Abstract

Most online marketplaces are peer-to-peer. Credit ones, however, are not and they have resurrected many features of traditional financial intermediaries. To understand why, we use online credit as a laboratory to investigate the value of financial intermediation. We develop a structural model of online debt crowdfunding and estimate it on a novel database. We find that abandoning the peer-to-peer paradigm raises lender surplus, platform profits, and credit provision, but exposes investors to liquidity risk. A counterfactual where the platform resembles a bank by bearing liquidity risk can generate larger lender surplus and credit provision when liquidity is low and lenders are risk averse.

1. Introduction

Third, our paper contributes to the literature on structural estimation in financial intermediation (Egan et al., 2017, Crawford et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2022), online credit (Kawai et al., 2022, Xin, 2020, Tang, 2020, DeFusco et al., 2022), and online marketplaces in general (Dinerstein et al., 2018, Einav et al., 2018, Fréchette et al., 2019, Farronato and Fradkin, 2022). Work in this literature has so far focused on buyers and sellers or lenders and borrowers, placing less emphasis on an active role for platforms. In contrast, our approach directly models the design of portfolio products by the platform.

2. Institutional background, data, and descriptive evidence

2.1. Development of the business model of online debt crowdfunding

Online debt crowdfunding in China experienced a similar evolution despite recently undergoing a restructuring driven by regulation. A number of platforms have shut down, and others have become “loan aid agencies” selling services to traditional intermediaries. However, several Chinese platforms that continue to operate offer bank-like products. For instance, in 2019 FinVolution (formerly Paipaidai) acquired a 4.99% stake in Fujian Strait Bank and formed an alliance with the bank focused on consumer lending, and 9fgroup Tech invested in Hubei Consumer Finance Company through its wholly-owned subsidiary; in 2023, Lufax Holding announced its acquisition of Ping An OneConnect Bank (Hong Kong) Limited.2 Despite the regulatory tightening, Chinese online credit companies continue to pursue bank-like activities through alliances, acquisitions, and by shifting their focus to Hong Kong.

2.2. Renrendai

We base our analysis on a novel, hand-collected database covering the universe of loan applications and credit outcomes on debt crowdfunding platform Renrendai (人人贷). During our sample period, Renrendai was the fifth largest player in the sector in China, and as of 2019 it had a 5% market share.3 Between its launch in 2010 and the end of our sample period in February 2017, Renrendai had a cumulative turnover of ¥25 bn ($3.7 bn) and registered over 1 million active users between borrower and lender accounts.

During our sample period, Renrendai is representative of a typical debt crowdfunding platform as it operates like most online credit platforms in China as well as other countries. In Renrendai, users can be borrowers or lenders. Borrowers pay a small participation fee to apply for a loan on the platform.4 When submitting a loan application, a prospective borrower specifies the amount she seeks, and proposes an interest rate and maturity. Renrendai pre-screens loan applications, assigning a credit rating to borrowers. Following this step, loan applications become visible to prospective lenders, and are available on Renrendai’s platform for one week. If an application is not fully funded within that time window, it is considered unsuccessful and it is turned down; Renrendai then removes the application from its website and the borrower does not receive the funds she requested.

Lenders pay no fees and can invest on Renrendai via two channels: direct (peer-to-peer) credit, where the lender selects the individual loans she intends to fund, and marketplace credit, where the platform sells the lender a share in a diversified portfolio of loans. Marketplace lenders can choose from a menu of portfolios known as Uplan (Uu计划). Renrendai offers every day a new set of Uplan portfolios, differentiated by target annual return (ranging between 6% and 11%), maturity (between 3 and 24 months), and minimum investment amount (¥1000 or ¥10,000). At maturity, Uplan lenders can roll their investment over or liquidate it. If they liquidate, the platform places the underlying loans on the secondary market, and does not bear the liquidity risk: the lenders do not receive a payment until all the corresponding loans have been resold. The loan is sold “at par”, i.e., at a fixed price of ¥1 for each ¥ loaned. As the price does not adjust to market conditions, the seller may not be able to find immediately a buyer and might be forced to wait before disposing of the loan. Renrendai makes a profit on Uplan based on the spread between the interest payments it receives on the underlying loans and the returns it pays to the lenders.

