Summary

An Annual Borrowing Plan (ABP) guides the short-term execution of a debt management strategy, which typically spans 3–5 years. Emerging market and low-income countries have improved their ability to develop debt management strategy (DMS), they face ongoing implementation challenges. An ABP requires high-frequency data and detailed planning, considering factors like gross financing needs (GFN), seasonal revenue and expenditure patterns, and debt service obligations. Beyond supporting DMS implementation, an ABP offers several benefits: it helps to identify refinancing risks, assess financing feasibility, and detect funding gaps. It also contributes to market development, investor engagement, and transparency. Critically, an ABP links debt management with broader macroeconomic components—fiscal and monetary policy, cash flow forecasting, and market liquidity—making it a cornerstone of sound financial governance. Preparing an ABP involves several steps including: identifying the debt coverage, analyzing GFN, evaluating market conditions, selecting borrowing instruments, and aligning with DMS targets. Once finalized, an ABP should be approved by policymakers and published. While publication details vary by country, a high-level borrowing overview should accompany the national budget, followed by a more detailed version. An issuance calendar should also be published for government securities.

Subject:Asset and liability management,Budget planning and preparation,Debt management,Financial institutions,Government cash management,Government debt management,Government securities,Public financial management (PFM)

Keywords:Annual borrowing plan,Bonds,Borrowing plan,Budget planning and preparation,Caribbean,Debt financing strategy,Debt management,Debt management unit,Domestic debt,Financial markets,Government cash management,Government debt management,Government debt planning,Government securities,Granular ABP,IMF Library,Immunities ofThe World Bank,Issuance calendar,Loans,Market interest rates,Member country government,Plan tool,Public debt,Treasury bills and bonds,West Africa,Yield curve

Executice Summary

Emerging market and low-income countries have made good progress in formulating debt manage ment strategies in recent years, but implementation challenges remain. To support these efforts, in 2009, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) published guidelines to develop a medium-term debt management strategy (MTDS). The MTDS framework and its accompanying analytical tool (MTDS AT) supported the capacity-building efforts of the IMF and WB that began in earnest in the early 2000s. Countries’ progress on implementation has been mixed.

Implementing a debt management strategy (DMS) requires higher-frequency data and preparation of a clear plan of action through an annual borrowing plan (ABP). A DMS typically has a horizon of 3–5 years. Its implementation requires an action plan for the year ahead. The ABP requires more detailed information than the DMS. Furthermore, several factors determine the timing and size of borrowing within a given year, including the time profile of the gross financing need (GFN)—reflecting the seasonality of revenues and expenditures, and debt service.

Against this background, this note covers the process for preparing an ABP. The note is supported by an Excel-based tool (ABPT). The ABPT links directly with the MTDS AT, allowing for easier data sharing and ensuring data consistency between the two tools. The ABPT helps users to organize their domestic debt issuance operations, emphasizing the key role of Treasury bills (T-bills), which often serve both debt and cash management functions, alongside that of Treasury bonds (T-bonds). It also allows users to plan external borrowing.

Besides supporting the DMS, an ABP has several benefits. It helps the authorities to identify refinancing risk in advance, provide feedback on the feasibility of financing assumptions, and detect financing gaps. In addition, it contributes to market development, facilitates engagement with investors, and promotes transparency.

The ABP also plays a critical role in the formulation of the macroeconomic framework, in particular through its linkage with (1) debt management; (2) fiscal policy; (3) cash management operations and forecasts (inflows and outflows); (4) monetary policy, given the impact of government securities operations on market liquidity; and (5) market development.

The note describes key steps for preparing an ABP. These include identifying the debt coverage, obtaining the most recent GFN with the highest frequency, assessing macro and market conditions, identifying borrowing instruments, validating the ABP against DMS targets, and monitoring and reviewing the ABP.

Publication of the ABP is strongly recommended. The timing of publication and the level of detail will differ from country to country. However, a version that could present a high-level borrowing composition should accompany the budget, with a more refined version to follow. For government securities, an issuance calendar should be published.

