Key Findings

- 1. Nearly all K–12 schools had a cell phone policy that allowed students to bring their phones to school during the 2024–2025 school year, but two-thirds of schools had a policy that prohibited cell phone use from “bell to bell.”

- 2. Eighty-six percent of principals in schools with some sort of policy restricting cell phone use endorsed the safety-related benefits of those policies, most commonly citing positive impacts on school climate, a reduction in inappropriate cell phone use, and a reduction in cyberbullying.

- 3. Although six in ten youth supported some restrictions on cell phone use during classes, only one in ten supported bell-to-bell policies.

- 4. Those youth who supported policies prohibiting cell phone use during classes did so because they said that such policies reduce distractions.

Cell phones are overwhelming K–12 schools. Teachers are pushing for cell phones to be removed from schools, citing constant disruptions to classroom instruction and concerns about what responsibility they might have for the content that students post while in their classrooms (Hatfield, 2024; Langreo, 2023; Walker, 2025). School administrators are worried that cell phones have negatively affected students’ academic learning, mental health, and attention spans (National Center for Education Statistics, 2025). Beyond the impacts of cell phone use on student learning and mental health, cell phone and social media use have created a rash of safety problems for schools, including cyberbullying and threats (Moore et al., 2024; Vogels, 2022).

Because of growing concerns about students’ overreliance on cell phones in schools and disruptions to students’ learning, there has been a growing effort to curb students’ cell phone use while at school. As of June 2025, 29 states have passed legislation restricting cell phone use in K–12 schools (Ballotpedia, undated), and many school districts in states with and without state-level policies have enacted their own cell phone policies. In fact, in a survey administered to school districts in spring 2025, nine in ten said that they now have some form of a cell phone policy (Grant et al., 2025).

Yet despite the recent proliferation of restrictive cell phone policies in schools, there are fewer national data to date on how such policies play out in schools across the United States. To provide a first glimpse of K–12 educator and youth reactions to these policies and some details about their implementation, we used survey panels to ask principals and youth about their experiences with cell phone policies in K–12 schools. We conducted multiple nationally representative surveys over the course of the 2024–2025 school year and compiled the results in this report.

In our analyses of educators’ perceptions of cell phone policies, we focused on safety-related benefits, because other recent national surveys had already examined educators’ perceptions of how cell phones and related policies affect student learning, mental health, and attention (e.g., Hatfield 2024; National Center for Education Statistics, 2025). More details about the specific surveys we analyze in this report can be found in the “Methodology” section. We intend to field questions annually using our survey panels to learn to what extent educator and youth attitudes about cell phone policies shift over time. This report is intended for school system leaders who may still be considering enacting cell phone policies in their schools and want to learn what other schools across the United States are doing.

Altogether, our survey results show that, most commonly, schools have a policy prohibiting cell phone use from bell to bell—students can bring their cell phones to school but cannot use their cell phones during the school day. Although principals overwhelmingly perceive cell phone policies as having many positive benefits, youth generally support lighter rather than heavier restrictions on cell phone use.

According to Principal Reports, Schools’ Policies Typically Allow Students to Bring Cell Phones to School but Prohibit Their Use from Bell to Bell

We asked a nationally representative sample of principals in October 2024 what their school’s cell phone policy was for the 2024–2025 school year. Echoing results from a 2025 federal survey (National Center for Education Statistics, 2025), nearly all principals (95 percent) said that their schools allowed students to bring cell phones to school. But most schools’ policies placed restrictions on where and when students could use their cell phones (see Figure 1). More specifically, 67 percent of principals said that their schools had a bell-to-bell policy, which allowed students to have cell phones at school but prohibited cell phone use when school was in session. Meanwhile, 16 percent of principals said that their schools’ policy allowed students to use cell phones only during lunch or hallway transition time, and 9 percent of principals said that their schools allowed cell phone use during class time at the teacher’s discretion. However, simply because a school had a specific policy in place does not mean that all educators enforced that policy or that all students complied with that policy (Hatfield, 2024; Prothero, 2024).

Figure 1. Percentage of Principals Reporting That Their School Has a Cell Phone Policy

NOTE: This figure depicts response data from the following survey question administered to a nationally representative sample of K–12 school principals in October and November 2024: “What is your school’s cell phone policy this year (2024–25)?” (n = 955). We excluded responses from 3 percent of principals who said that they had “other” policies.

