We propose a new perspective on family firms' puzzling under-diversification in product spaces: these firms first need to succeed in exploratory innovation so they may diversify into new product markets. We construct a large database of family ownership and patent records of U.S. public firms, and show that family firms produce more exploratory patents than others, a relation that is stronger among under-diversified family firms. In addition, we find that such innovation indeed helps family firms diversify business risks. A causal interpretation of our result is supported by (i) using the property division standard in state-level divorce laws as an instrumental variable and (ii) constructing a propensity score matched sample. This effect is also more pronounced among larger firms, older firms, and firms in industries with faster technology replacement. Our empirical evidence addresses family firms' under-diversification puzzle through the lens of innovation strategies.

1. Introduction

Family firms have played an important role in the global economy.

1 Unlike typical publicly listed firms, risk diversification presents a key consideration for family firms, as retaining control requires controlling families' wealth and attention concentrated in a single firm (e.g.,

Faccio and Lang, 2002;

Shleifer and Vishny, 1992). Moreover, controlling families have a long-horizon perspective (

Kim et al., 2008;

Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2005), motivating them to pursue diversification when they identify long-term risks and challenges to their current business (

Choo et al., 2009;

Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007,

Gomez-Mejia et al., 2010). Given the importance and practicality of risk diversification, it is puzzling that family firms often remain under-diversified in product spaces (

Anderson and Reeb, 2003;

Feldman et al., 2016;

Gomez-Mejia et al., 2010).

In this paper, we revisit this puzzle by investigating how diversification influences family firms' development of technologies prior to product creation. As technology cycles accelerate and innovation competition intensifies, firms and managers must invest in R&D and innovative activities to survive and thrive in the long run (

Ahuja et al., 2008;

Sundaram et al., 1996). This persistent pressure may compel family firms to more actively pursue new technologies aligning with their long-term perspective (

Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). We hypothesize that the diversification incentives of controlling families may prompt their firms to particularly favor

exploratory innovation. Exploratory innovation generates new knowledge that is substantively different from a firm's existing expertise through distant searches, radical experimentation, and revolutionary approaches (

March, 1991;

Levinthal and March, 1993). This enables firms to expand into new technological domains and unrelated business fields (

Kim et al., 2024;

Lavie et al., 2010). Consequently, exploratory innovation serves as the

first step for controlling families to diversify their concentrated business risks.

