Summary

Many countries have adopted fiscal rules to foster fiscal discipline, but compliance has been mixed. Recent policy shifts and heightened policy uncertainty further intensify spending pressures and persistent debt challenges, underscoring the need for stronger fiscal guardrails. Results from a major update of IMF databases on fiscal rules and councils suggest that two-thirds of countries have revised their fiscal rules but deficits and debt continue to be well above countries’ rule limits. Robust correction mechanisms, with predefined timelines and measures, could better guide the return to rule limits and reduce sovereign spreads. In addition, supportive fiscal institutions, such as independent fiscal councils, reinforce compliance. Finally, revisions to fiscal rules to meet spending pressures should be carefully designed to preserve their integrity and transparency.

Subject:Debt sustainability,Expenditure,External debt,Fiscal councils,Fiscal governance,Fiscal policy,Fiscal rules

Keywords:Debt challenge,Debt sustainability,Debt-carrying capacity,Expenditures,Fiscal councils,Fiscal governance,Fiscal rules,Global,Heightened policy uncertainty,Looming spending pressure,Medium-term fiscal frameworks (MTFFs),Public debt,Public investment,Rule limit,SOVEREIGN RISK,Sovereign risks

Executive Summary

Over the past two decades, fiscal policy played a central role in responding to global shocks but at the cost of higher public debt. Large-scale stimuli during the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic increased public debt-to-GDP ratios. More recently, the rise in real interest rates associated with the normalization of monetary policy has reversed a decade of favorable financing conditions. As a result, fiscal space has shrunk in many countries, and vulnerabilities to future shocks have grown.

Countries have adopted fiscal rules as guardrails to foster fiscal discipline, but compliance has been mixed. Fiscal rules are long-lasting numerical limits on key budget aggregates, which are designed to contain excessive spending and the rise in debt. Empirical evidence suggests that fiscal rules could foster budgetary discipline (Azzimonti, Battaglini, and Coate 2016), signal a government’s commitment to sound fiscal management (Hatchondo and others 2022a, 2022b), mitigate procyclical spending (Reuter, Tkačevs, and Vilerts 2022; Eyraud, Gbohoui, and Medas 2023), and coalesce political debate (Cao, Dabla-Norris, and Di Gregorio 2024). On average, only about 60 percent of countries have complied with their rules. Even before the pandemic hit, noncompliance was already widespread, and the crisis widened deviations from fiscal rule limits significantly. These deviations often proved persistent, as many countries lack credible adjustment paths to return to rule limits. Hence, fiscal rules are often seen as lacking bites, particularly amid continued pressures to delay fiscal adjustment.

Looking ahead, pressures on public finances are set to intensify, underscoring the need to establish stronger fiscal guardrails, and to ensure compliance with them. Public debt remains elevated and is projected to rise further in many countries. Governments face mounting demands to scale up spending on defense, population aging, and sustainable development needs. Uncertainty surrounding fiscal policy has risen, and foreign aid to developing countries could decline given recent major shifts in trade policy and rising geoeconomic tensions. These further complicate the credibility and enforcement of fiscal rules. Against this backdrop, strengthening fiscal rule frameworks to rebuild buffers is more urgent than ever.

More than two-thirds of countries have revised their rules since the pandemic, but these revisions have often not translated into better compliance following the expiration of escape clauses. Many countries have struggled to unwind large deficits and high debt without robust corrective mechanisms to guide the return to fiscal rule limits. A key missing link is the lack of supportive fiscal institutions—such as independent oversight and unbiased macro-fiscal forecasts. This, in turn, has undermined credibility and made compliance with fiscal rules difficult.