Fig. 1 breaks down credit at Renrendai during our sample period between direct and marketplace loans. When Renrendai was first launched, online debt crowdfunding was based on the older peer-to-peer paradigm, and 100% of loans were direct. Portfolio investment was introduced in December 2012, and since then we observe a steady rise of marketplace credit, reaching 98% of total investment at the end of our sample period in February 2017. We build on this stylized fact, and investigate the welfare effects of the marketplace credit model in comparison to alternative platform designs. In October 2020, regulatory pressure to limit online lending led to withdrawals and low liquidity in Renrendai’s secondary market. Since this happened more than three years after our sample period, it is unlikely that loans from before March 2017 are the root of these developments.5

Fig. 1. Direct and marketplace loans at Renrendai, 2010Q4–2017Q1.

The figure plots the outstanding volumes of loans at Renrendai, for each calendar quarter over the period 2010–2017. The dark bars denote direct, or peer-to-peer, loans, and the lighter-shaded bars loans that are part of portfolio products, i.e., marketplace loans.

2.3. Data; loan applications, funded loans, and portfolio products

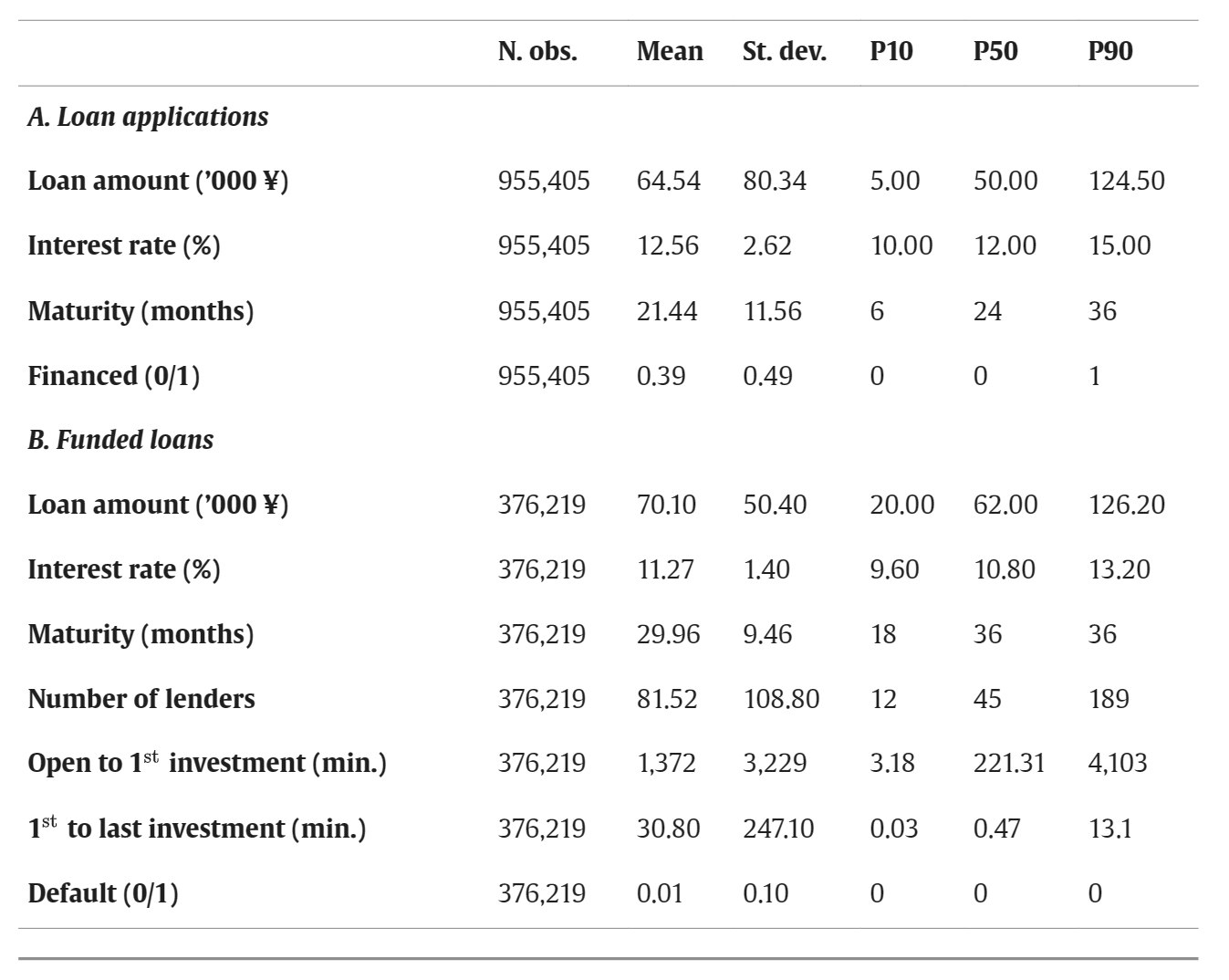

Table 1. Summary statistics, loans.