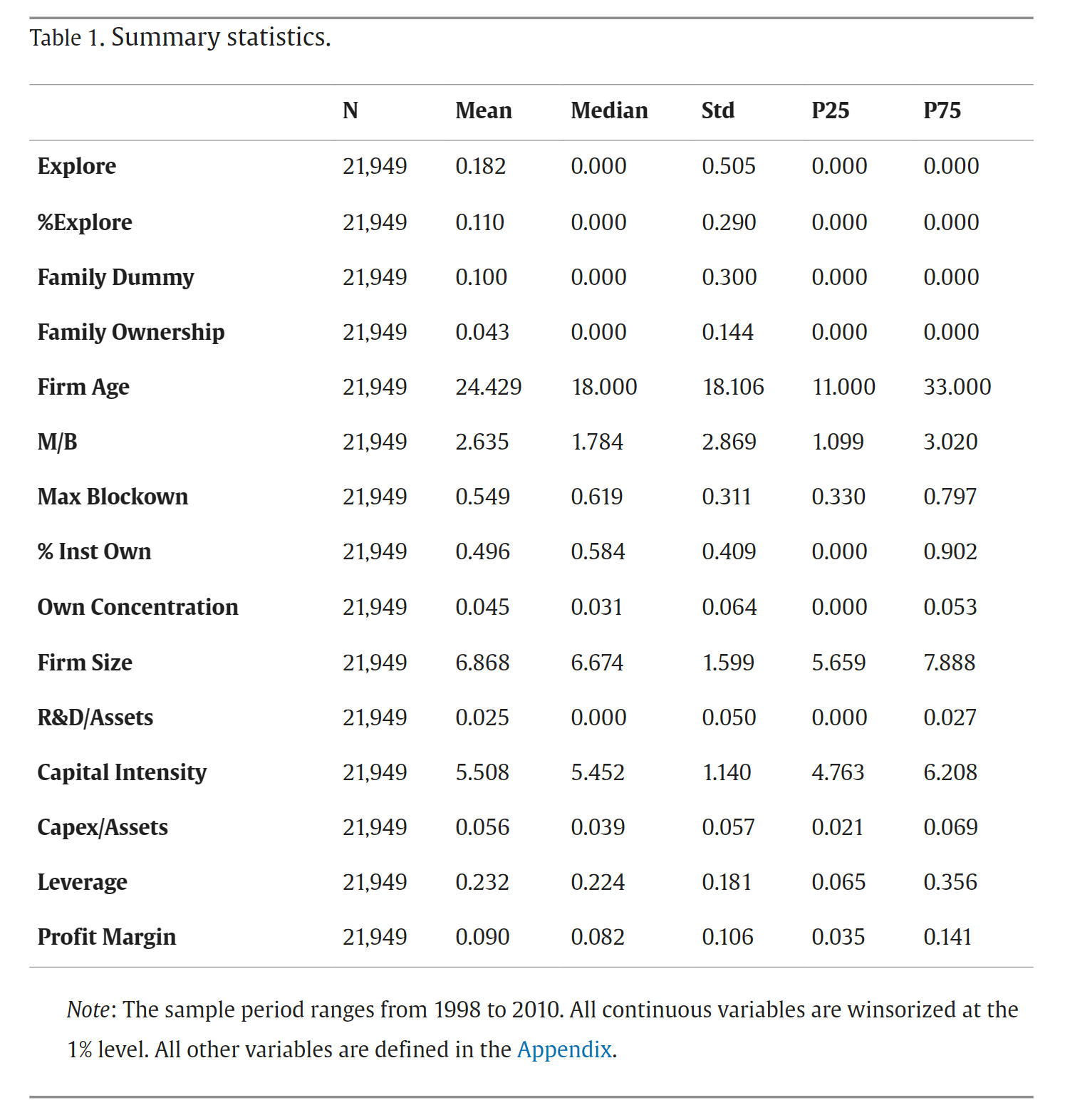

To empirically examine our proposition, we construct a large database of family ownership of 3,391 U.S. public firms and link it to U.S. patent data, which sets our study apart from prior research that has focused on a smaller, selected sample or on index firms such as Fortune 100 or S&P 500. We define a patent as exploratory if it has a higher ratio of backward citations to prior patents that are outside of the filing firm's existing knowledge base. We regress a firm's number or ratio of exploratory patents filed in a year on the firm's family ownership (measured by a family-firm indicator variable or a ratio of family ownership in total shares), controlling for several firm characteristics, year fixed effects, and industry fixed effects. Our results suggest that family ownership is positively related not only to the number of exploratory patents but also to the ratio of exploratory patents in a firm's new patent portfolio. This relation is not only statistically significant but also economically sizable: when a nonfamily firm becomes family-owned, its number (ratio) of exploratory patents will increase by 37.2% (8.5%). In addition, a one-standard-deviation increase in family ownership is associated with an 8.0% increase in the filing of exploratory patents.

We further validate the diversification motive underlying the above relation. If the purpose of adopting exploratory innovation is to reduce risks, then less-diversified family firms should be more inclined to adopt exploratory innovation. This is supported in the data. We regress a firm's number or ratio of exploratory patents on the interaction term between an indicator for single-sector firms and the firm's family ownership. On the one hand, the significantly negative coefficients on the single-sector indicator suggest that firms with concentrated product lines are less likely to pursue exploratory innovation. On the other hand, the insignificant coefficients on family ownership suggest that family firms do not always pursue exploratory innovation. More importantly, the coefficients on the interaction term are significantly positive, confirming that only less-diversified family firms have the incentive to file exploratory patents.

Moreover, exploratory innovation should contribute to the intended outcomes of risk diversification, such as reduced volatility in profitability and stock returns. Our tests confirm this prediction: we find lower volatility in return on assets (ROA) and stock returns among firms filing at least one exploratory patent. Taken together, these findings support our hypothesis that family firms engage in exploratory innovation to achieve diversification, thereby mitigating risks to the monetary and socioemotional wealth of controlling families.

A general concern of our baseline analysis is that the family ownership-exploratory innovation relation may not be causal. For instance, confounding factors that influence both family ownership and innovation strategies could exist. To mitigate such endogeneity concerns, we consider the property division standard in state-level divorce laws as an instrumental variable.