Addressing gaps in fiscal rules and improving compliance requires a multi-pronged strategy. Drawing on the IMF’s Fiscal Rules and Councils databases, this Staff Discussion Note explores policies to improve compliance with fiscal rules. It highlights three key elements for improving compliance with fiscal rules in the face of growing policy uncertainty:

• A risk-based fiscal anchor—tailored to a country’s debt-carrying capacity—can help ensure that deficit or expenditure limits reflect underlying risks. This approach involves setting a quantified fiscal anchor that accounts for the risks a government faces and linking it to annual operational limits on expenditures or the budget balance. The goal is to gradually build fiscal buffers and avoid debt distress. To be effective, the fiscal anchor should be easy to communicate, aligned with institutional capacity, and complemented by a range of indicators to monitor debt risks. Countries facing high uncertainty on debt carrying capacity or undergoing debt restructuring may find it more practical to set expenditure or deficit ceilings to stabilize debt or to place debt firmly on a downward path rather than anchoring to a specific debt level.

• Robust correction mechanisms with predefined triggers, timelines, and policy responses to potential slippage can guide the return to rule limits and reduce sovereign spreads. Evidence shows that rules with strong correction mechanisms durably reduce spreads by 30−75 basis points.

• Supportive fiscal institutional frameworks—including realistic macro-fiscal forecasts, expenditure controls, strong links between fiscal rules and medium-term fiscal frameworks (MTFFs), and independent fiscal oversight—play an essential role in improving compliance and accountability. Stronger institutions and rules are associated with smaller fiscal surprises, lower sovereign spreads, and a more disciplined fiscal policy discourse.

Revisions to fiscal rules should be carefully designed when accommodating investment and other priority spending. Simulations suggest that a blanket exclusion of priority spending or prolonged delays in adjustment can erode the integrity of rules and jeopardize debt sustainability. As countries prioritize growth-enhancing spending and address spending efficiency gaps, revisions to fiscal rules should account for available fiscal space, risks surrounding the debt outlook, and the impact of spending. Low debt countries could ease rules within debt-stabilizing limits to scale up investment. In countries with constrained fiscal space, additional spending should be matched with higher revenues or expenditure reprioritization, otherwise loosening fiscal rules would put debt sustainability at risk.

I. Introduction

In a world of growing debt and policy uncertainty, fiscal challenges have come to the forefront. Over the past two decades, large fiscal support has cushioned major global shocks, including the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. This support has, however, contributed to high public debt levels worldwide, increasing vulnerabilities to future shocks and constraining fiscal space to address rising demand for quality public services.1 These pressures come at a time when interest rates are expected to rise as monetary policy normalizes, which would raise debt service burden and pose headwinds for public finances. As fiscal challenges intensify, countries are reconsidering how fiscal rules—defined as long-lasting numerical constraints on fiscal balance or expenditures—can be designed or revised to mitigate sovereign debt risks and guide fiscal policy in a more constrained environment.

Fiscal rules, adopted in more than 120 economies, can serve as vital guardrails for public finances, helping to reduce deficit bias and sovereign risks by committing to responsible fiscal policies. Over the last decade, countries have improved their risk-based fiscal rules by incorporating greater flexibility, which proved effective during the pandemic. However, compliance with these fiscal rules has been uneven, with an average compliance rate of about 60 percent across countries. At the same time, oversight from fiscal councils—technical nonpartisan entities entrusted as a public finance watchdog—has become more common, although their mandates and impacts often remain limited.

Several considerations warrant revisiting existing gaps in the design of fiscal rules and frameworks at this juncture. Previous IMF studies underscore the importance of a risk-based framework to establish a debt anchor and a corresponding fiscal path aimed at stabilizing or reducing debt while accounting for risks (Eyraud and others 2018; Arnold and others 2022; Caselli and others 2022, Fatas, Gootjes, and Mawejje 2025). However, new challenges have emerged. First, intensifying spending pressures complicate efforts to adhere to fiscal rules limits, including in low-income developing countries that face a potential decline in foreign aid. Second, despite recent revisions, fiscal rules often remain complex, have narrow coverage, and exclude certain government entities or expenditures. Many existing rules lack mechanisms to guide policy when noncompliance occurs. In some instances, fiscal rules fail to establish an appropriate anchor to build buffers and mitigate sovereign risks. While large economic costs of sovereign risk are noted in policy debates and academic papers (Bianchi, Ottonello, and Presno 2021; Arellano, Bai, and Bocola 2023), countries often lack a clear and consistent approach for reducing these risks. Finally, fiscal rules are often not supported by strong fiscal institutions and governance structures. Collectively, these limitations hinder governments’ ability to commit to fiscal discipline and comply with established fiscal rules.