High Schools Were Less Restrictive About Cell Phones Than Elementary and Middle Schools

During the 2024–2025 school year, approximately four of five elementary and middle schools had a bell-to-bell policy, which stipulated that all cell phone use was prohibited during the entire school day (see Figure 2). High schools, however, tended to have more-lenient policies. About one-half of high schools allowed students to use their cell phones when class was not in session (e.g., during lunch or hallway transition time) but not during class time. One-quarter of high schools allowed students to sometimes use cell phones during class time at the teacher’s discretion.

Figure 2. Percentage of Schools with Cell Phone Policies, by Grade Level

NOTE: This figure depicts response data from the following survey question administered to a nationally representative sample of K–12 school principals in October and November 2024: “What is your school’s cell phone policy this year (2024–25)?” (n = 927). We excluded responses from 3 percent of principals who said that their schools had “other” policies. An asterisk (*) indicates that the percentage of secondary (middle or high school) principals who reported that their school has a specific type of cell phone policy is statistically significantly different from the percentage of elementary principals who responded similarly.

Principals Strongly Endorsed the Safety-Related Benefits of Cell Phone Policies

We asked a separate nationally representative sample of K–12 school principals the following question in October 2024: “What are the school safety–related benefits or drawbacks of the student cell phone ban in place at your school?”[1] (In this survey, principals were not asked to provide more details about which specific restrictions the cell phone policy placed on students’ cell phone use, whether during class time or throughout the school day; therefore, the term ban is used loosely with respect to this survey.) As part of this question, we listed a variety of possible benefits and drawbacks that might be associated with such policies at their schools and asked principals which, if any, benefits and drawbacks applied to their schools (see Figure 3).

Principals overwhelmingly perceived their cell phone policies as a benefit to school safety. Eighty-six percent of principals said that their policy offered school safety–related benefits, including 59 percent who said that their policy resulted in only benefits to school safety and 26 percent who said that their policy resulted in a mix of benefits and drawbacks to school safety. The most-common benefits that principals reported were positive impacts on school climate (70 percent of principals), a reduction in inappropriate cell phone use (67 percent of principals), and a reduction in cyberbullying (54 percent of principals). Conversely, the most-common drawbacks that principals reported were concerns among parents (21 percent of principals) and students (10 percent of principals) about not having direct access to each other, including during an emergency.

Figure 3. Percentage of Principals Reporting School Safety–Related Benefits or Drawbacks of Cell Phone Policies

NOTE: This figure depicts response data from the following survey question administered to a nationally representative sample of K–12 school principals in October 2024: “What are the school safety–related benefits or drawbacks of the student cell phone ban in place at your school?” (n = 501). In their responses, principals were instructed to select all answers that applied. Only principals who reported having a cell phone ban in place for students at their school saw this question. The response option “The cell phone ban does not have an impact on school safety at my school” was selected by 13 percent of principals; this response option is not included in the figure.

Secondary School Principals Were More Likely Than Elementary School Principals to Report Safety-Related Benefits from Cell Phone Restrictions

Middle and high school principals were especially likely to identify benefits from cell phone use bans (see Figure 4). Relative to their elementary school counterparts, secondary school principals were more likely to cite positive impacts on school climate, a reduction in inappropriate cell phone use, and a decrease in cyberbullying. Middle school principals were also more likely to identify additional benefits, such as a reduction in the use of cell phones to make threats and lower levels of student distraction during safety drills or emergencies.

Even though middle school principals were particularly likely to report benefits, they were also the most likely to identify increased concern among parents about their lack of direct access to their children during an emergency. Conversely, high school principals reported the greatest levels of concern among students about increased anxiety from not being able to contact their parents.

Figure 4. Percentage of Principals Reporting School Safety–Related Benefits or Drawbacks of Cell Phone Bans, by Grade Level

NOTE: This figure depicts response data from the following survey question administered to a nationally representative sample of K–12 school principals in October 2024: “What are the school safety–related benefits or drawbacks of the student cell phone ban in place at your school?” (n = 492). In their responses, principals were instructed to select all answers that applied. Only principals who reported having cell phone bans in place for students at their schools saw this question. The response option “The cell phone ban does not have an impact on school safety at my school” was selected by 19 percent of elementary school principals, 5 percent of middle school principals, and 5 percent of high school principals; this response option is not included in the figure. An asterisk (*) indicates that the percentage of middle or high school principals who selected a specific benefit or drawback is statistically significantly different from the percentage of elementary principals who responded similarly.

