Abstract

Platforms, retailers, and other firms often offer their own products alongside products sold by competitors. We study the effects of this practice by combining a field experiment that hides brands owned by Amazon (i.e., private labels) from shoppers on Amazon.com with model-based counterfactuals and welfare analysis. In the absence of private labels, consumers substitute toward products that are similar along most observable dimensions. Removing Amazon brands does not change consumers’ search effort or their propensity to shop at other retail websites. Despite the ample availability of observably similar alternatives, our welfare estimates imply that, for the categories we study, removing Amazon brands would reduce consumer surplus by 5.4 percent in the short run, with approximately 10 percent of the impact due to equilibrium price increases by other sellers. The effects are heterogeneous, with consumer surplus reductions exceeding 10 percent in some categories, while other categories realize much smaller decreases when Amazon brands are removed. Demoting private labels in search results to counteract potential self preferencing does not lead to gains in consumer surplus. This outcome arises because a subset of consumers derive greater utility from private labels and benefit from their high placement in search results.

1 Introduction

Digital platforms such as Amazon and Google are so large and influential that many of their actions are under regulatory scrutiny. In Europe, regulators have recently passed the Digital Markets Act1 and the Digital Services Act2 to constrain and monitor the behavior of large plat forms. In the US, the Department of Justice (DOJ) is involved in legal proceedings against Google3 and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) against Amazon,4 both of which accuse the platforms of abuse of their respective dominant positions.

One issue of regulatory concern is the practice by major technology platforms of vertically integrating and featuring their own products alongside those of third parties. This practice is common among the large firms designated as “gatekeepers” by the Digital Markets Act. For example, Google owns Google Maps and Google Shopping, which directly compete with third party maps and e-commerce alternatives. Similarly, Amazon sells private-label products—under brands such as Amazon Basics, Solimo, and Mama Bear—on its retail website alongside com peting products offered by independent manufacturers and brands. This practice has raised concerns of reduced competition and harm to consumers, especially if the gatekeeper treats its own products more favorably, i.e., engages in self-preferencing.

We study the effects of Amazon-owned brands, or private labels, on consumer decisions and welfare. To answer this question, we develop a browser extension that can manipulate and track browsing behavior and recruit participants to install it. We use the extension to introduce random variation in the set of products available to consumers. For our main treatment, we pre vent consumers from seeing Amazon brands when they browse Amazon’s website. This allows us to measure the (short-run) effects on search behavior and product choices in the absence of Amazon’s private labels.

We focus on four demand-side channels by which the presence of private label products can affect consumer welfare. First, their presence increases the number of options that con sumers can choose from—the variety effect. Second, consumers may adjust their effort when they search for products on Amazon. Third, private labels may influence whether consumers shop on Amazon instead of Walmart.com, for example. Fourth, competitive pressure can affect equilibrium prices of other products.

We use our experimental variation to provide reduced-form evidence on the extent of the f irst three mechanisms. We find that when Amazon brands are not available, consumers substi tute to broadly similar products, except that those substitutes have fewer reviews. We find no evidence of changes to search behavior on Amazon, nor evidence that consumers spend more time on other online retail sites. To assess the fourth mechanism, we estimate a structural model of demand and use the model to simulate counterfactual equilibrium prices in the absence of Amazon brands. The model allows us to quantify changes in consumer welfare. The presence of Amazon brands increases welfare, but mainly through the effects of the brands on consumer choices rather than inducing competitors to lower prices.

For this research, we developed a browser extension called Webmunk, recruited US residents to install it, and compensated them for their participation.5 The extension randomly allocates study participants into three groups: a control group, whose behavior on Amazon.com is tracked for the period of the study; a Hide Amazon group, for whom the extension removes Amazon brands from search results and other pages on Amazon.com; and a Hide Random group, for whom the extension removes a random set of products.

Upon enrollment, we ask participants to complete a set of incentivized shopping tasks and then track their organic browsing behavior on Amazon for the following 8 weeks. In the incen tivized tasks, participants are asked to shop for products from pre-defined categories to add to an Amazonwishlist especially created for our study. We pre-selected 23 product categories (e.g., allergy medications, paper towels, socks, batteries) from a set of six meta-categories—health, paper products, household items, apparel, electronics, and personal care. The first five meta categories are characterized by a high share of Amazon branded options. The sixth, personal care, did not have Amazon brands at the time of our study, and we selected it as a placebo.