Against this background, this note takes a fresh look at the design of fiscal rules and addresses the following questions:

1. How have fiscal rules changed after the pandemic? Do these changes address pre-existing and new challenges in terms of compliance and flexibility to address spending needs?

2. How can fiscal rules be better designed to improve compliance and reduce sovereign risks?

3. Should fiscal rules be revised in response to looming spending pressures? If so, how should they be revised?

This note finds that many countries have revised their fiscal rules since the pandemic; however, these revisions have not sufficiently addressed the issues of weak compliance. It highlights significant updates to the IMF Fiscal Rules and Councils databases, offering fresh insights into recent revisions and ongoing challenges. The enhanced data sets, covering 122 economies and 54 fiscal councils, provide broader country coverage and more detailed information on rules compliance and oversight (Alonso and others, 2025a). Since the pandemic, two-thirds of countries with fiscal rules have modified their frameworks, with varying success in achieving fiscal objectives. Significant deviations from established rules coupled with inadequate supportive fiscal institutions—such as independent oversight and macro-fiscal assessment —raise concerns about credibility and compliance.

The note presents new findings on enhancing the design of fiscal rules, emphasizing the importance of establishing a prudent fiscal anchor and effective correction mechanisms to ensure compliance with rule limits. It provides insights into calibrating a country’s sustainable debt limit, which is important for setting a prudent fiscal anchor. To evaluate the effectiveness of fiscal rules and fiscal councils, the note first analyzes the impact of a sound corrective mechanism on sovereign spreads. It then illustrates that stronger fiscal rules and well-functioning fiscal councils correlate with reduced fiscal projection bias and a less expansionary political rhetoric on fiscal policy. These novel results highlight that merely having fiscal rules and councils is insufficient for maintaining fiscal discipline; rather, it underscores the importance of well-designed rules and effective oversight to enhance fiscal responsibility.

Finally, this note presents a model-based framework to examine the impact of additional public investment on debt risks under various scenarios. Simulation results indicate that blanket exemptions for public investment or the prolonged use of escape clauses can compromise rule integrity and undermine debt sustainability. For low-debt countries, relaxing overly tight rules within debt-stabilizing limits can help facilitate financing for public investment. In contrast, high-debt countries with limited fiscal space must offset additional investment through higher revenues or spending cuts to keep debt under control. Well-calibrated rules, paired with strong investment management frameworks, can preserve credibility and foster compliance.

II. Recent Developments in Fiscal Rules Frameworks

The recent release of the IMF Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Council databases offers an updated overview of fiscal rule frameworks across countries.3 The update includes several significant enhancements, such as broader country coverage, detailed information on compliance and escape clauses, and new data on fiscal council communications. This data set is the first comprehensive compilation to include many small developing states. It also documents revisions to fiscal rules since the pandemic, providing insights into future fiscal rules designs as over two-thirds of countries have made revisions and established new fiscal councils.