The front office of the Debt Management Unit (DMU) should be in charge of preparing the ABP in close collaboration with the middle office. The middle office should also be involved, given its role in DMS development, risk management, and collaboration with other parts of government.

1.Introduction

A framework to develop a medium-term debt management strategy (MTDS) was published in 2009 jointly by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB) (WB-IMF 2019a). Drawing on the work in the aftermath of the sovereign debt crises in the late 1990s and early 2000s (in East Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere), and following the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative, in which official sectors provided debt relief to low- and lower-middle-income countries, the IMF and WB ramped up public debt management capacity-building support to their member countries. They published the MTDS framework and its accompanying analytical tool (MTDS AT) and provided a range of technical and capacity-building support, including guidance on developing a debt management strategy (DMS). The MTDS guidance for country authorities was updated in 2019 to incorporate more recent devel opments, including the wider variety of sovereign debt instruments. Since 2020, online training on the MTDS framework and MTDS AT has been available through the IMF’s massive open online course (https://www.imf. org/en/Capacity-Development/Training/ICDTC/Courses/MTDSX) and the WB’s interactive manual (https:// www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-toolkit/mtds) on using the MTDS AT.

A DMS typically has a time horizon of 3–5 years and is implemented through an annual borrowing plan (ABP). The ABP lays out the government’s borrowing plan for the year ahead, providing more detailed cash f low information than the DMS. Several factors determine the timing and size of borrowing within a given year, including the time profile of the gross financing need (GFN)—reflecting the seasonality of primary revenues and expenditures, and the debt-servicing schedule—market conditions, investor demand, and the need to adhere to sound primary market practices (for example, well-managed auctions and the develop ment of benchmark bonds).

Several emerging and low-income countries have made good progress in formulating a DMS, and many regularly publish their DMS.1 However, they have been less successful in their implementation through an ABP; feedback suggests that a key hurdle is the difficulty in translating the DMS into an actionable plan for the year ahead.

Against this background, the IMF and WB have prepared this technical note on designing an ABP and an accompanying Excel-based tool (ABPT). The ABPT links directly with the MTDS AT (allowing for easier data sharing and ensuring data consistency between the two tools) and uses a similar layout and terminology. It draws attention to the importance of coordination between debt management, cash management, and monetary policy operations through the impact of debt management activity on government cash balances and money market liquidity. The ABPT also supports users in structuring their domestic debt issuance activities, highlighting the central role of Treasury bills (T-bills), which frequently serve both debt and cash management functions, alongside Treasury bonds (T-bonds).

2. Annual Borrowing Plan

A. What Is an ABP?

An ABP is a single-year financing strategy that aims to meet the government’s GFN for the year ahead. It supports the debt manager’s primary objective to meet the government’s financing requirement, including debt service, on time and at the lowest possible cost, subject to a prudent degree of risk. Taking into consideration projections of revenues, expenditures, and debt service payments, the ABP outlines the financing plan to meet the GFN in the year ahead.