The randomization allows us to compare the characteristics of the chosen products across the three treatment groups.6 In the absence of Amazon brands, consumers choose products with similar price, delivery characteristics, average star rating, and Prime eligibility, showing no statistically significant differences from those selected by the control group. Though the average star rating is similar, the number of accumulated reviews of the chosen product is much lower when Amazon brands are hidden compared to when Amazon brands are available. The Hide Random group allows us to confirm that these differences are not simply due to a decrease in product variety, but directly linked to the characteristics of Amazon branded products.

Notably, this substitution toward similar products does not appear to require additional ef fort from consumers. The number of searches performed and the number of products viewed remain comparable across treatment groups, suggesting that consumers are able to find alter native products without engaging in a more extensive search process. Furthermore, traffic to other retail websites outside of Amazon does not increase when Amazon brands are hidden, in dicating that consumers remain within the platform and simply shift to comparable alternatives rather than seeking options elsewhere.

These substitution patterns are consistent with stated consumer preferences in our surveys. Indeed, consumers say they care more about prices, delivery, and quality (as proxied by online ratings) than brand or seller reputation. When asked to rate the chosen products they received from the incentivized shopping task, consumers scored them similarly, regardless of whether they had access to private labels. On average, participants indicated that they valued Amazon private labels $1.75 less than comparable non-Amazon products priced at $25. When the ref erence product is priced at $10, Amazon brands are valued $0.18 less. The average difference masks substantial heterogeneity across respondents. Stated preferences indicate that the rela tive preference for Amazon brands compared to other products can be offset by other variables such as average ratings and delivery speed.

To further understand consumer preferences for Amazon private labels and to measure their effects on welfare, we estimate a structural model of demand and supply. We use a discrete choice demand model with heterogeneous preferences across individuals for features like price and Amazon brands. Using individual product selections, we estimate the model via maximum likelihood, while calibrating the mean own-price elasticity to a value of −5 to match reported data on margins for Amazon sellers. Our demand estimates imply that Amazon brands are val ued less than other major brands but slightly more than other non-Amazon products. Further, there is meaningful variation in preferences for Amazon products across consumers. Our es timates imply mean marginal costs of roughly $15 and own-price elasticities that range from-8.71 to-2.14 at the 10th and 90th percentiles.

Weuse the structural model to measure the effects of removing Amazon products from con sumers’ consideration sets. We remove Amazon brands, shift the remaining products upward in search rankings, and re-compute equilibrium prices. For the product categories in our sam ple where Amazon brands are present, we estimate that removing Amazon products reduces consumer surplus by 5.4 percent—$0.17 per search—due to reductions in product variety and pricing pressure on competing products. Just over 10 percent of the loss in consumer surplus is due to higher equilibrium prices for the remaining products.

We find sizable heterogeneity in the effect on consumer surplus across categories. In princi ple, if Amazon excessively prioritizes its own private-label products, their removal can lead to the promotion of alternatives that consumers perceive as superior. As these products move up in the search rankings and are chosen more frequently, the resulting quality improvement can offset—or even outweigh—the effects of higher prices, ultimately increasing consumer surplus. Despite this theoretical possibility, we find that removing Amazon products reduces consumer surplus across all categories. The effect is largest for batteries, acid reducers, monitor cables, and trash bags, whereas it is smallest for laundry detergents, umbrellas, and moisturizers.

Motivated by recent regulatory actions prohibiting self-preferencing, we also examine a counterfactual scenario in which Amazon’s private-label products are demoted in search rank ings to positions consistent with their observable characteristics or positions consistent with their average utility across consumers. Under both protocols, we find that the demotion of prod ucts slightly reduces consumer surplus. Contrary to what regulators might expect, the changes in consumer welfare from these corrections to self-preferencing are not positive. This is be cause a substantial segment of consumers derive greater utility from Amazon’s private labels and benefit from their prominence in search results.

Our study is subject to limitations. Our design ensures that the participants have been active Amazonshoppers. Further, we require that participants use a computer browser when they shop online (rather than a smartphone or a tablet). Because of these margins of selection, as well as the fact that participants elect to join an online study, our results may not completely generalize to the full population of online shoppers. Another limitation is that our study was conducted over a limited time frame: an incentivized shopping task followed by a 8-week observational period. Consumer behavior along various margins, such as search and cross-platform behavior, may take longer than 8 weeks to adjust to the removal of Amazon brands. Thus, the results from our experimental variation are limited to short-run effects. Similarly, our counterfactual simulations only measure price adjustments on the supply side, and depend in part on correctly specifying demand and supply. We abstract away from longer-run effects such as changes to non-price characteristics and the entry of new products.