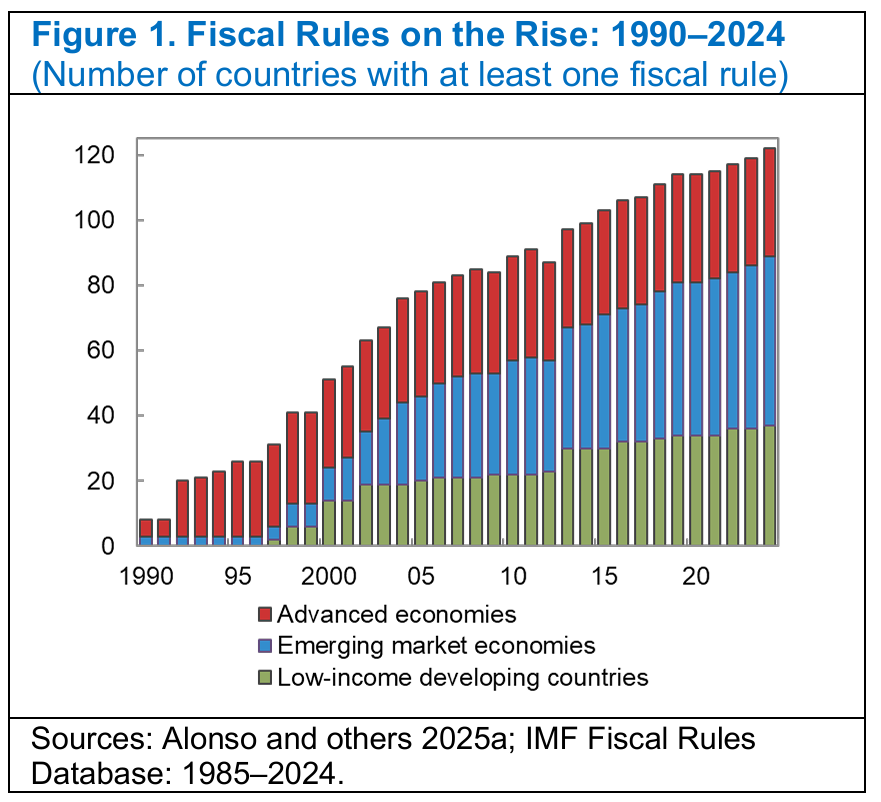

An increasing number of countries have adopted rules-based fiscal frameworks. As of the end of 2024, 122 economies have adopted numerical fiscal rules, representing a 6 percent increase since the pandemic. This growth is largely driven by emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) (Figure 1). Overall, more than two-thirds of countries have adopted multiple rules, typically combining a debt rule with annual budget limits on expenditure or budget balance. Many EMDEs have established fiscal rules to strengthen fiscal discipline or to avoid procyclical expenditures during significant fluctuations in commodities prices.

