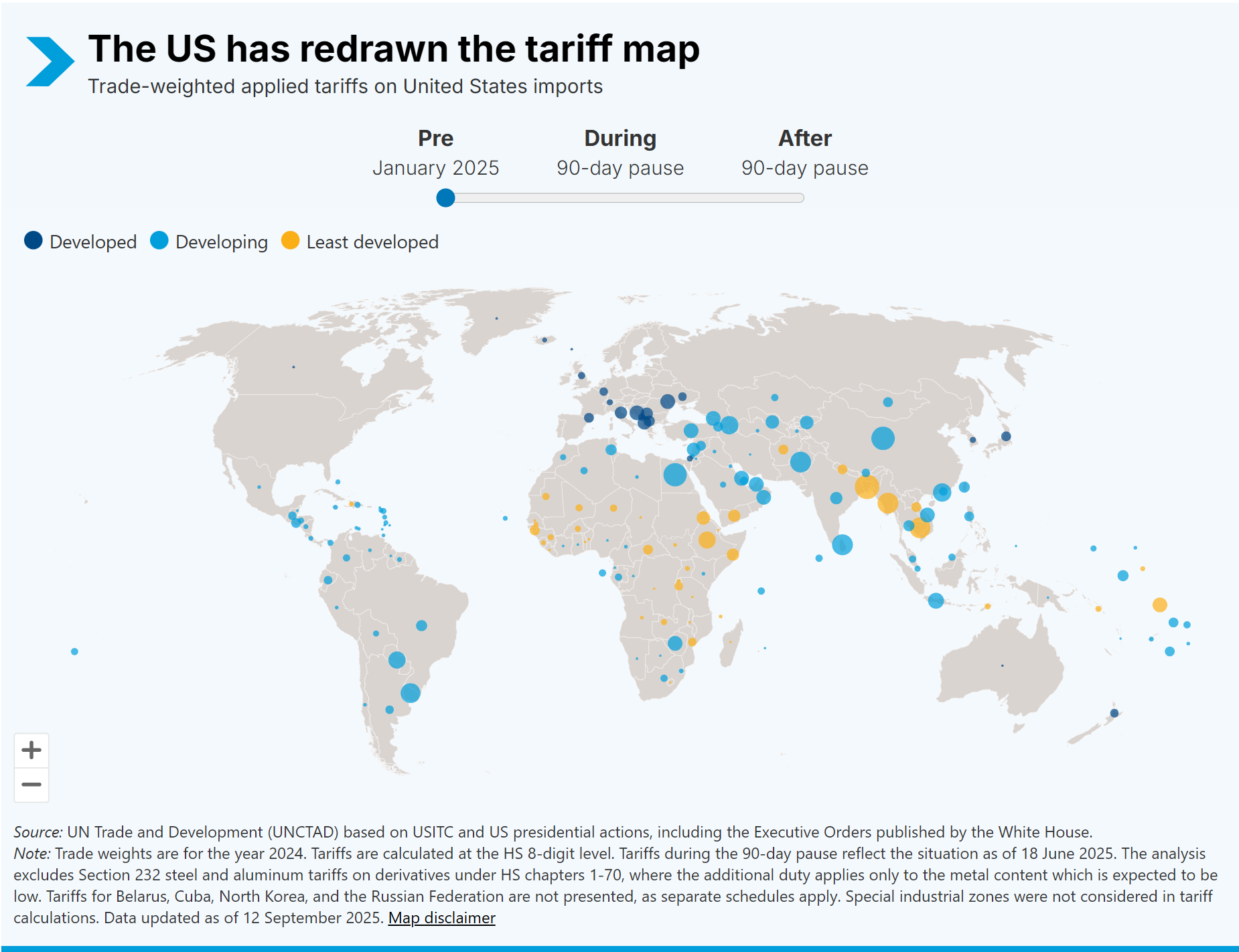

The United States has implemented new, differentiated tariffs on imports from almost all trading partners, with developing countries facing the steepest hikes.

The new measures signal a tectonic shift in US trade policy and a departure from rules that have underpinned the international trading system since the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), 30 years ago. They include higher and more differentiated tariffs by country, new duties imposed for non-trade-related reasons and an expansion of sectoral tariffs. While some major trading partners of the US have secured lower tariffs, poorer and more vulnerable countries have not. They risk being hit hardest.

