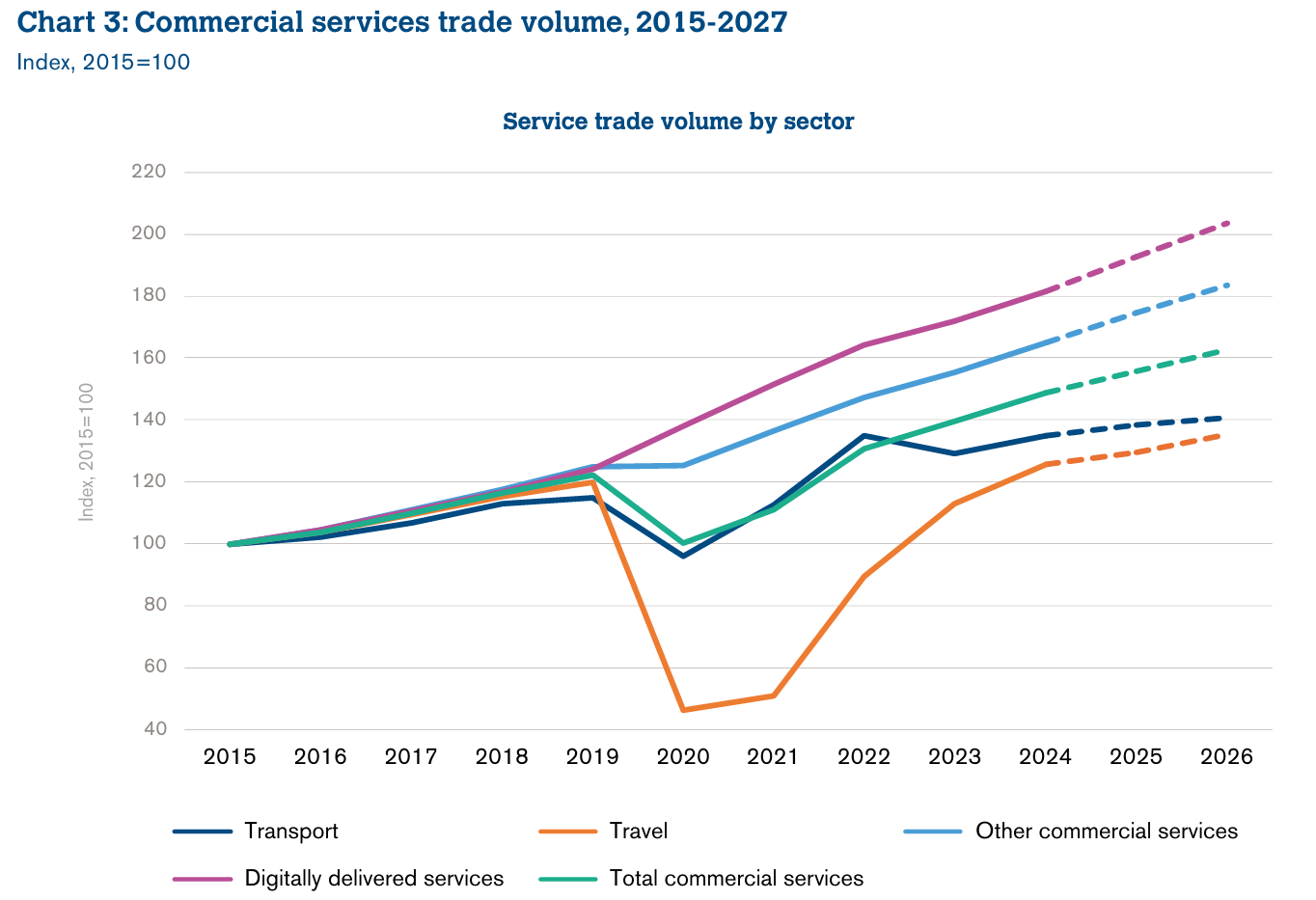

The forecast for services trade has also been updated, with commercial services export volume now expected to grow 4.6% in 2025 and 4.4% in 2026, up slightly from the previous estimates last April.

The volume of world merchandise trade was up 4.9% year-on-year in the first half of 2025, growing at a faster rate than expected. Several factors contributed to this robust trade expansion, including frontloading of imports in North America in anticipation of higher tariffs, favourable macroeconomic conditions (e.g. disinflation, supportive fiscal policies, strong growth in emerging markets) and a surge in demand for AI-related goods.