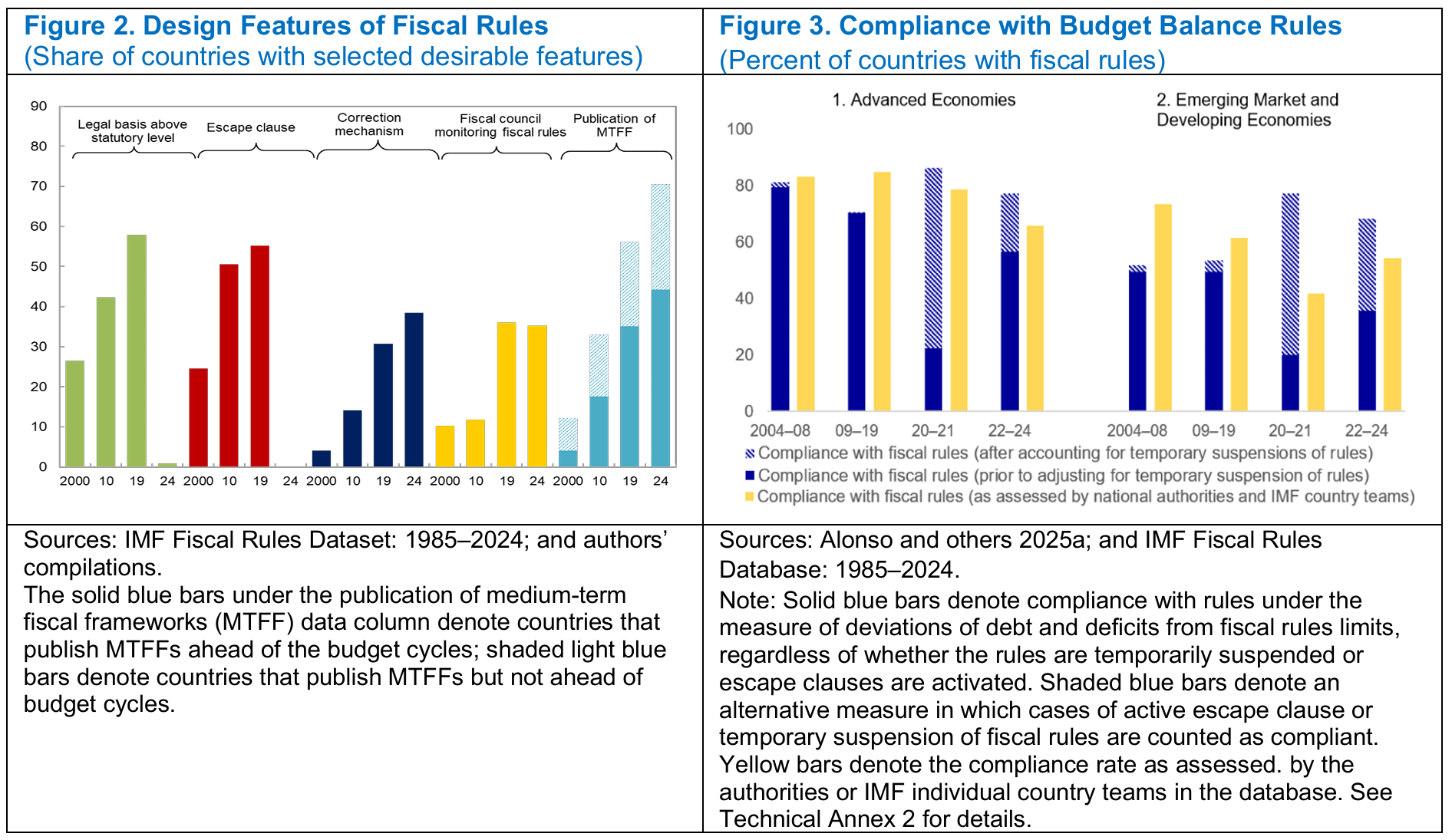

Although earlier fiscal rules were often too rigid, efforts to introduce greater flexibility have not translated into stronger compliance. Many countries have revised their fiscal frameworks to incorporate design features such as allowing automatic stabilizers to operate and embedding escape clauses for severe shocks (Figure 2). These changes aim to enhance the credibility of fiscal rules by allowing governments to accommodate adverse shocks without breaching their fiscal rule limits, addressing the reasons rigid rules were often disregarded. The increased flexibility in fiscal rules has proven effective during the pandemic, allowing governments to act swiftly to provide necessary support. However, despite this greater flexibility, compliance remains limited: fewer than two-thirds of countries adhere to their deficit rules on average (Figure 3), with lower share for emerging market and developing countries and debt rules. This finding suggests that flexibility in fiscal rules, while necessary, is insufficient on its own.