The rise of tariffs

By introducing new country-specific tariffs, the US has departed from the WTO’s most-favoured-nation (MFN) principle, which requires equal treatment for trading partners. Instead, it’s applying different tariff rates to different countries to pursue a variety of goals, including reducing trade deficits or advancing non-trade-related policy objectives.

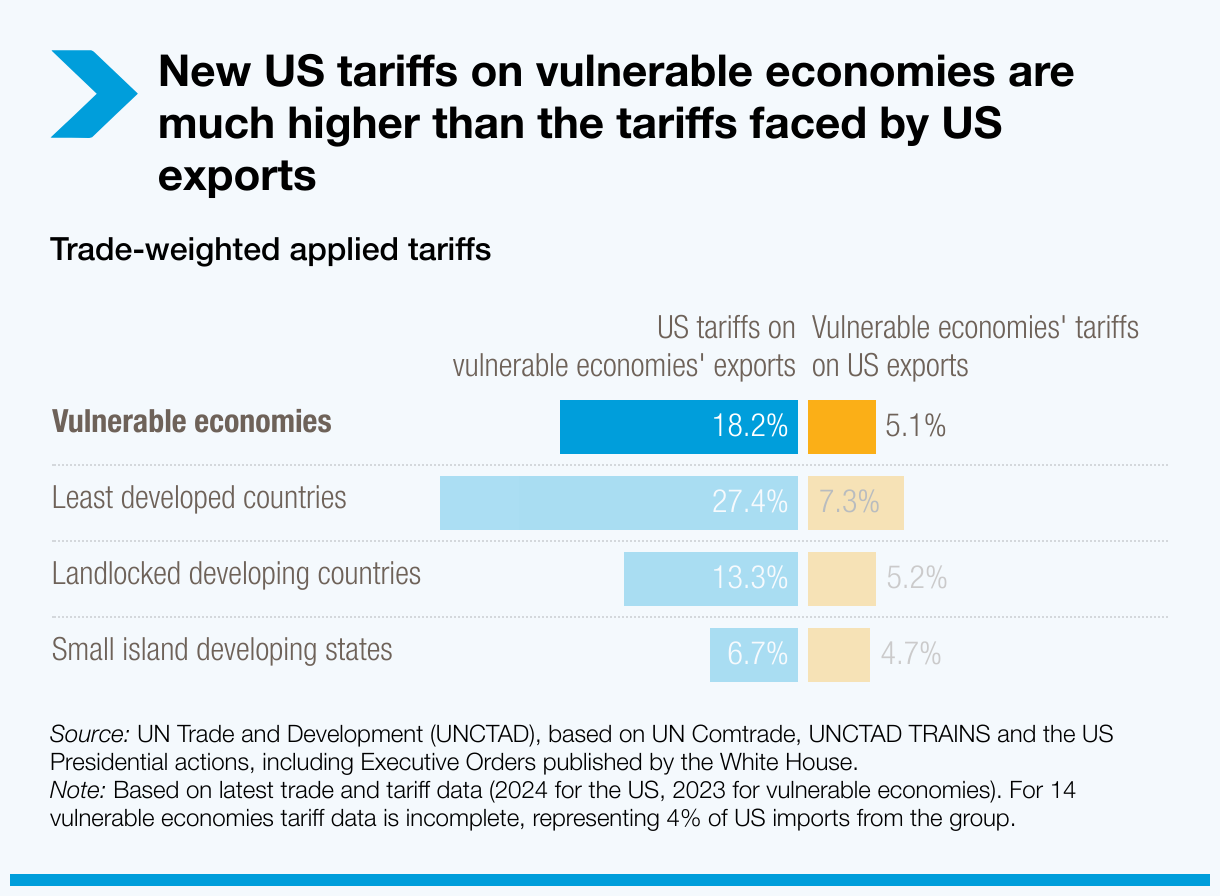

Many developing and least developed countries now face tariffs above 25%. This shift in tariff policy has resulted in US tariff rates increasing from an average of 2.8% before 2025 to over 20% by early September 2025. This sharp rise contrasts with the much lower tariffs that US exports face abroad, underscoring a growing imbalance in global trade relations.

For 16 developing countries – including five least developed countries – tariffs now surpass 25%. Initially set to take effect on 9 April, the country-specific US tariffs were delayed by 90 days and only came into force on 7 August 2025 after adjustments. This means the full weight of the new tariffs is only now hitting US imports.