The table reports summary statistics for loan applications (panel A) and funded loans (panel B) on Renrendai, over the period 2010–2017. One observation corresponds to a loan. All variables are defined in detail in Appendix A.

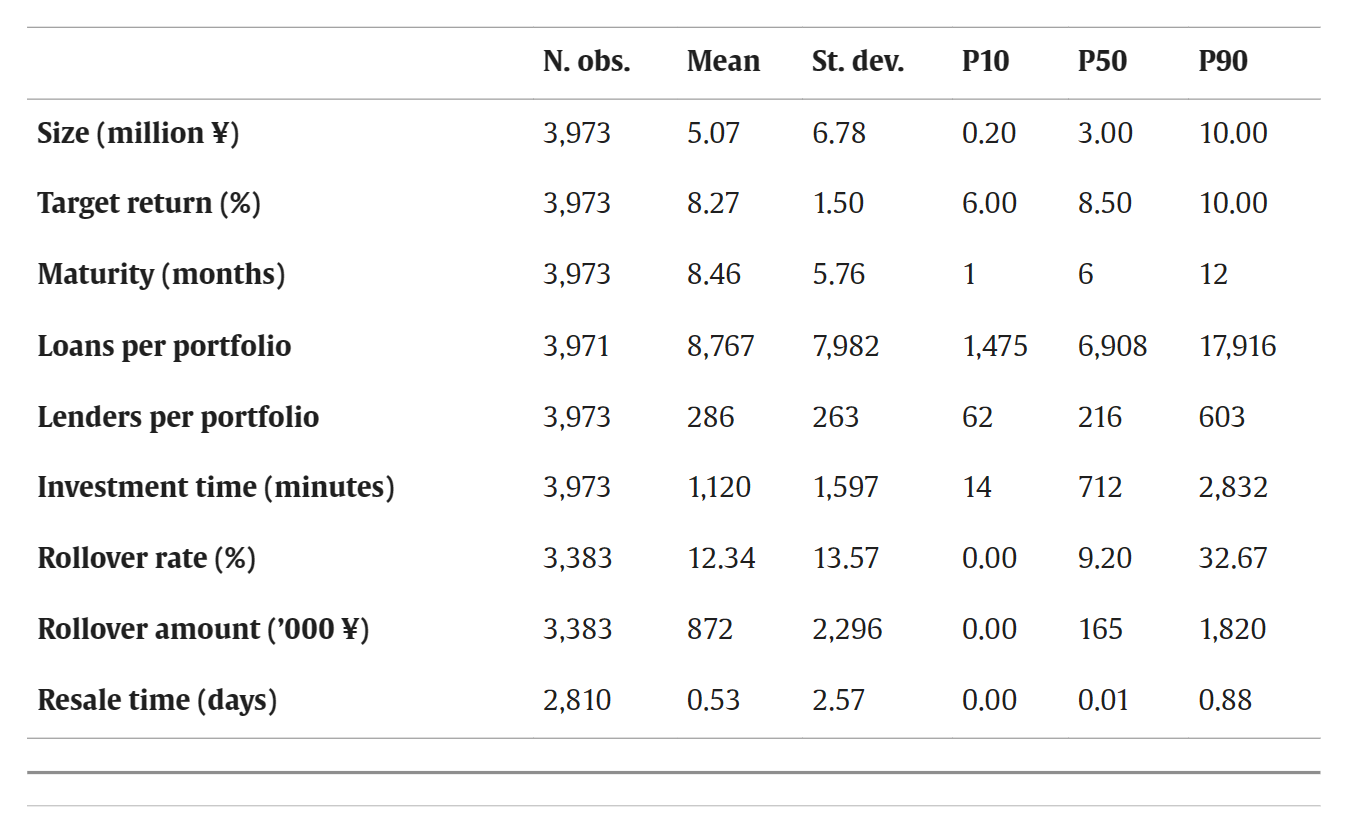

Table 2. Summary statistics, portfolio products.

Fig. 2. Maturity mismatch on Renrendai’s portfolio products.

The figure plots the outstanding amounts of portfolio products sold by Renrendai and their underlying loans by maturity bins. The light bars represent the total outstanding amounts of portfolio products. The dark bars represent the total amount of outstanding loans underlying the portfolio products.