Related literature. Recent regulatory scrutiny over the market power of digital platforms has given rise to a new literature on vertical integration and biased intermediation (Hagiu, Teh and Wright, 2022; De Corniere and Taylor, 2019; Teng, 2022), specifically on Amazon (Lee and Musolff, 2022; Gutierrez, 2022; Lam, 2022; Crawford et al., 2022; Chen and Tsai, 2021; Raval, 2022; Reimers and Waldfogel, 2023; Waldfogel, 2024). Relative to the above papers, our work has several key advantages. First, our data contain searches and product selections from a variety of real consumers. Second, our field experiment allows us to draw causal links between ranking and consumer choices, and between the availability of Amazon brands and substitution patterns. Third, we link the shopping behavior on Amazon to surveys, order histories, and visits to non-Amazon retailers, shedding light on the generalizability of our results based on incentivized shopping tasks (Morozov and Tuchman, 2024) for more organic search and shopping behavior (Ursu, 2018; Santos, Hortac¸su and Wildenbeest, 2012; Dinerstein et al., 2018).

Our approach to collecting data and studying consumer behavior contributes to recent and growing research that uses software to track consumers and run online experiments. Allcott, Gentzkow and Song (2022) study the addiction properties of social media use. Aridor (2022) observes participants’ substitution patterns when he experimentally shuts off access to Insta gram or Youtube. Levy (2021) differentially exposes study participants to news outlets on so cial media to study its effects on political polarization. Beknazar-Yuzbashev et al. (2022) study the effects of removing toxic content on social media consumption, highlighting the trade-off between consumption and content toxicity. More recently, Allcott et al. (2024) use a similar approach to identify the reasons behind Google’s dominant position in online search.

Our paper relates to a large literature on private labels, mostly focused on offline retail. Private labels are standard practice offline, accounting for almost 20% of products sold (Dub´ e, 2022). In comparison, we find that Amazon brands are only 2.5% of products sold in the Ama zon order histories of our study participants, who are particularly active Amazon shoppers. An older literature has found positive benefits from the introduction of private labels in physical retail, by offering consumers cheaper alternatives of similar quality (Newmark, 1988), with out negatively affecting competition, and instead improving it (Adelman, 1949). Research has shown that there are a variety of reasons why retailers may offer private labels (Dhar and Hoch, 1997), from imitating national brands at lower prices (Scott Morton and Zettelmeyer, 2004), especially the most successful brands (ter Braak and Deleersnyder, 2018; Zhu and Liu, 2018), to ensuring quality (Hoch and Banerji, 1993) and offering a variety of premium and value op tions (Ter Braak, Dekimpe and Geyskens, 2013). Relatedly, Ailawadi, Pauwels and Steenkamp (2008) find that private labels increase store loyalty.

Previous work has also demonstrated how traditional retailers often preferentially treat their private labels (Kumar et al., 2007), by physically placing them prominently (Kotler and Keller, 2016), sometimes side by side with national brands, using similar packaging, discounts, free samples, and comparative messaging (Bronnenberg et al., 2015; Bronnenberg, Dub´ e and Sanders, 2020; Bronnenberg, Dub´ e and Joo, 2022). Despite the prevalence of these practices offline, regulators have taken a different approach towards Amazon and its private labels given the dominant position that Amazon and other similarly large platforms have in their respective markets (Dub´ e, 2022). In our research, we take these concerns over market power seriously and empirically assess whether and to what extent Amazon’s private labels distort consumer choice or harm competition. By leveraging randomized experimental variation, we provide direct evi dence on the actual impact of private labels on consumer behavior and market outcomes. A key feature of our online setting is that we can directly measure and manipulate product placement, which we find to be meaningful for consumer choice.

Therest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes our data collection method ology and presents summary statistics about our study population. In Section 3, we present reduced-form evidence on demand effects, including substitution between Amazon brands and non-Amazon brands, search effort, and cross-platform effects. The section also discusses our reduced form results in light of perceptions of Amazon brands that consumers report through survey responses. Section 4 presents our structural demand model and counterfactual estimates of impacts to equilibrium prices and welfare. Section 5 concludes.