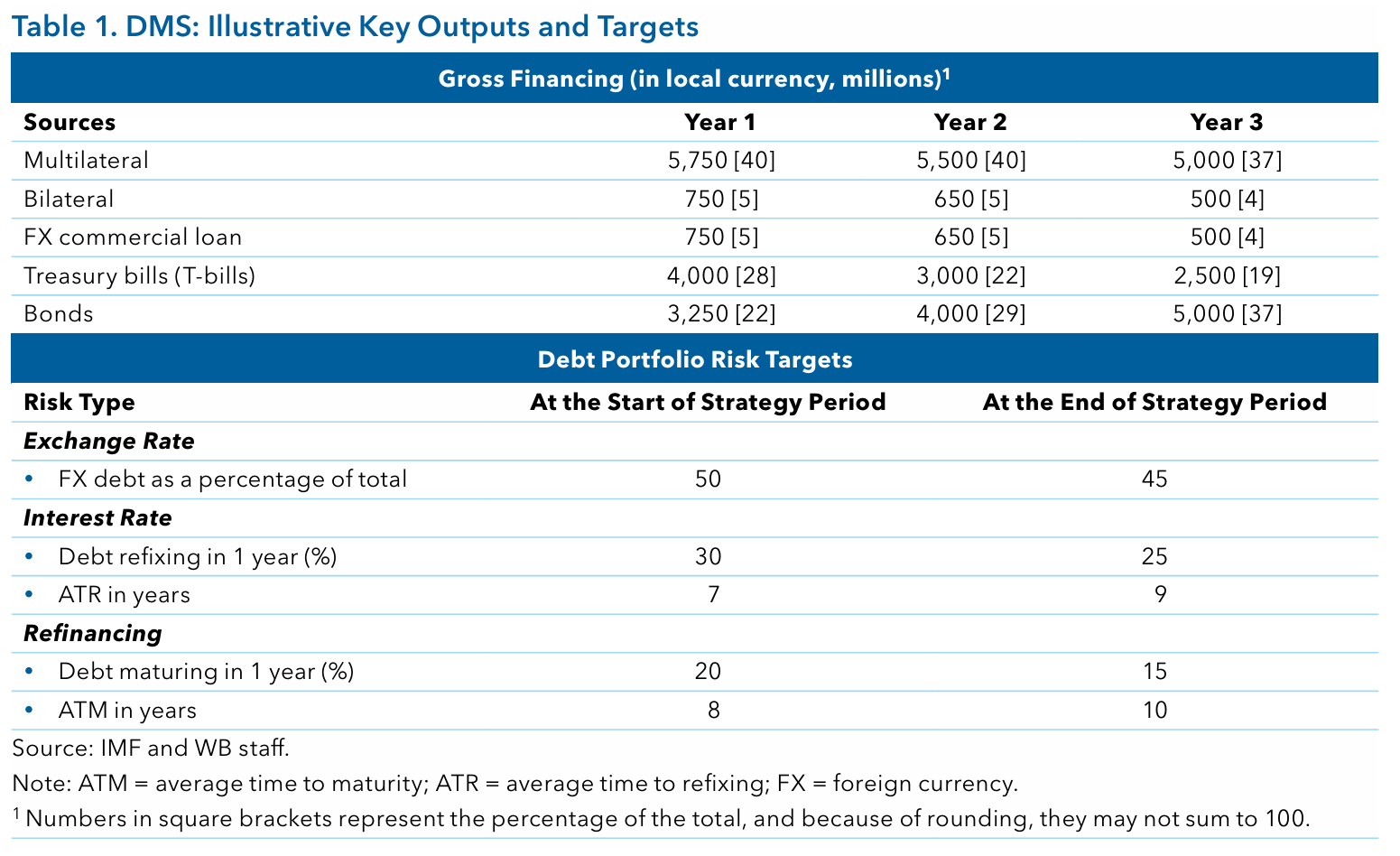

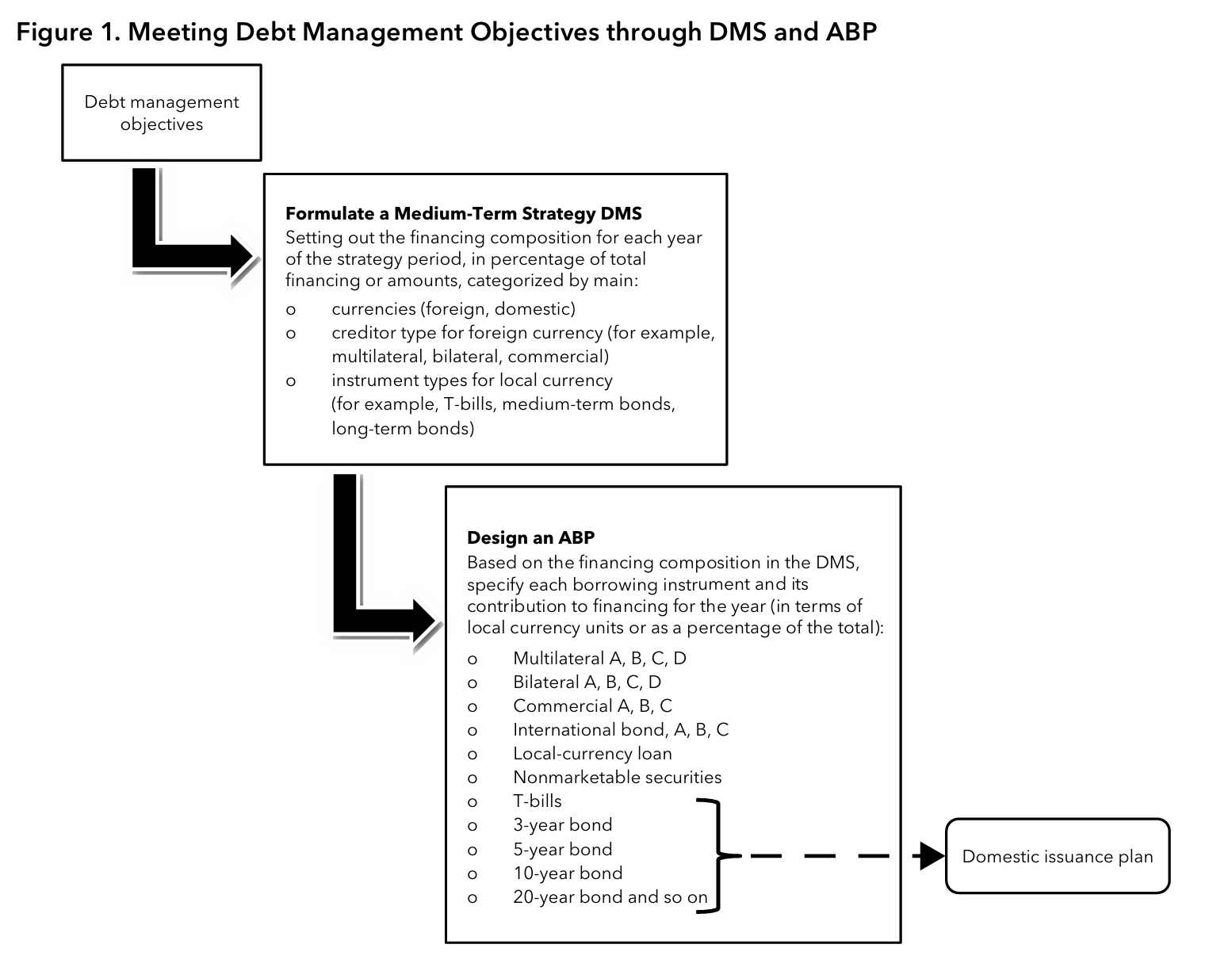

For countries that have a DMS, the ABP represents the implementation plan of the first-year financing strategy of the DMS. The DMS aims to comply with the government’s medium-term debt management objectives in accordance with its cost-risk preference (Figure 1). The DMS will often outline a financing plan for each year of the 3–5-year strategy period, consistent with the medium-term fiscal framework, setting out the financing sources by types of instruments and/or creditors, and currency—for example, foreign (FX) or domestic (DX).4 It also includes targets for debt portfolio risk indicators (whether expressed as point targets, ceilings, or a range) that the financing strategy aims to achieve, over the set time horizon (Table 1).

The ABP covers the first-year financing strategy of the DMS in greater detail, the outcome of which should result in a debt composition that transitions the sovereign’s debt portfolio toward the DMS targets.

Source: IMF and WB staff.

Note: ABP = annual borrowing plan; DMS = debt management strategy.