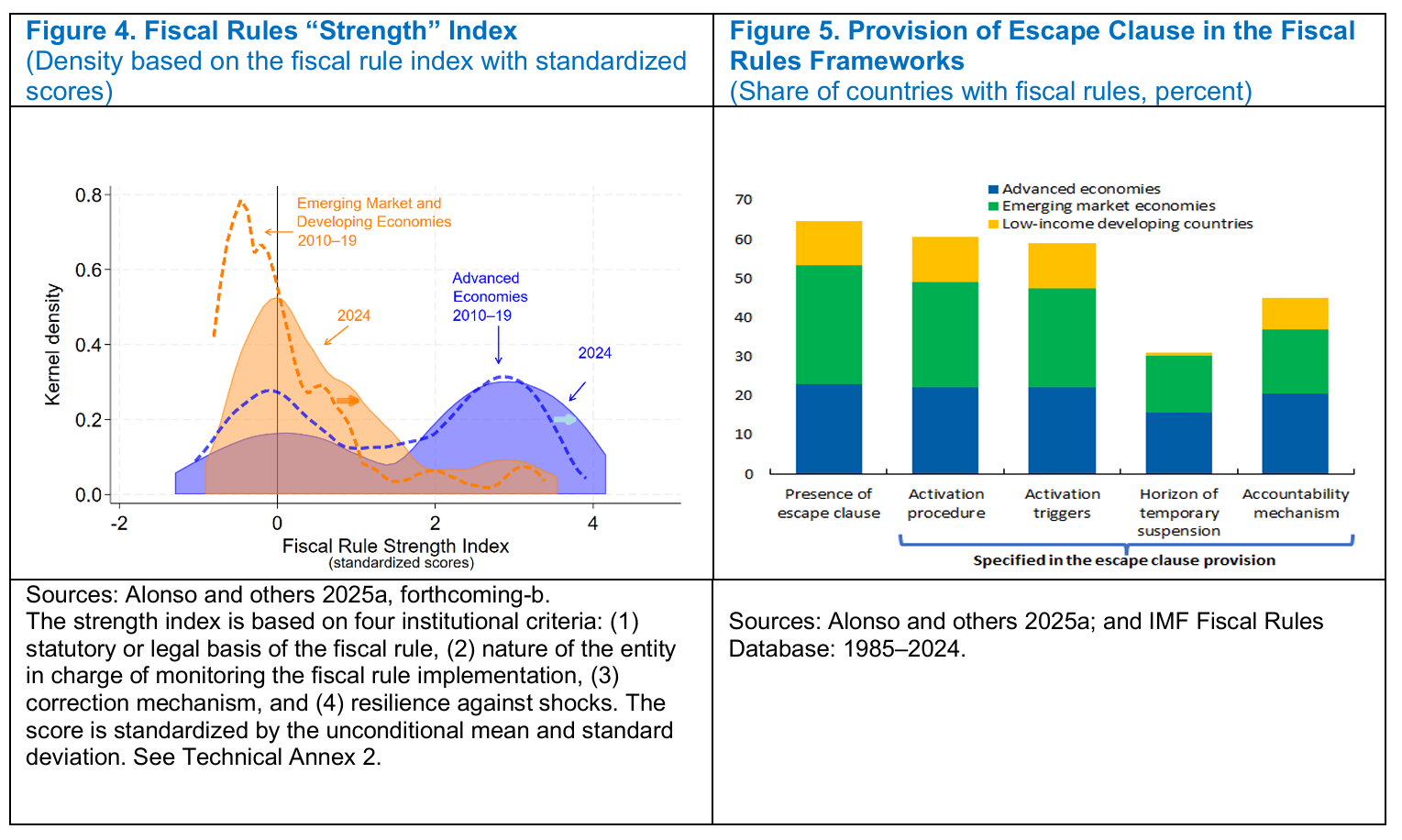

This note develops a “strength” index based on the attributes of fiscal rules to assess their effectiveness across countries and over time. Building on the measures developed in Davoodi and others 2022 and the European Commission’s Fiscal Rule Index (2023), the index is constructed using four institutional criteria: (1) the statutory or legal basis of the fiscal rule, (2) the monitoring of fiscal rules,(3) enforcement and correction mechanisms, and (4) flexibility and resilience to shocks (Technical Annex 2). Each indicator score is standardized between 0 and 1, with weights assigned on each rule.4 The scores are summed up to create a single index, which serves as a proxy for the strength of fiscal rules. The estimated “strength” index shows a high correlation (with a correlation coefficient of 0.8) with the European Commission’s index for EU countries.