2.4. Borrowers and lenders; maturity mismatch and liquidity risk

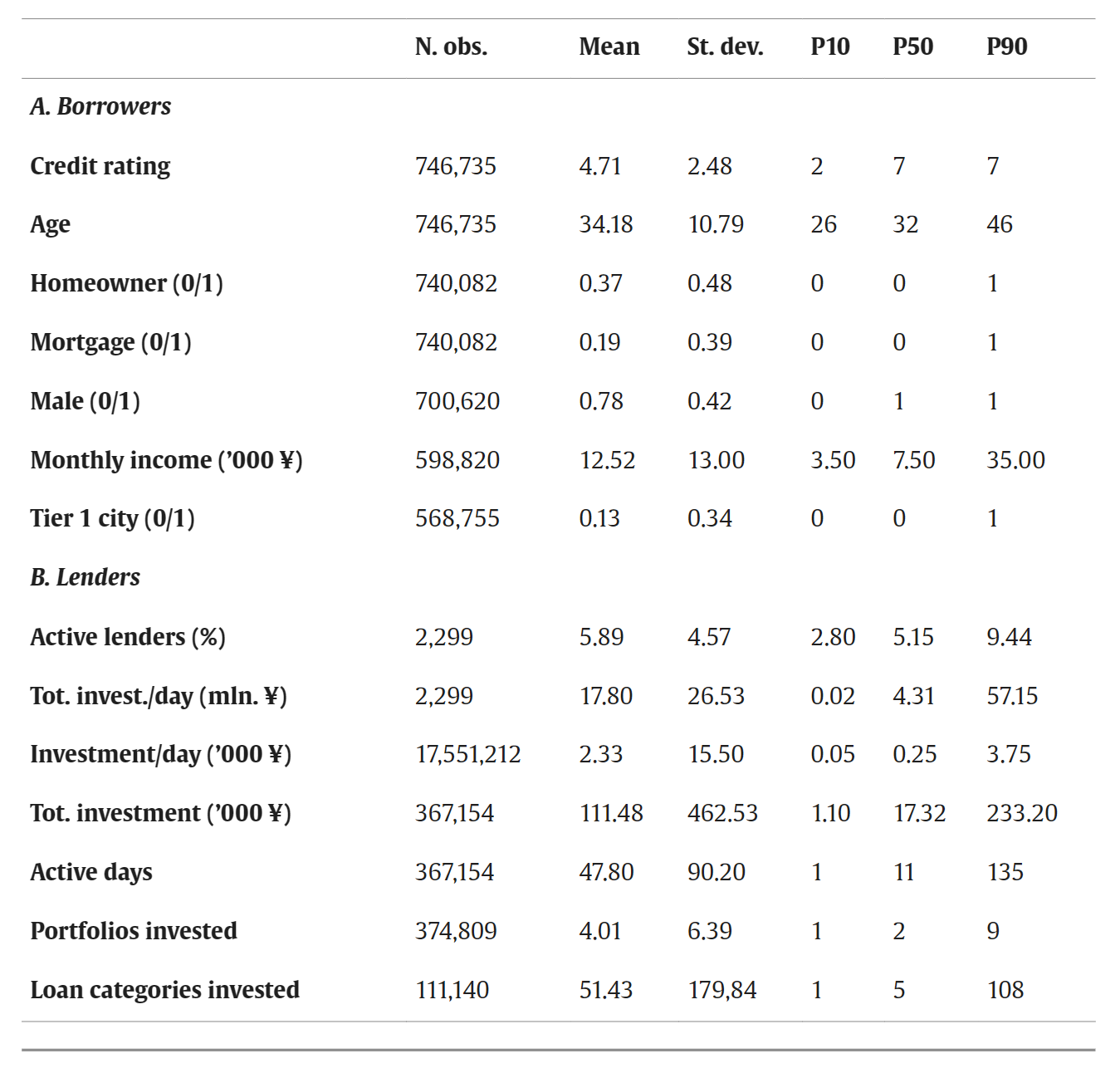

Table 3. Summary statistics, borrowers and lenders.

To capture those changes and reflect the increased investor heterogeneity, we focus on the percentage of active lenders on the platform on a given day. We define a lender as active if she is in the top 5% of the distribution of platform use, defined as the number of times she invested up to that date.7 This variable reflects familiarity with the platform and/or laxer financial constraints: because Renrendai requires a minimum investment amount, more frequent investments indicate that the lender has greater financial resources, and should therefore be less liquidity risk-averse. We compute the daily share of active investors as the ratio of active investors to the total number of lenders investing on the platform on a given day. Descriptives for this variable are reported in Table 3.

3. Model

Our model features three players: borrowers, lenders, and a debt crowdfunding platform. Appendix Figure D.1 provides a graphical summary of the model.

3.1. Borrowers