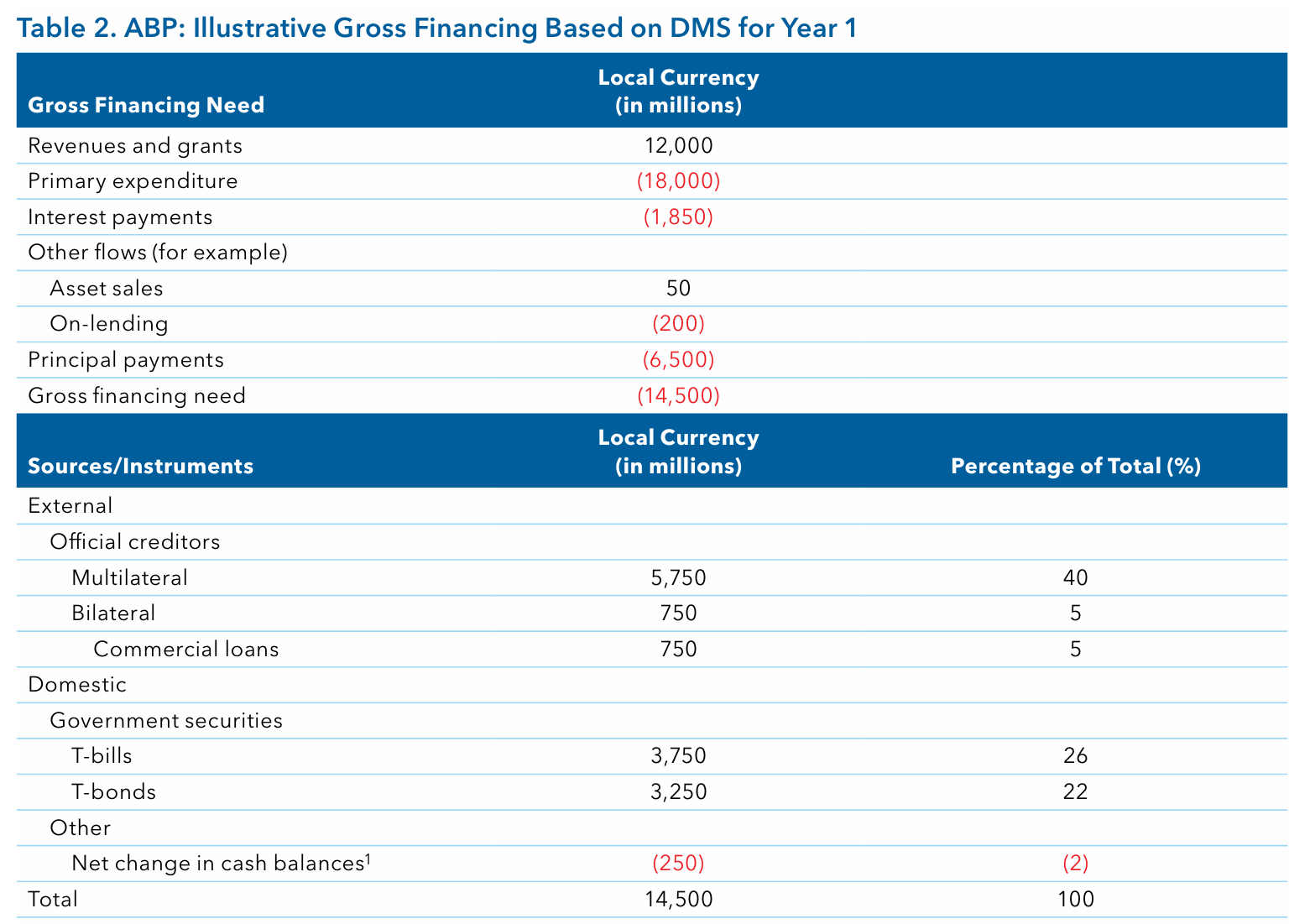

The ABP includes details on the specific instruments, such as loans and securities, to be used and/or the relevant creditors in the forthcoming year (Table 2). For FX borrowing, planned disbursements from each official creditor, loans from the private sector (including commercial loans), and any planned international bond issuance should be included.5 For DX borrowing, the financing plan should distinguish between loans (including from the monetary authorities if applicable), nonmarketable, and marketable securities, with an indication of the split between tenors (Figure 1).6 As in the DMS, the ABP can express the financing composi tion in either nominal amounts by currency or as percentages of the total.