2 DataCollection

Our study uses a custom browser extension called Webmunk. Webmunk is an extension similar to an ad blocker and can be installed on the Chrome browser of any computer. The extension has three crucial functionalities. First, it prompts participants to perform specific tasks. Second, it tracks participants’ browsing behaviors on pre-determined websites. Third, it allows us to manipulate participants’ browsing experience to create different treatment conditions across users and estimate treatment effects of interest. We discuss each of the three functionalities as part of the study design, and then present our sample of study participants.7

2.1 Study Design

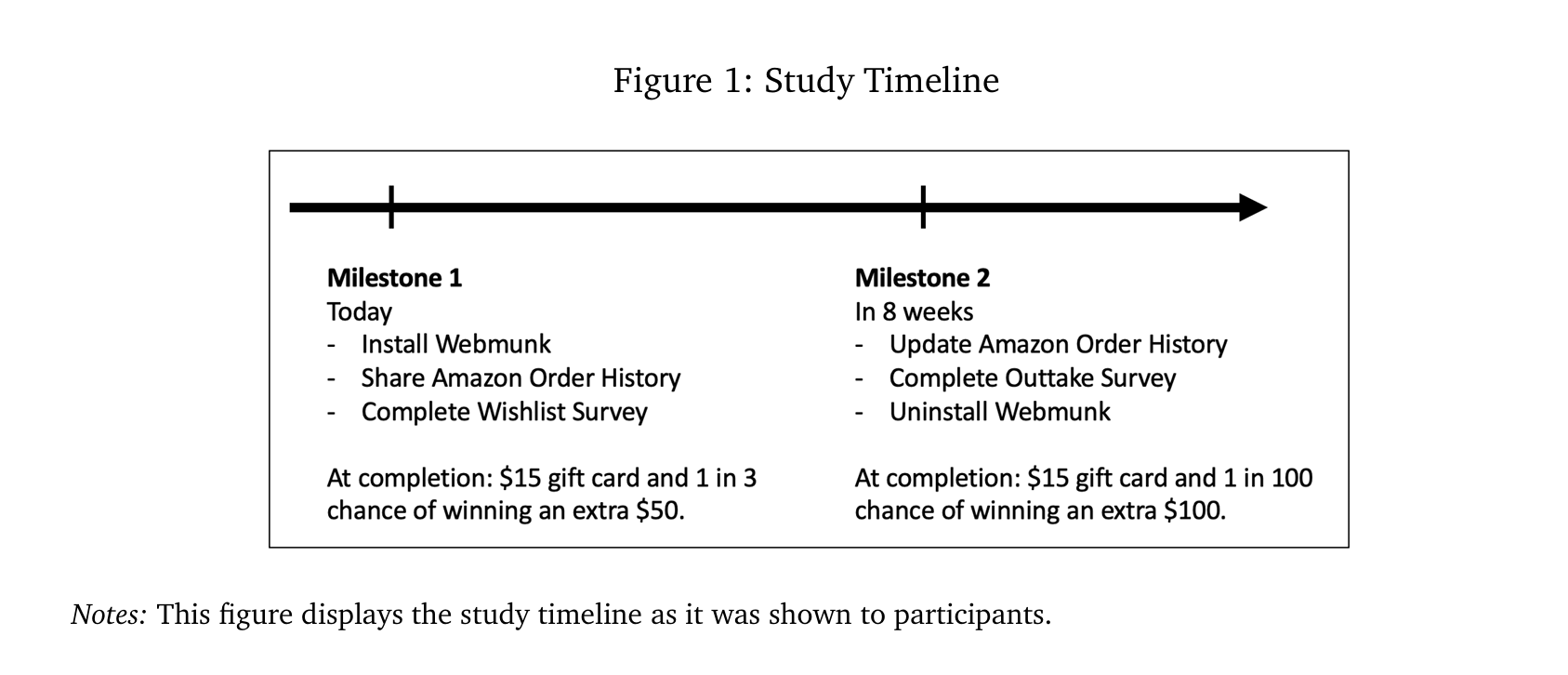

Recruitment and Study Timeline. We recruited American adults through Facebook advertise ments between mid-June and the beginning of October 2023.8 Participants filled out an initial Qualtrics survey, which determined eligibility for the study and collected explicit participant consent to be part of the study. The survey is available in Appendix D. Three eligibility criteria are worth highlighting. First, participants must shop online primarily on a computer, given that Webmunk cannot be installed on a mobile phone or tablet. In our case, over half of the partic ipants satisfy this condition. Second, participants must use Chrome for their regular browsing, because Webmunk only works on Chrome. This is not a big constraint, since roughly three quar ters of the respondents who shop on a computer use Chrome. Third, participants need to be frequent Amazon shoppers (shop at least 2 to 3 times a month on Amazon).

Click to read more