Although Six in Ten Youth Supported Some Restrictions on Cell Phone Use During Class, Only One in Ten Supported a Bell-to-Bell Policy

Emerging research suggests that youth are more skeptical of policies that put stronger restrictions on their cell phone use than their parents and educators (Aldis, 2024). To provide more insight on this point, in winter 2025, we asked a nationally representative sample of youth ages 12 to 21 who are members of the RAND American Youth Panel (AYP) how they felt about various cell phone use policies. Only AYP panel members who reported being enrolled in K–12 schools were asked about their schools’ cell phone policies. The vast majority of youth who received these questions were between the ages of 12 and 17, but a small portion of older youth were still enrolled in K–12 schools.

We found that, although youth were skeptical of blanket bell-to-bell policies prohibiting cell phone use during the entire school day, many youth did support at least some degree of cell phone use restriction. More specifically, 60 percent of youth enrolled in K–12 schools were supportive of some cell phone use restrictions during the school day (see Figure 5). Only 11 percent of youth said that cell phone use should be prohibited bell to bell. Although middle school grade youth and high school grade youth reported similar levels of comfort with some rules on cell phone use during the school day, younger youth were more supportive of more-restrictive practices. For example, the idea of storing cell phones in safe lockers was twice as popular among middle school grade youth than among high school grade youth. Conversely, high school grade youth were slightly more likely to report that phones should be prohibited in class only sometimes.

These results largely align with what principals reported as their schools’ policies; that is, restrictions on cell phone use in class are more common for younger students (see Figure 2).

Figure 5. Percentage of Youth (Ages 12–21) Enrolled in K–12 Schools Who Support Cell Phone Policies in Some Form

NOTE: This figure depicts response data from the following survey questions administered to a nationally representative sample of youth ages 12 to 21 in January and February 2025: “Should [grade level] schools ban cell phones from the entire school day? This would include during lunch, class time, and between classes” and “Should [grade level] schools ban cell phones from classes?” (n = 1,270). Only youth who said that they were enrolled in K–12 public and private schools received this question. K–12 students who said that they were homeschooled only received this question if they took classes with students outside their family. The response options have been truncated for readability. An asterisk (*) indicates that the percentage of high school youth (i.e., those enrolled in grades 9 through 12) who supported a specific cell phone policy is statistically significantly different from the percentage of middle school youth (i.e., those enrolled in grades 5 through 8) who responded similarly.

The Main Reason Youth Supported Policies Prohibiting Cell Phone Use in Class Was to Reduce Distractions

We asked youth for their reason(s) for supporting or opposing policies prohibiting cell phone use during class. (We did not ask a similar question of youth who supported or opposed bell-to-bell policies prohibiting use for the entire school day.)