2 State divorce laws based on the community property standard benefit the poorer spouse (

Voena, 2015) and thus can negatively affect the incentives for the wealthier spouse to accumulate family assets (e.g.,

Dnes, 1998;

Voena, 2015;

Fischer and Khorunzhina, 2019;

Frémeaux and Leturcq, 2022). Theses property division standards are also plausibly exogenous to firm fundamentals (

Roussanov and Savor, 2014). As such, state divorce laws help identify variations in family ownership. Consistent with its known negative impact on family assets, we observe that the community property standard negatively affects family ownership. More importantly, instrumented family ownership that is free of confounding effects still positively explains exploratory innovation output in the second stage, which supports a causal interpretation.

We also construct a propensity score matched sample in which family and nonfamily firms are homogenous in all firm characteristics using propensity score matching (

Villalonga, 2004;

Feldman et al., 2016). This sample mitigates the concern that family-owned firms might be different from nonfamily firms in terms of characteristics that are spuriously correlated with exploratory innovation. Also in this case, we observe a consistent, positive relation between family ownership and exploratory innovation.

We also examine the heterogeneous effects on the incentives of family firms to expand business opportunities. We first document that larger family firms are more exploratory than smaller ones in innovation activities. This observation is reasonable because family firms are more subject to financial constraints due to controlling families' need to retain control and reluctancy in seeking external capital (

Morck et al., 2000;

Morck and Yeung, 2003;

Munari et al., 2010). Thus, larger family firms face fewer financial constraints when pursuing exploratory innovation (

Xiang et al., 2019;

Eng et al., 2021).

Next, we observe that older family firms tend to pursue more exploratory innovation. Two economic reasons may help explain this observation. First, older firms are more likely to rely on obsolete technologies, which gives them a stronger incentive to engage in exploratory innovation to ensure their long-term survival and technological diversification (

Grandstrand, 1998). This incentive is likely stronger for family firms, which have longer investment horizons and require renewal through innovation to avoid failure (

Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011;

Laforet, 2013). Second, older firms tend to be controlled by later generation-families. These families have a greater incentive to preserve the value of their inherited assets, and see risk diversification as an important tool to achieve this goal. This effect aligns with recent findings that the second-generation successors tend to shift innovation trajectory toward exploration in China and Turkey (

Erdoğmuş et al., 2017;

Carney et al., 2019).

Lastly, we consider the effect of technology obsolescence. We find that the relation between family ownership and exploratory innovation is stronger in more R&D-intensive industries and industries with shorter half-life of backward citations, respectively. These results suggest that exploratory innovation matters more for family firms operating in industries characterized by more rapid technological changes. They are also consistent with our proposition because controlling families of high-tech firms should also prioritize innovation when technological changes accelerate (e.g.,

Sundaram et al., 1996;

Trembley and Chênevert, 2008).

Our study is related to several strands of the literature. First, we provide a new perspective on the family ownership and diversification relation. Our findings on family firms pursuing exploratory innovation and technological diversification reconcile the puzzling contrast between the theoretical prediction of family firms' higher diversification and counter evidence from prior empirical analyses (

Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011, pp. 667–668). Our evidence also echoes the proposition of

Ahuja and Novelli (2017) that firms can be relatedly diversified in technologies but not in product markets. Moreover, our analyses for the boundary conditions including firm size, firm age, and technology pace offer additional insights on this literature.

Second, we provide new evidence to the literature on the determinants of exploratory innovation. Prior studies have examined how exploratory innovation is influenced by managerial capabilities (

Levinthal and March, 1993;

Smith and Tushman, 2005), alliances and networks (

Phelps, 2010;

Rothaermel and Deeds, 2004;

Yang et al., 2014), mergers and acquisitions (

Stettner and Lavie, 2014), and business environments (

Kim et al., 2024;

McGrath, 2001).

3 Our empirical evidence for the effect of family ownership fills a gap in the literature of exploratory innovation (

Brinkerink, 2018;

Ardito and Capolupo, 2024).

Finally, our study also adds to the literature on the role that family ownership plays with respect to corporate innovation. Our proposition and empirical evidence suggest that major shareholders' diversification considerations could also fundamentally shape a firm's innovation choices. While some studies find that family firms are more engaged in innovation (e.g.,

Choo et al., 2009;

Duran et al., 2016;

Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2005;

Schmid et al., 2014), other studies point to the opposite direction (

Morck et al., 2000;

Morck and Yeung, 2003;

Munari et al., 2010). In contrast to these studies and their focus on the level of innovation, we focus on the

direction of innovation (i.e., exploratory innovation) that is closely related to firms' technological diversification and subsequent product diversification.