Box 1. Assessing Compliance with Fiscal Rules The task of assessing compliance with fiscal rules across countries presents both conceptual and practical challenges. First, significant heterogeneity exists in the design and coverage of fiscal rules: some exclude local governments, off-budget entities, or investment spending; this complicates cross-country comparisons. Second, compliance assessments must account for the activation of escape clauses or temporary suspensions, which were widely used during the pandemic. Third, many rules are forward-looking, meaning that current deficits or debt levels may exceed targets applicable only in the future, complicating the interpretation of deviations. Finally, compliance is not always solely about numerical adherence; it often involves meeting procedural requirements, such as presenting fiscal plans or adhering to adjustment paths within the rules-based framework. To navigate these challenges, this Staff Discussion Note proposes a set of complementary indicators for assessing compliance with fiscal rules. The latest IMF Fiscal Rules Database includes direct assessments from national (or supranational) authorities and IMF country teams. In addition, this note introduces a simple metric based on observed deviations of fiscal outcomes from the relevant thresholds of fiscal rules, while accounting for instances where escape clauses are in effect or rules are suspended. Although not perfectly aligned with institutional assessments, these constructed indicators show a high degree of correlation with other studies (for example, Ardanaz, Ulloa-Suárez, and Valencia 2024; Larch, Malzubris, and Santacroce 2023) despite differences in methodology, definitions, and country coverage (Figure 3). Persistent deviations from fiscal rule limits arise from several reasons: severe macro-fiscal shocks, limitations in the design of fiscal rules, and political economy constraints. Severe shocks—such as the global financial crisis and the COVID19 pandemic—can lead to sharp increases in deficits and debt due to falling revenues and emergency spending. However, even in the absence of crises, many countries exhibit chronic deviations, often without immediate market penalties. The extended period of low interest rates before the pandemic reduced market pressure on countries running high deficits, weakening incentives for compliance (Dovis and Kirpalani 2020). Second, many fiscal rules suffer from design limitations: some are overly complex—especially supranational frameworks (Blanchard, Leandro, and Zettelmeyer 2021)—or contain multiple, internally inconsistent targets (Davoodi and others 2022a). Limited independent oversight further reduces the enforceability of fiscal rules. Finally, compliance often falters due to the lack of political will. A persistent deficit bias, combined with the rising popularity of expansionary fiscal narratives across the political spectrum, has undermined commitment to fiscal rules (Cao, Dabla-Norris, and Di Gregorio 2024). |

Although the overall strength of fiscal rules has improved, gaps in fiscal oversight and policy guidance regarding noncompliance remain. The strength of fiscal rules has improved across both advanced economies and EMDEs (Figure 4), reflecting more desirable design features, including escape clauses embedded in legislation. However, limited fiscal oversight persists, with less than half of countries having independent fiscal councils to monitor public finances by the end of 2024 (Figure 2). Moreover, majority of countries (with an even smaller share among EMDEs) do not have corrective mechanisms to manage noncompliance.

Countries also show limited accountability regarding escape clause provisions when suspending fiscal rules. Escape clauses provide flexibility to respond to severe shocks without undermining the edibility of fiscal rules. Although fiscal rules often prespecify the activation triggers for escape clauses, many do not specify the duration of these suspensions (Figure 5). This often results in extensions of 3 to 4 years even after severe shocks have subsided. The lack of reporting on strategies to return to compliance adds uncertainty to fiscal policy, particularly in the aftermath of severe shocks.