It is difficult to determine how much of the boost to trade in the first half of the year was due to macroeconomic “push” factors but the April edition of Global Trade Outlook and Statistics noted that, if it were not for higher tariffs and rising policy uncertainty, macroeconomic conditions were expected to be supportive of trade growth in 2025.

Prospects for the second half of 2025 and 2026 are less optimistic. With higher tariffs now in place and trade policy still highly uncertain, frontloading of purchases is expected to unwind as accumulated inventories are drawn down and as GDP growth slows. Possible signs of weakness in trade and manufacturing output have been observed in developed economies, including reduced business and consumer confidence and slower growth in employment and incomes.

As a result, the new forecast indicates stronger trade growth in 2025 and weaker trade growth in 2026. For 2025 and 2026 combined the forecast is slightly stronger in the current forecast (+2.9%) than in the previous one (+2.3%).

The US$ value of world merchandise trade was up 6% year-on-year in the first half of 2025. In contrast to goods, year-on-year growth in commercial services trade slowed to 5% in the first quarter of this year from 10% in the final quarter of last year but appears to have bounced back to 9% in the second quarter based on preliminary data.

The analytical section on the role of trade policy in influencing trade imbalances examines how trade balances respond to policy interventions, such as tariffs and macroeconomic policies.

Trade resilient despite tariff increases but growth to slow next year

Outlook for world trade in 2025 and 2026

Global merchandise trade grew faster than expected in the first half of 2025 as US imports surged ahead of expected tariff hikes and as spending on AI-related products accelerated, particularly in Asia and North America. In response, WTO economists have revised their trade projections for this year and next year (see Chart 1), upgrading their forecast for world merchandise trade volume growth in 2025 to 2.4% (up from 0.9% in the August forecast) and lowering their estimate for 2026 to 0.5% (down from the previous forecast of 1.8%).

In addition to frontloading of purchases and AI-related spending, trade in 2025 was also supported by favourable macroeconomic conditions, as disinflation, supportive fiscal policies and tight labour markets with high demand for workers boosted real incomes and spending in major economies. Trade growth is expected to slow in 2026 as the global economy cools and as the full impact of higher tariffs is finally felt for a full year.

The WTO’s forecast for world commercial services trade in volume terms has also been revised in light of recent developments. Although not directly subject to tariffs, services trade can be affected indirectly through links to goods trade and output. Services export growth is now expected to slow from 6.8% in 2024 to 4.6% in 2025, and down to 4.4% in 2026. These estimates are slightly stronger than the WTO’s adjusted forecast in April, which took account of the impact of tariff increases, and slightly weaker than the April baseline forecast that excluded their influence.

Note: Trade refers to average of exports and imports. Figures for 2025 and 2026 are projections.

Sources: WTO for historical trade statistics. WTO Secretariat estimates for trade forecasts.

Merchandise trade

The volume of world merchandise trade, as measured by the average of exports and imports, recorded a sharp 5.5% year-on-year increase in the first quarter of 2025 followed by a smaller 4.3% rise in the second quarter, leaving trade in the first half of the year up 4.9% compared to the same period in 2024.

The strong performance in the first half of the year boosted WTO economists’ tariff-adjusted merchandise trade growth forecast in 2025 to 2.4%, well above the adjusted forecast of -0.2% for 2025 in the April 2025 edition of Global Trade Outlook and Statistics (see Chart 1). On the other hand, the new adjusted forecast for 2026 of 0.5% is considerably weaker than the 2.5% foreseen in April. As a result, the cumulative increase for 2025-26 is only slightly stronger in the current forecast (+2.9%) than in the previous one (+2.3%), suggesting that the full impact of higher tariffs may have been delayed until next year.

Despite a strong first half of 2025, North American trade flows are expected to make a negative contribution to world merchandise trade growth for the whole of 2025 and in 2026. Asia is expected to make the largest positive contribution to trade growth this year, although it will be reduced next year. Finally, Europe and the rest of the world should both make modest positive contributions to trade expansion in both years.