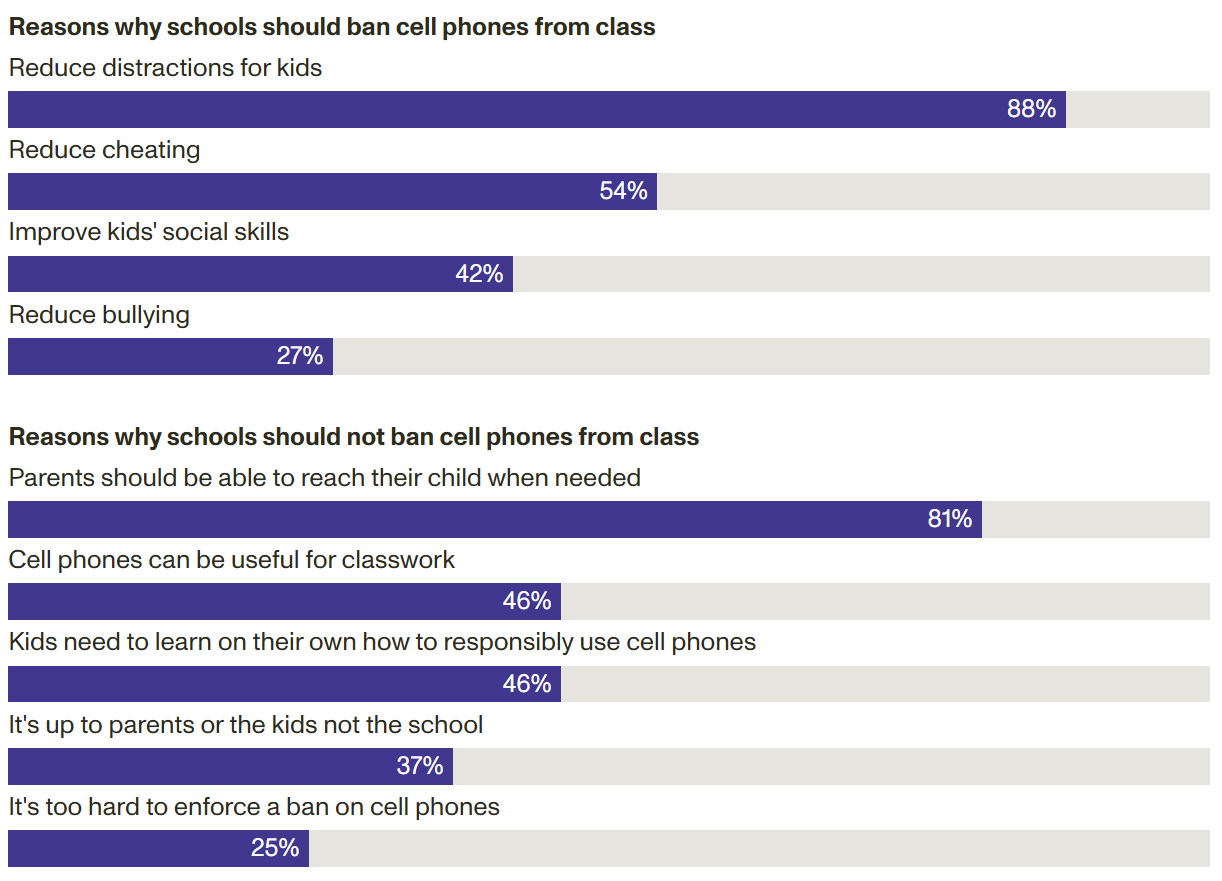

An overwhelming 88 percent of youth named reducing distractions as their reason for supporting policies that prohibit cell phone use during class time (see Figure 6). Reducing distractions beat out other reasons, such as reducing cheating, improving social skills, and reducing bullying. Relatively few youth identified reductions in cyberbullying as a reason to support such policies, even though more than one-half of principals identified this reason as a main benefit (see Figure 3).

There was also a clear top reason why youth reported that schools should not prohibit cell phone use in class: 81 percent of youth who were against such policies said that their parents should be able to reach them when needed. Adults who were surveyed also named this as their number one reason for opposing more-restrictive cell phone policies (Anderson, Gottfried, and Park, 2024).

The reasoning among youth for supporting or opposing cell phone policies that prohibit use during class time did not differ on the basis of age. That is, similar percentages of middle school grade youth and high school grade youth selected each reason for supporting or opposing such policies. There was one exception: High school grade youth were 10 percentage points more likely than their middle school grade counterparts to say that it is too hard to enforce a ban on cell phones.

Figure 6. Percentage of Youth (Ages 12–21) in K–12 Schools Who Selected Reasons Why Schools Should or Should Not Prohibit Cell Phones in Class

NOTE: This figure depicts response data from the following survey questions administered to a nationally representative sample of youth ages 12 to 21 in January and February 2025: “Why should schools ban cell phones from classes?” and “Why shouldn’t schools ban cell phones from class?” (n = 1,199). Only youth who said that they were enrolled in K–12 public and private schools received this question. K–12 students who said that they were homeschooled only received this question if they took at least some in-person classes with students outside their family. Youth were asked only about their reasons for supporting (n = 756) or opposing cell phone bans (n = 443) during class on the basis of their indicated preference.

Summary

The debate over cell phone policies in schools reveals a complex balancing act between ensuring school safety and reducing distractions to keep students focused on learning. At the same time, schools must find ways to maintain communication between students and their families. The near ubiquity of cell phones in students’ lives and the growing role that technology plays in the classroom further complicate these issues.

The data we gathered from the survey panels suggest that principals largely view policies that restrict or prohibit students’ cell phone use as beneficial, citing reductions in cyberbullying and inappropriate phone use and benefits to school climate. Although many youth support some restrictions on cell phone use during class time, they generally remain skeptical of bell-to-bell policies that prohibit cell phone use during the entire school day. Students are especially concerned that such policies limit their ability to stay connected with their parents. There are indications that bell-to-bell policies also make parents nervous for the same reason and, in particular, that parents will not be able to reach their children in the event of an emergency (Chuck, 2024).