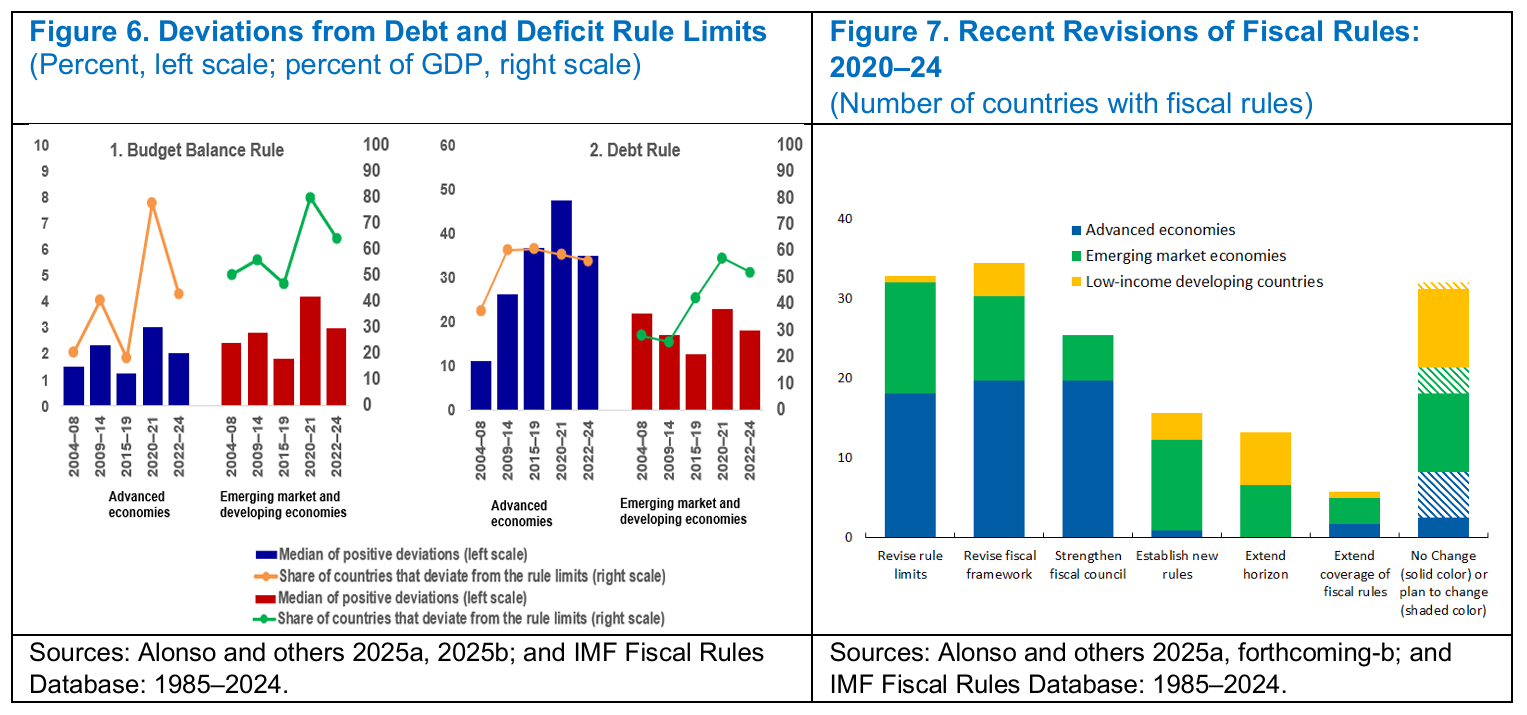

Fiscal deficits four years after the pandemic continue to exceed fiscal rule limits by a median of 2.0–2.5 percentage points of GDP for about 40 percent of advanced economies and 60 percent of EMDEs (Figure 6; Alonso and others, 2025b). In most countries, public debt has surpassed the ceilings in the debt rule by an average of 25 percentage points of GDP. Such large deviations from fiscal rule limits in many countries are driven by both severe shocks and limitations in the design of fiscal rules (Davoodi and others 2022a). During the severe shocks, the magnitudes and the share of countries that deviate from fiscal rule limits increased as expenditures or deficits tend to rise. But even in normal times, some countries have deficits and debt persistently exceeding their fiscal rule limits, partly because of multiple exclusions from the rules, limited fiscal oversight, or lack of fiscal adjustments to reduce debt and deficits. In recent years, fiscal adjustments have been limited, complicating the return to fiscal rule limits (Caselli and others 2022).

Governments have adopted various approaches to revise fiscal rule frameworks in an effort to improve compliance (Figure 7). Some countries have introduced new rules to complement existing fiscal rules to contain the debt buildup or demonstrate commitments. For example, Chile and Colombia have implemented a new debt rule, while the Dominican Republic has enacted its first fiscal responsibility law. Several countries have overhauled their fiscal frameworks; for example, the new EU fiscal rules allow for differentiated fiscal adjustments among member states based on their debt sustainability risks and reform efforts. A few countries have excluded entities or expenditure items from the rules (Armenia, Costa Rica). Others have extended the horizon to reach their fiscal anchors (countries in Eastern Caribbean Currency Union). A few countries have opted for greater flexibility by transitioning toward fiscal plans that emphasize multiyear commitments (India).

Click to read more