The situation for African economies could worsen soon if the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) expires at the end of September 2025. Without an extension, country-specific tariffs would apply on top of MFN rates, instead of the current preferential rates under AGOA.

Some countries face extra duties for non-trade reasons

Beyond efforts to reduce trade deficits, tariffs are also being used to pursue non-trade-related policy goals. For example, the US has imposed an extra 40% in tariffs on most goods from Brazil in response to its domestic policies on social media and the prosecution of the former Brazilian president, and an additional 25% on India over oil imports from the Russian Federation.

Deep North American trade integration is under strain. Mexico and Canada are the US’ biggest trading partners and members of the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Yet additional tariffs of 25% and 35% (with some lower rates for energy-related goods and potash) have been introduced on goods from Mexico and Canada, respectively, that do not meet USMCA rules of origin. According to the US administration, these extra tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) are intended to help combat illegal border crossings and fentanyl trafficking.

Tariffs on China are relatively stable after a roller-coaster ride during the first months of 2025. On top of Section 301 tariffs (Title III of the Trade Act of 1974, "Relief from Unfair Trade Practices") and illicit drug-related tariffs, extra duties initially pushed the average US tariff above 100%, triggering retaliatory measures from China. Since mid-May 2025, average US tariffs on China have come down to 47% – initially for a period of 90 days. On 12 August, the period was extended for another 90 days to allow continued trade negotiations.

High sectoral tariffs are expanding

The US has also expanded its national security tariffs across various sectors. These sectoral tariffs are put in place under Section 232 of the Trade and Expansion Act of 1962, citing national security risks. They apply to all trading partners unless separate country-specific deals have been reached, but do not stack on top of the new US country-specific tariffs.

Tariffs on iron, steel, aluminum and their derivatives have risen sharply. In February, the US reinstated a 25% tariff on iron and steel and reinstated and raised the aluminum tariff from 10% to 25%. In June, both tariffs were doubled to 50%. Additionally, as of 18 August 2025, over 400 steel and aluminum derivatives now face a 50% tariff on their metal content, with the remainder subject to country-specific tariffs – and in some cases fentanyl-related tariffs.

New tariffs target automobiles and copper. A 25% tariff on automobiles imported into the US has been in effect since March, and on parts since May. On 1 August 2025, the US added an extra 50% tariff on copper and its derivatives.