School leaders will need to grapple with these competing priorities and aim to strike the right balance as they craft cell phone policies that are age appropriate, enforceable, and responsive to the needs of both educators and students.

MethodologyData CollectionThis report uses data from three nationally representative surveys administered during the 2024–2025 school year. Two of these surveys were administered to the RAND American School Leader Panel (ASLP), a panel of approximately 8,000 K–12 school principals. The third survey was administered to members of the newly established American Youth Panel (AYP). More details about the two survey panels and the specific surveys administered to these panels are provided below. When available, we also reference RAND reports related to these surveys that offer more technical details. American School Leader PanelThe ASLP was established in 2014 and significantly expanded in 2018. The ASLP is refreshed annually to maintain a nationally representative panel of K–12 public school principals and to account for panel attrition. School leaders are recruited through probability-based methods using a list of principals obtained from MDR Education. For more information about how the ASLP was established, please see Robbins and Grant (2020). Panelists who are recruited to the ASLP have agreed to participate in online surveys several times per year, and they receive incentives for completing surveys. The analyses in this report rely on data from two surveys that were administered through the ASLP during the 2024–2025 school year. Samples for these two surveys were drawn independently using probability-based sampling methods; any overlap in the sampled panelists in these two surveys is incidental. American School Leader Panel Fall 2024 OmnibusThis survey was administered to a nationally representative sample of K–12 public school principals through the ASLP between October 21, 2024, and November 25, 2024. In total, 3,125 principals were sampled to complete the ten-minute survey, and 1,019 principals completed enough of the survey to receive a weight (a 33.1 percent completion rate). 2024 School Safety and Security School Leader SurveyThis survey was administered to a nationally representative sample of K–12 public school principals through the ASLP between October 17, 2024, and October 29, 2024. In total, 3,334 principals were sampled to complete the ten-minute survey, and 971 principals completed enough of the survey to receive a weight (a 29.8 percent completion rate). Both ASLP survey samples were independently weighted to make respondents representative of the national population of public school principals and the schools that they serve. Although we weighted our national samples of principals to make them representative of the national population of public school principals at least on such observable characteristics as gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, school level, school locale, school enrollment size, school racial/ethnic composition, and school neighborhood poverty level, even our weighted survey sample might not be entirely representative of principals nationally. It is likely that the public school principals who enroll in the ASLP and take our surveys differ from those who do not in meaningful ways that are impossible to observe and measure. The population data for public school principals are from the National Teacher and Principal Survey (2020–2021), the school characteristics are from the Common Core of Data (2022–2023), and the school neighborhood poverty estimates are from the EDGE School Neighborhood Poverty Estimates (2020–2021). All data collections were administered by the National Center for Education Statistics. American Youth PanelThe AYP was established in 2024 to augment the American Life Panel (ALP). Developed by RAND researchers in 2006, the ALP is a probability sample–based panel of approximately 10,000 adults in the United States ages 18 and older. The AYP includes a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized English-speaking youth in the United States between the ages of 12 and 21 whose parents (at least those who are ages 12 to 17) are members of the ALP. ALP parents give consent for their children who are minors to participate in the panel, and they are given the option to enroll one or more children ages 12 to 17. Youth who join the panel are asked to take periodic surveys about social, economic, and policy issues. As of August 2025, the AYP includes about 2,000 youth and is currently recruiting additional participants. For more details about how the AYP was established as an expansion of the ALP, see Schwartz et al. (2025). American Youth Panel Winter 2025 SurveyThe analyses we present in this report are from a survey administered to youth between January 21, 2025, and February 22, 2025, who are members of the AYP. In total, 520 AYP members ages 12 to 21 completed the survey. Multiple children from the same household were invited to participate in the survey if they were members of the AYP.[2] The small sample size is due to the fact that recruitment into the AYP was still taking place when the survey was administered. Therefore, we also administered the same survey to youth ages 12 to 17 whose parents are members of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel to increase the sample size. In total, 1,551 youth ages 12 to 21 completed surveys out of roughly 3,500 who were invited to do so. We weighted these 1,551 youth (combining the AYP and Ipsos samples) to make them representative of the national population of youth ages 12 to 21, at least with respect to observed characteristics, including sex, race/ethnicity, region, metropolitan status (a measure of locale), and enrollment status. Population distribution benchmarks for the weighting are from the 2023 American Community Survey. The questions that we analyzed in this report were administered to a subset of 1,270 youth, regardless of age, who told us in the survey that they were currently enrolled in K–12 public or private schools (or that they were homeschooled but took at least some classes with students outside their family). AnalysisAll survey estimates were produced using cross-sectional survey weights designed specifically to provide nationally representative estimates at the time when the survey was administered. Within each survey, we conducted significance testing to assess whether subgroups were statistically different at the p < 0.05 level. In the report, we describe only those differences among district subgroups that are statistically significant at the 5 percent level. Because of the exploratory nature of this study, we did not apply multiple hypothesis test corrections. |