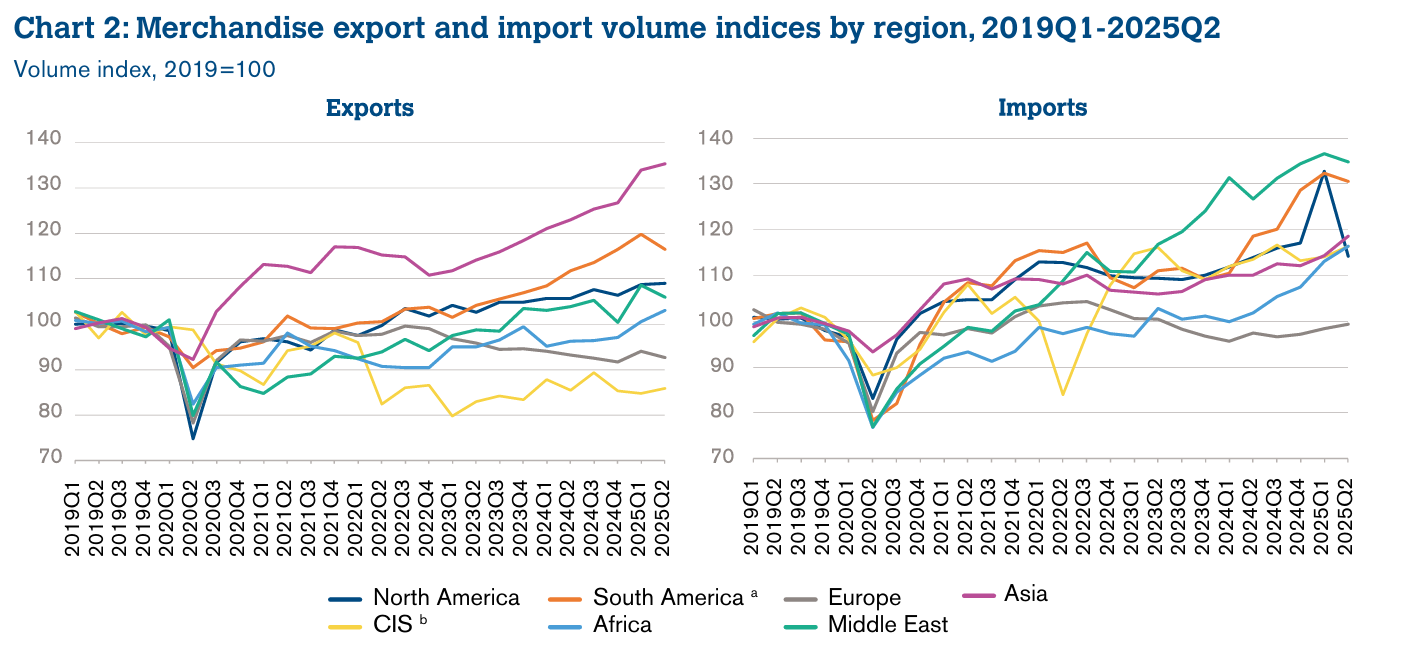

Year-on-year growth in merchandise export volume for the first half of 2025 was positive in most WTO regions, with Asia leading growth at 10.4% (see Chart 2). North America experienced slower growth at 3.0%, including a 2.2% increase in the first quarter. Europe remained relatively flat with a 0.3% decrease in growth. Both South and Central America and the Caribbean (7.4%) and Africa (6.3%) had moderately high growth in merchandise exports. The Middle East region grew at 3.7%. The only region with a notable decrease in merchandise exports was the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), including certain associate and former member states, with a 1.5% decrease.

On the import side, all regions experienced positive year-on-year growth for the first half of 2025. South America (14.7%) and Africa (13.7%) led growth, followed by North America (9.4%), despite the latter’s sharp 13.9% decrease in import volume between the first and second quarters. Asia (5.8%) and the Middle East (5.1%) had more moderate import volume growth in the first half of the year, and Europe (2.4%) and the CIS (2.2%) had the slowest growth. Quarter-on-quarter import growth was generally weaker in the second quarter of 2025 except for Asia, where the second quarter was stronger than the first.

a Refers to South and Central America and the Caribbean.

b Refers to Commonwealth of Independent States, including certain associate and former member states.

Source: WTO-UNCTAD.

Commercial services

GLOBAL TRADE OUTLOOK AND STATISTICS - UPDATE: OCTOBER 2025 Taking into account current GDP and merchandise trade forecasts reflecting the influence of higher tariffs, growth in the volume of world commercial services trade (as measured by exports) is expected to slow to 4.6% in 2025 and to 4.4% in 2026, down from 6.8% in 2024 (see Chart 3). The reduced outlook for 2025 reflects weaker expected growth in transport (2.5%, down from 4.5% in 2024) and travel (3.1%, down from 11% last year). Growth in the category “other commercial services” should only be slightly weaker in 2025 than in 2024 (5.8% compared to 6.3%) but digitally delivered services should be marginally stronger (6.1% compared to 5.7%).