Source: IMF and WB staff.

1 A negative change signifies cash drawdown, which contributes to financing. Thus, domestic sources are projected to contribute 50 percent of total financing, with 2 percent sourced from cash drawdown.

B. Benefits of an ABP

The process of preparing the ABP helps policymakers to focus on the detailed financing options for the year ahead. Even if the period between completing the DMS and preparing the ABP is short, new information on borrowing conditions may have to be reflected.7 In shifting the focus from the 3–5-year DMS to the year immediately ahead, debt managers have to consider expected market conditions and other shorter-term factors whose impact will be felt in the time horizon of the ABP.

An iterative information-sharing process during ABP design and budget formulation ensures their consis tency and strengthens coordination with policy implementation. In designing the ABP, debt managers should incorporate the fiscal borrowing needs reflected in the government’s annual budget. In turn, in developing the annual budget, the fiscal authorities should reflect not only debt service projections provided by the debt manager but also their advice on the sums that can be realistically borrowed. Without this interaction, debt manager may be required to borrow in amounts that may not be feasible or that will have an undesir able impact on debt composition (for example, shortening of average maturities). A consequence could be to destabilize the domestic debt market, leading to higher and more volatile yields. The ABP should also inform the budget process, including providing inputs for monitoring gross or net borrowing limits.

An ABP allows the authorities to:

Manage refinancing risk. The design process of the ABP facilitates risk management, in particular for in-year refinancing risk by enabling the consideration of a range of mitigating approaches. This includes the buildup or use of cash buffers or liability management operations, such as buybacks or exchanges in which a portion of maturing debt is redeemed for cash or exchanged for other securities ahead of its maturity.

Provide feedback on the feasibility of borrowing the amounts needed to cover the GFN. The ABP enables debt managers to inform the fiscal authorities whether the GFN resulting from their proposed budget can be met through borrowing, thus allowing revisions of the budget if necessary.

Detect and address potential in-year financing gaps. The ABP facilitates informed decisions on how f inancing needs will best be met, taking into account borrowing conditions. Developing and imple menting an ABP is a dynamic exercise that depends on new information on borrowing conditions. As such, the ABP helps detect and address well in advance potential in-year financing gaps and constraints that may affect its successful implementation.

Engage effectively with investors and stakeholders. The communication of the ABP and the issuance calendar facilitates the relationship with investors and enhances transparency. Market consultations on the issuance calendar provide opportunities to engage effectively with investors and stake holders. The publication of the issuance calendar contributes to more transparent and predictable debt issuance operations, which facilitates investor planning. Active communication about the ABP reduces information asymmetry between issuers and investors and may contribute to reducing the risk premium demanded by investors.

Plan a debt issuance profile that supports market development objectives. The ABP preparation process helps to develop the domestic debt market by enabling a careful assessment of the pace at which a benchmark yield curve can be built and which benchmark maturities can be launched.

Monitor progress against the DMS. An ABP designed in accordance with a DMS facilitates the moni toring of progress against the DMS by tracking cost-risk indicators.

Increase the transparency of debt management operations and provide discipline to borrowing activities. Publishing the ABP and issuance calendars is a sound debt management practice; indeed, transparency gives credence to the ABP. Publication of the ABP also strengthens the government’s commitment to predictable issuance activities and can contribute to reducing uncertainty related to issuance activities. In contrast, opportunistic issuance or issuance on a discretionary basis in terms of timing, maturity, and size will constrain investors’ ability to anticipate and plan for issuance activities and can increase the risk premium over time.

Click to read more