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the educators and youth who agreed to participate in the survey panels. Their time and willingness to share their experiences were invaluable to this effort and to helping us understand how to better support work in schools. We thank Daniel Ibarrola, Brian Kim, and Sarah Ohls for helping manage the surveys; Gerald Hunter, Ruolin Lu, and Julie Newell for serving as the data managers for these surveys; and Tim Colvin, Roberto Guevara, and Julie Newell for programming these surveys. Thanks to Joshua Eagan, Dorothy Seaman, and Claude Messan Setodji for managing the sampling and weighting. We greatly appreciate the administrative support provided by Tina Petrossian. We also appreciate feedback from Julia Kaufman, who reviewed early drafts of this report. We thank Elizabeth Steiner and Brigette Whaley for helpful feedback that greatly improved this report. We also thank Valerie Bilgri for her editorial expertise and Monette Velasco for overseeing the publication process.

Notes

- [1] In this survey, principals were asked, “Does your school have a cell phone ban in place for students?” Fifty-three percent of principals reported having a cell phone ban in their schools.

[2] Of the 1,551 cases represented in the panel, 142 cases had another member of the household in the panel. Because of the small number of these cases (less than 10 percent), and because we conducted limited subgroup analyses with the youth data file, we did not cluster our standard errors at the household level.

References

- Anderson, Monica, Jeffrey Gottfried, and Eugenie Park, “Most Americans Back Cellphone Bans During Class, but Fewer Support All-Day Restrictions,” Pew Research Center, October 14, 2024.

- Ballotpedia, “State Policies on Cellphone Use in K-12 Public Schools,” webpage, undated. As of June 29, 2025:

https://ballotpedia.org/State_policies_on_cellphone_use_in_K-12_public_schools - Grant, David, A. K. Keskin, Melissa Kay Diliberti, Claude Messan Setodji, Gerald P. Hunter, Samantha E. Dinicola, and Heather L. Schwartz, Technical Documentation for the Eleventh American School District Panel Survey, RAND Corporation, RR-A956-37, 2025. As of September 5, 2025:

https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-37.html - Hatfield, Jenn, “72% of U.S. High School Teachers Say Cellphone Distraction Is a Major Problem in the Classroom,” Pew Research Center, June 12, 2024.

- Langreo, Lauraine, “Cellphone Bans Can Ease Students’ Stress and Anxiety, Educators Say,” Education Week, October 16, 2023.

- Moore, Pauline, Brian A. Jackson, Jennifer T. Leschitz, Nazia Wolters, Thomas Goode, Melissa Kay Diliberti, and Phoebe Felicia Pham, Developing Practical Responses to Social Media Threats Against K–12 Schools: An Overview of Trends, Challenges, and Current Approaches, RAND Corporation, RR-A1077-5, 2024. As of June 29, 2025:

https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1077-5.html - National Center for Education Statistics, “More Than Half of Public School Leaders Say Cell Phones Hurt Academic Performance,” press release, February 19, 2025.

- Prothero, Arianna, “How Students Are Dodging Cellphone Restrictions,” Education Week, November 11, 2024.

- Robbins, Michael W., and David Grant, RAND American Educator Panels Technical Description, RAND Corporation, RR-3104-BMGF, 2020. As of July 25, 2025:

https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3104.html - Schwartz, Heather L., Robert Bozick, Melissa Kay Diliberti, and Sarah Ohls, Students Lose Interest in Math: Findings from the American Youth Panel, RAND Corporation, RR-A3988-1, 2025. As of August 4, 2025:

https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3988-1.html - Vogels, Emily A., “Teens and Cyberbullying 2022,” Pew Research Center, December 15, 2022.

- Walker, Tim, “Take Cellphone