For 2026, growth in transport services is expected to be slower at 1.8%, reflecting the deteriorating outlook for merchandise trade. Meanwhile, travel growth should pick up slightly to 4.4%, while growth should remain mostly stable for “other commercial services” (5.1%) and digitally delivered services (5.6%).

Macroeconomic conditions

Macroeconomic developments were more positive in the first half of the year than initially expected in April 2025 due to a higher level of international trade and investment in key regions. This was principally driven by the larger-than-expected frontloading of purchases by firms and households in anticipation of future tariff increases.

In the first quarter of the year, imports surged in North America, matched by rising exports in the rest of the world. Industry reports have indicated a build-up in inventories, including in purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) and national statistics. Inventories-to-sales ratios were up in North America in several sectors, including machinery, equipment and supplies, motor vehicles and parts, lumber and construction equipment, and non-durable goods purchases by wholesalers.

Note: Trade refers to exports. Figures for 2025 and 2026 are projections.

Source: WTO Secretariat estimates.

Around one-third of the North American import spike was due to inflows of precious metals while the remainder was related to other goods, mainly electronics (including parts) and chemicals (mostly pharmaceuticals originating in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and European economies). In parallel, EU imports from North America rose in March, suggesting that firms operating supply chains across the Atlantic also increased their inventories, particularly in the pharmaceuticals sector.

Some of the factors that boosted GDP in the first quarter (Q1) receded in the second quarter, but not entirely. The contribution of inventories to GDP growth in North America turned negative in Q2 while investment overtook consumption as a driver of GDP. In Asia, second quarter GDP slowed compared to the previous period yet still exceeded expectations in key economies (such as China, Japan, Viet Nam and Thailand). Eurozone growth also showed signs of resilience. Inventory building and port activity remained strong in July ahead of the August tariff announcements. This lifted industrial activity, indicating a forward-looking response to trade policy changes.

Disentangling the exact amount of the windfall to output and trade from the frontloading of purchases as opposed to other macroeconomic “push” factors during this period is challenging. As highlighted in the April 2025 edition of Global Trade Outlook and Statistics, macroeconomic conditions, in the absence of restrictive and uncertain trade policies, had been expected to be supportive of trade.

In several parts of the world, multiple factors have contributed to a resilient macroeconomic environment. A combination of falling headline inflation, supportive fiscal policy and tight labour markets boosted real incomes. Regional factors also contributed to a catch-up in aggregate demand in Europe following two years where high energy prices depressed industrial activity and investment. Asia’s export performance was strong, particularly in AI-related products, consistent with the worldwide surge in investment in this sector.

Prospects for the second half of the year are less optimistic. With higher tariff rates and increased trade policy uncertainty, frontloading of purchases is expected to eventually unwind, although it is unclear whether the downward correction will be exactly equivalent to the “windfall”. Box 1 examines the academic literature on the relationship between trade and inventories in uncertain times. According to this research, returning to desired levels of inventories can take several months. Export-oriented economies are expected to see a reduction in demand, while reduced business and household consumer confidence will affect purchasing decisions.

Several indicators, including prices of inputs in production and slower trade shipments, suggest that inflation could pick up in the second half of 2025 as inventories are drawn down in economies and sectors where tariffs have been increased and supply chain exposure is high. The initial reaction to tariffs was a period of price absorption and reduced profits by firms. Typically, economic models predict a “pass-through” of tariffs to final goods prices.

To date, it appears that domestic firms have absorbed part of the cost of already imposed tariff increases, at least through July. Cavallo et al. (2025) found “that the tariff announcements led to rapid, though still moderate, price increases”. Other sources point to a moderate price reaction by firms in order to preserve buyer-supplier relationships at the cost of eroding profit margins. A departure from the disinflation trend since the start of the year could affect consumer and investment sentiment and behaviour. Lower profit margins could contribute to a sustained slowdown in fixed investment.

Cooling global aggregate demand will eventually translate into slower trade growth. With the full effect of higher tariffs taking place in August, some of the impact described in the April 2025 edition of Global Trade Outlook and Statistics will be delayed to the latter part of 2025 and into 2026.

Click to read more