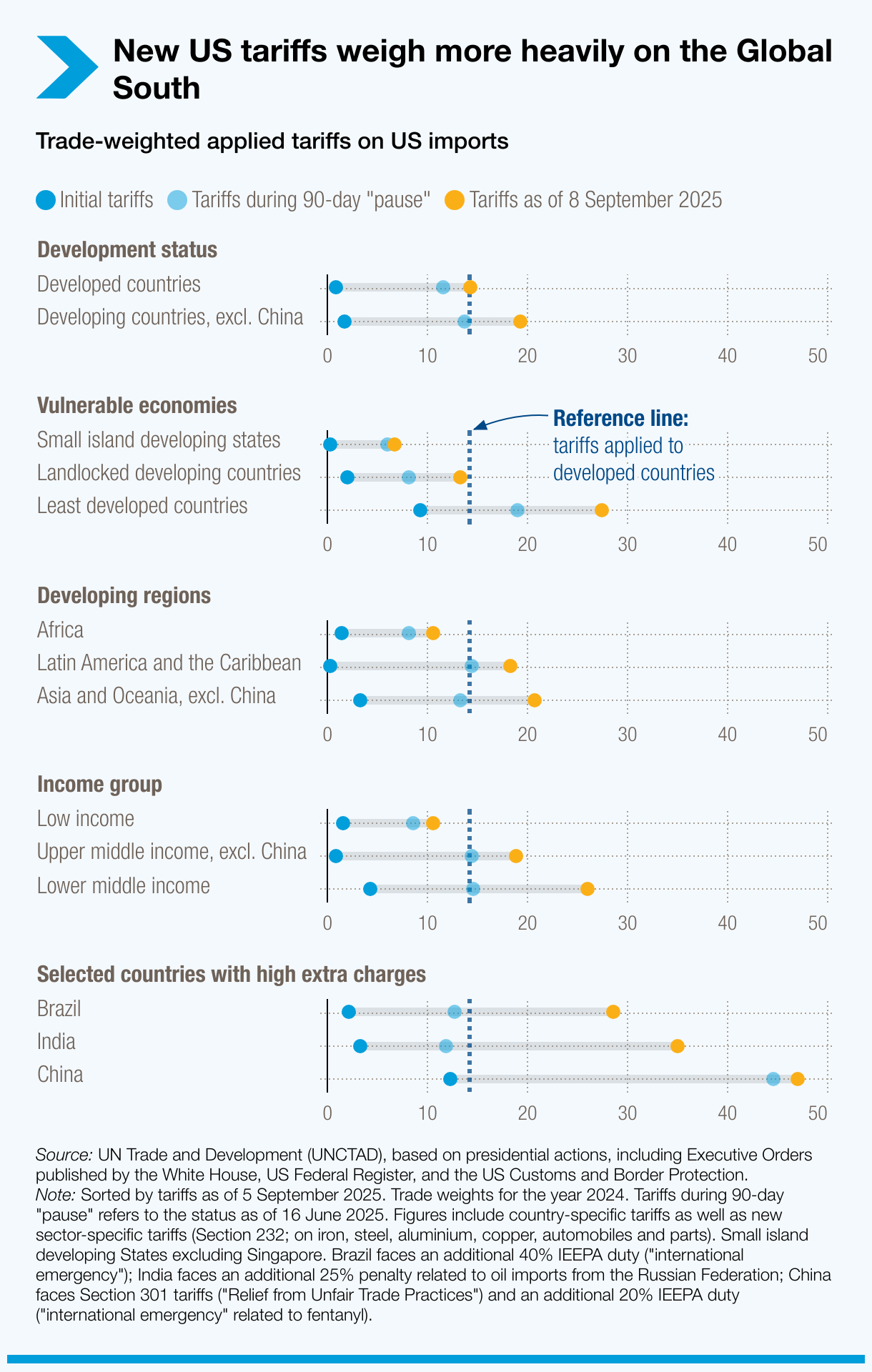

Poorer countries face some of the highest tariff hikes

Least developed countries (LDCs) and developing countries in Asia and Oceania are facing the sharpest tariff increases. For LDCs, the trade-weighted average tariff doubled to 19% during the “pause” and rose further to 27% in September. Trade-weighted averages reflect the effect of the new tariffs considering the mix of goods imported from each country in 2024. Tariffs on developing countries in Asia and Oceania increased from 3% to 13% during the ”pause” and climbed to 21% in September, even when excluding China.

In relative terms, however, Latin America and the Caribbean has experienced the greatest increase in tariffs. The US has 14 trade agreements with 20 countries, many of them in this region. These agreements have provided the region with preferential access to the US market, resulting in a trade-weighted average tariff of below 0.5%. This surged to 14% during the “pause” and reached 18% in September – a 60-fold increase. For small island developing states – mostly in the Caribbean – the trade-weighted average tariff rose 28-fold, from 0.2% to almost 7% in September.

It’s time for enhanced cooperation

Some of the largest or richest economies have secured lower tariffs, while vulnerable ones have not. Temporary, non-binding deals have benefited major economies. Based on UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) calculations, trade-weighted applied tariffs stand at 9.5% for the United Kingdom, 13.5% for the European Union and 19.4% for Japan, reflecting the effect of the new tariff rates and the mix of goods imported from each country in 2024. A retroactive application of tariffs for Japan, at rates comparable to those applied to the European Union, was announced by the White House on 4 September. Many of these deals involve pledges of increased investment in the US or reductions in tariffs on US exports.

Vulnerable economies with limited bargaining power pay a high price for new US tariffs. Among the 10 most affected countries are three LDCs: Myanmar (49%), Lao People's Democratic Republic (38%) and Bangladesh (35%). Dozens of vulnerable economies risk losing competitiveness in the US market, which could severely weaken their economies, as they tend to rely heavily on a narrow range of products and limited number of markets.

The current trajectory risks making trade less supportive of vulnerable economies. Sparing the most vulnerable economies from high tariff burdens should be a priority, but these countries should also be proactive. In addition to seeking exemptions through bilateral channels, vulnerable economies should prioritize diversifying export markets, investing in value-added production and building alliances within multilateral forums and regional trade blocks.

This is a difficult and uncertain time for international trade, but it could also mark the beginning of a new era of cooperation.